If you drive over the Santa Maria River California on Highway 101, you'll probably just see a massive, sandy wasteland. It looks dead. Honestly, most tourists heading toward Pismo Beach don't even realize they've crossed a river at all. But don't let the dry riverbed fool you; what's happening underneath that sand is the lifeblood of one of the most productive agricultural valleys on the planet.

It’s a weird river. Truly.

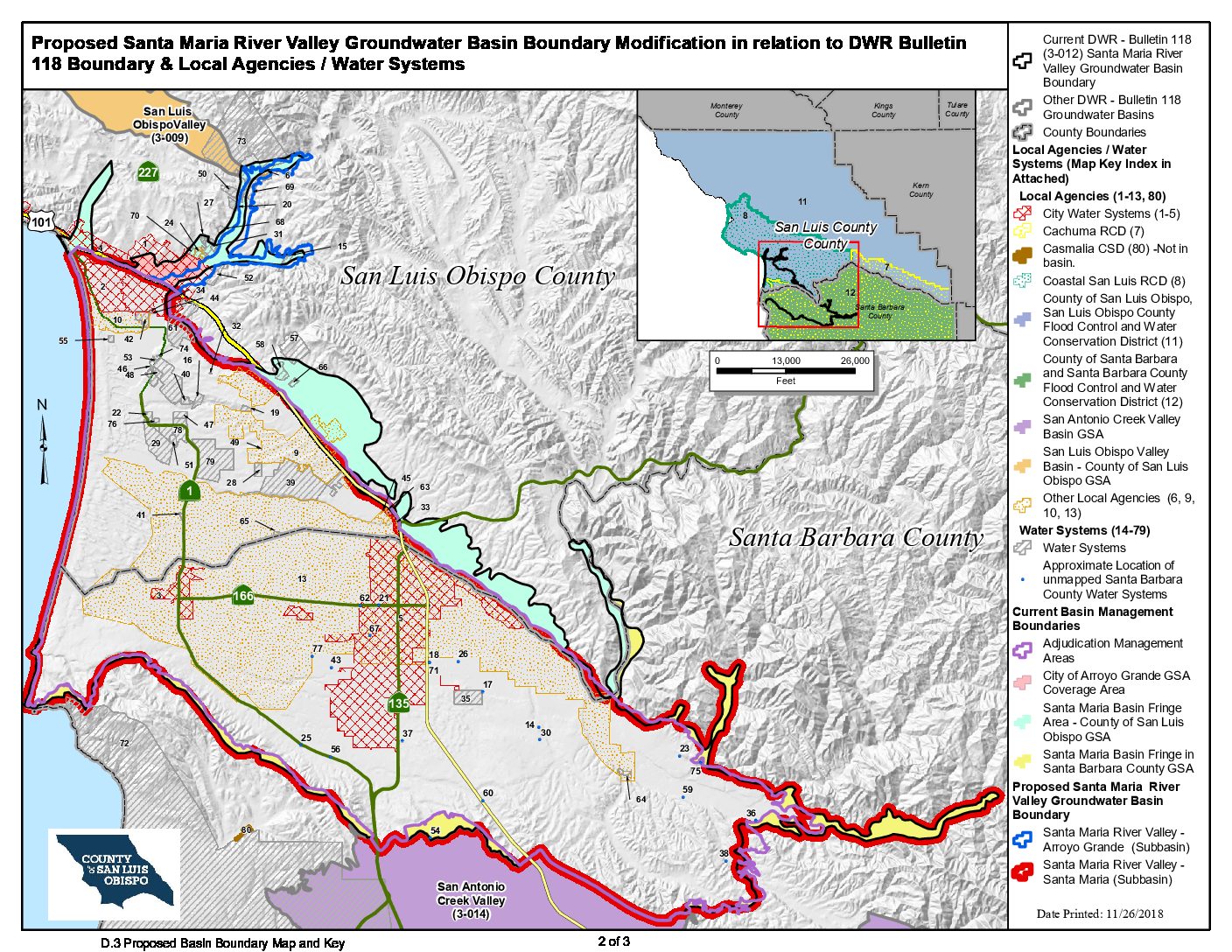

Most rivers flow on top of the ground. The Santa Maria River prefers to stay hidden. Formed by the convergence of the Cuyama and Sisquoc rivers, it defines the boundary between San Luis Obispo and Santa Barbara counties. It’s roughly 24 miles long, but for a huge chunk of the year, it’s basically a ghost. You see a dry wash, but the farmers in the Santa Maria Valley see a massive underground reservoir that keeps their strawberries and broccoli alive when the rest of the state is parched.

The Myth of the Dry Riverbed

People think "dry" means "empty." That is a huge mistake.

The Santa Maria River California is essentially an "influent" stream. This is a fancy geological way of saying the water drains into the ground rather than just sitting on top of it. Because the soil here is so porous and sandy, the water drops straight down into the Santa Maria Valley Groundwater Basin.

Think of it like a giant sponge.

When we get those massive atmospheric rivers hitting the Central Coast, the transformation is violent. I’ve seen it go from a playground for dirt bikes to a raging, chocolate-colored torrent in a matter of hours. In the 1969 floods, this "dry" river was moving so much water it threatened to take out bridge infrastructure. It’s a boom-or-bust system.

The Sisquoc River, which feeds into it, is one of the last "wild" rivers in Southern California. It hasn't been dammed into oblivion. Because it remains relatively untouched in its upper reaches, it brings down a specific type of sediment and nutrient load that makes the valley floor incredibly fertile.

🔗 Read more: Why Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station is Much Weirder Than You Think

Agriculture and the Tug-of-War for Water

You can't talk about this river without talking about money. Specifically, strawberry money.

The Santa Maria Valley is world-famous for its berries. If you’ve eaten a strawberry in a New York grocery store in June, there’s a statistically high chance it came from within ten miles of this river. But that productivity requires an insane amount of water.

For decades, there has been a complex legal and environmental struggle over who gets the water. On one side, you have the Twitchell Dam. Built in the late 1950s by the Bureau of Reclamation, this dam doesn't actually hold water for "storage" in the traditional sense. Its primary job is "recharge." It catches the winter runoff from the Cuyama River and then slowly releases it so it can soak into the Santa Maria River California riverbed.

It's a slow-motion delivery system for the aquifers.

The Steelhead Dilemma

But there’s a catch.

The Southern California Steelhead is an endangered species. Historically, these fish would wait for the winter rains, swim up the Santa Maria River, and head into the Sisquoc to spawn. Because we now capture that water at Twitchell Dam to save it for farmers, the river doesn't always flow long enough or deep enough for the fish to make the trip.

Environmental groups have been locked in a decades-long battle with the Santa Maria Valley Water Conservation District. They want more water released to help the fish. Farmers want that water kept in the ground for the crops. It’s a classic California standoff where nobody is really the "villain"—it’s just a fight over a finite resource in a semi-arid climate.

💡 You might also like: Weather San Diego 92111: Why It’s Kinda Different From the Rest of the City

Where to Actually See the Water

If you want to actually experience the Santa Maria River California without staring at a dry ditch, you have to go to the mouth.

The Guadalupe-Nipomo Dunes are where the river finally meets the Pacific Ocean. This is a spectacular, rugged landscape. It's also where Cecil B. DeMille filmed The Ten Commandments in 1923 and then literally buried the set in the sand because it was too expensive to move.

At the Rancho Guadalupe Dunes Preserve, the river often forms an estuary. This is bird-watching heaven. You’ll see:

- Western Snowy Plovers (they are tiny and very protected)

- California Least Terns

- Brown Pelicans

- Great Blue Herons

The estuary is a transition zone. It’s where the saltwater of the Pacific pushes back against the freshwater of the river. Even when the river isn't flowing at the 101 bridge, there’s often water pooling here at the coast. It’s a hauntingly beautiful place where the wind is almost always howling, and the sand shifts so fast it can bury a fence line in a week.

The "Invisible" Infrastructure

One thing people get wrong about the Santa Maria River is thinking it's a natural, untouched system. It isn't. Not by a long shot.

The river is heavily managed. There are levees designed to keep the water from reclaiming the city of Santa Maria. There are "percolation ponds." There are complex pumping stations.

The US Army Corps of Engineers is constantly monitoring the "project" reaches of the river. If the river were allowed to wander where it wanted, the entire economic engine of the valley would be at risk. But by pinning the river down, we’ve changed how it functions. It no longer meanders across the plain, which means the natural "cleaning" process of a flood plain is somewhat stifled.

📖 Related: Weather Las Vegas NV Monthly: What Most People Get Wrong About the Desert Heat

Is it worth a visit?

Honestly, if you're looking for a place to kayak or swim, the Santa Maria River California is going to disappoint you 350 days out of the year. It’s not the Russian River or the Sacramento River.

However, if you are into geology, birding, or the "hidden" side of California’s food system, it’s fascinating.

The best way to see it is to start at the Sisquoc River trailheads in the Los Padres National Forest. Hike through the San Rafael Wilderness. You’ll see the water in its purest form—crystal clear, cold, and running over white rocks. Then, drive down into the valley and see that same water being pulled out of the ground by massive diesel pumps to grow your salad.

It’s a stark reminder of how we’ve bent nature to our will in California.

Surprising Facts Most People Miss

- The Sand Mining: For years, the riverbed was a source of high-quality construction sand.

- The Mercury Issue: Like many California rivers, there have been historical concerns about mercury runoff from old mining sites in the mountains, though the Santa Maria is generally cleaner than rivers further north in the Gold Country.

- The Saltwater Intrusion: Because we pump so much water out of the ground near the river, there is a constant fear that the ocean will start "sucking" salt water back into the freshwater aquifer. This would be a "game over" scenario for the strawberry industry.

What You Should Do Next

If you want to understand the Santa Maria River California, don't just look at it from the highway.

First, check the USGS flow gauges online before you go. If the flow at the Guadalupe gauge is anything above zero, go to the Rancho Guadalupe Dunes Preserve. It is one of the few places in the state where you can see a river mouth that feels truly wild.

Second, visit the Oso Flaco Lake area just north of the river mouth. While technically a separate drainage, it’s part of the same dune complex and gives you a much better sense of what this coastline looked like before it was turned into a grid of lettuce fields.

Third, support the local farm stands. When you eat a Santa Maria strawberry, you are essentially eating the recycled snowmelt of the Sierra Madre mountains that traveled through the Santa Maria River's underground "pipe" system.

Understanding this river requires looking past the surface. It is a workhorse, not a showpiece. It's a complex, litigious, hidden, and vital artery that keeps the Central Coast alive.