You’re driving toward Palm Springs, the AC is humming, and suddenly the car starts shaking. It isn't your alignment. It’s the wind. That brutal, unrelenting gale that whips through the San Gorgonio Pass California is more than just a nuisance for commuters; it is one of the most geographically significant "choke points" in the entire United States. Most people just see the white windmills and keep driving. They miss the fact that they are crossing a geological bridge between two massive mountain ranges—the San Bernardino and the San Jacinto—that literally dictates the weather for millions of people in the Inland Empire.

It's windy. Really windy.

Geologically, the San Gorgonio Pass is a "gap" created by the San Andreas Fault. While most mountain passes are high-altitude notches you have to climb over, this one is a low-elevation floor that sits at about 2,600 feet. It is one of only three major passes in Southern California, along with the Cajon and Tejon. Because it’s so low, it acts like a giant funnel. High pressure from the coast tries to squeeze through this narrow gap to reach the low-pressure desert on the other side. The result? Venturi effect. The air speeds up, creates those famous gusts, and powers one of the oldest and largest wind farms in the country.

Why the San Gorgonio Pass California Actually Matters

If you look at a map, the pass is basically a 15-mile long stretch between Banning and Whitewater. It’s the primary gateway for the I-10 freeway. If this pass shuts down—which it does during major fires or severe wind storms—Southern California’s logistics basically break.

The history here isn't just about dirt and rocks. It’s about survival. For the Cahuilla people, this was a vital corridor long before Spanish explorers or American pioneers showed up. They knew how to navigate the transition from the lush, Mediterranean climate of the west to the harsh, arid Colorado Desert to the east. Honestly, the shift in vegetation is wild. You can be looking at pine trees in the distance and, within five minutes of driving east, you're surrounded by creosote and sand.

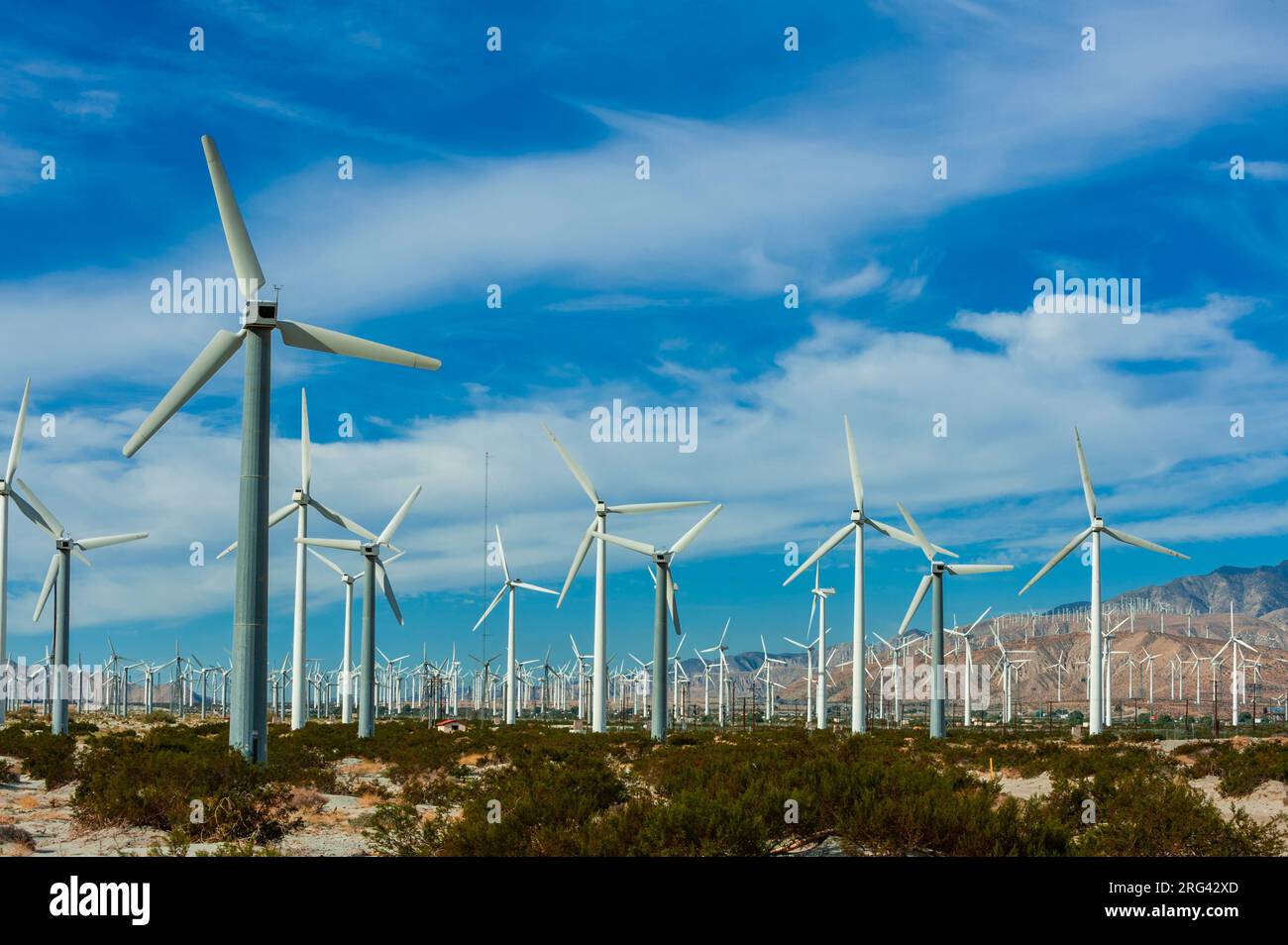

The Wind Farm Phenomenon

You’ve seen them. Thousands of white turbines spinning (or sometimes sitting perfectly still). People often ask why some aren't moving when it's clearly windy. Usually, it's because the grid is full or a specific turbine is undergoing maintenance. The San Gorgonio Pass wind farm began in the 1980s. It was a massive experiment. Back then, the technology was hit-or-miss, and the pass became a graveyard for "failed" turbine designs. Today, the tech is far more efficient.

👉 See also: Red Hook Hudson Valley: Why People Are Actually Moving Here (And What They Miss)

- Turbine Count: At its peak, there were over 4,000 turbines.

- Power Output: They generate enough juice to power nearly the entire Coachella Valley.

- Height: Modern turbines are significantly taller than the "legacy" models from the 80s, reaching heights that rival skyscrapers.

Living in the pass—places like Cabazon or Banning—means dealing with "Sandblast Sundays." When the Santa Ana winds kick up, the visibility drops to zero. It isn't just dust; it’s actual grit that can take the paint right off your car if you’re not careful. Locals know to check the "Wind Advisory" signs before towing a high-profile trailer. If the wind is hitting 60 mph, those trailers turn into kites.

The San Andreas Elephant in the Room

We have to talk about the fault. The San Andreas Fault runs right through the heart of the San Gorgonio Pass California. This is actually one of the most complex parts of the entire fault system. In most places, the fault is a clean line. Here, it gets "knotted." The Pacific Plate and the North American Plate are basically grinding against each other in a way that creates a massive amount of tectonic pressure.

Geologists from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) have studied this area for decades because it’s a "seismic gate." There is a legitimate debate among scientists about whether a massive earthquake starting in the Salton Sea could "jump" through the pass and head toward Los Angeles. Some researchers, like Dr. Lucy Jones, have highlighted how the complex geometry of the faults in the pass might actually slow down or stop a rupture. Others aren't so sure. It’s a literal ticking time bomb, but it’s also the reason we have such dramatic mountain scenery.

Without the fault, there is no pass. The mountains are being pushed up while the valley floor stays relatively low. It’s a beautiful, violent mess of geology.

Hidden Gems You Usually Drive Past

Most people stop at the Hadley Fruit Orchards for a date shake or hit the Desert Hills Premium Outlets. Those are fine, but they aren't the real pass experience.

✨ Don't miss: Physical Features of the Middle East Map: Why They Define Everything

- Mormon Rocks: Technically a bit further toward Cajon, but the rock formations leading into the pass area are stunning.

- Whitewater Preserve: Just off the freeway, this is a literal oasis. You can walk through a desert riparian habitat where the Whitewater River actually flows year-round (mostly). It’s a jarring contrast to the dry wind turbines just a mile away.

- The Pacific Crest Trail (PCT): The trail actually crosses under the I-10 near the pass. Hikers who have walked all the way from Mexico often find this section one of the most grueling because of the heat and the wind.

If you’re a birder, the pass is a major migratory corridor. Because the mountains are so high on either side, birds are forced through the gap. During the spring and fall, you can see hawks, eagles, and thousands of smaller songbirds navigating the same wind currents that the turbines use.

The Logistics of the Pass: A National Artery

Let’s talk about the Union Pacific railroad. If you sit at a rest stop in the pass, you’ll see trains that seem to never end. This is the "Sunset Route." It connects the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach to the rest of the country.

The grade here is steep enough that heavy freight trains often need "helper" engines to push them up the incline from the desert side. It’s a massive logistical dance. When a train breaks down in the pass, it ripples across the national supply chain. We’re talking about billions of dollars in goods moving through this narrow strip of land every single week.

Weather Is the Real Boss

The "marine layer" is a common sight in the pass. You’ll see a wall of white clouds trying to push through from the Beaumont side toward the desert. Usually, the heat of the desert "eats" the clouds. You can literally watch the fog evaporate as it hits the dry air of the pass.

It’s also one of the few places in the world where you can experience a 40-degree temperature swing in about twenty minutes. You leave the 70-degree coastal breeze in Redlands, climb into the pass, and by the time you hit the descent into Palm Springs, it’s 110 degrees. That thermal gradient is what drives the wind. The hotter the desert, the harder the wind blows through the pass to fill the void.

🔗 Read more: Philly to DC Amtrak: What Most People Get Wrong About the Northeast Corridor

Misconceptions About the Area

A lot of people think the San Gorgonio Pass California is just a "pass-through" area with no culture. That’s wrong. Banning and Beaumont have deep roots in the California apple and cherry industries. The "Stagecoach Days" in Banning aren't just a kitschy festival; they're a nod to the fact that this was the only way to get mail and people into the interior of the state in the 1800s.

People also assume the windmills are a bird-killing machine. While older designs were problematic, newer turbines spin slower and are placed more strategically. Organizations like the Audubon Society have worked with energy companies to mitigate the impact. Is it perfect? No. But it's much better than it was thirty years ago.

What You Should Actually Do Next Time You're Here

Stop. Don't just floor it to get to the casinos or the Coachella festival.

Take the exit for Whitewater. Drive the few miles back into the canyon. The air temperature drops, the sound of the freeway vanishes, and you realize you’re standing at the base of San Gorgonio Peak—the highest point in Southern California at 11,503 feet. Looking up at that massive mountain from the floor of the pass gives you a perspective on scale that you just can't get from a car window at 80 mph.

The San Gorgonio Pass is a place of extremes. Extreme wind, extreme geology, and extreme importance to the California economy. It’s the place where the coast ends and the true West begins.

Actionable Insights for Travelers and Residents

- Check the Wind: Use the "Windy" app or NOAA's local forecast for the Banning Pass specifically. "San Bernardino" weather is not the same as pass weather.

- Fuel Up: Prices in the pass (especially Cabazon) can be significantly higher than in Beaumont or Indio.

- Safety First: If you see "High Wind Warning" signs and you are driving a van or SUV, move to the right lane. The gusts come out of the canyons unexpectedly and can push you into the next lane.

- Hidden Hiking: Try the PCT section starting from Snow Creek. It’s brutal but offers some of the best views of the "Twin Peaks" (San Jacinto and San Gorgonio) facing each other across the gap.

- Visit the Dinosaurs: Yes, the Cabazon Dinosaurs are a tourist trap, but they are a piece of California roadside history that everyone should see once. Plus, the museum inside has some... interesting... takes on geology that provide a fun contrast to the actual science of the fault line.

The San Gorgonio Pass doesn't care if you're in a hurry. It’s going to keep blowing, the plates are going to keep shifting, and the trains are going to keep rolling. Next time the wind shakes your car, just remember you're witnessing one of the most powerful natural engines in the world at work.