History books usually paint a picture of a salt-crusted prince standing on a prow, squinting at the horizon. We’re told he "discovered" the world. But honestly, Prince Henry—Infante Dom Henrique—barely left Portugal. He wasn't a sailor. He was a venture capitalist with a cross on his chest and a serious obsession with what lay beyond the "Sea of Darkness."

The actual route of Henry the Navigator isn't a single line on a map. It’s a slow, painful, multi-decade expansion down the coast of West Africa. It was driven by a mix of crusading zeal, a desperate need for gold, and the very real possibility of falling off the edge of the world. At least, that’s what his sailors thought.

For years, the limit was Cape Bojador. In modern-day Western Sahara, this spot was the "Point of No Return." The currents were violent. The winds were terrifying. Sailors genuinely believed the sun was so hot past that point that their skin would turn black or the water would start boiling.

Breaking the Barrier of Cape Bojador

It took fifteen expeditions over twelve years just to get past that one cape. Think about that. Gil Eanes finally did it in 1434. He didn't find sea monsters or boiling pits. He found some rosemary plants. That’s it.

This moment changed everything. Once the psychological wall of Bojador crumbled, the route of Henry the Navigator accelerated. It wasn't just about exploration anymore; it was about building a maritime empire. They were looking for the "River of Gold" and the mythical Christian king, Prester John. They wanted to bypass the Saharan trade routes controlled by Muslim merchants.

✨ Don't miss: How Long Ago Did the Titanic Sink? The Real Timeline of History's Most Famous Shipwreck

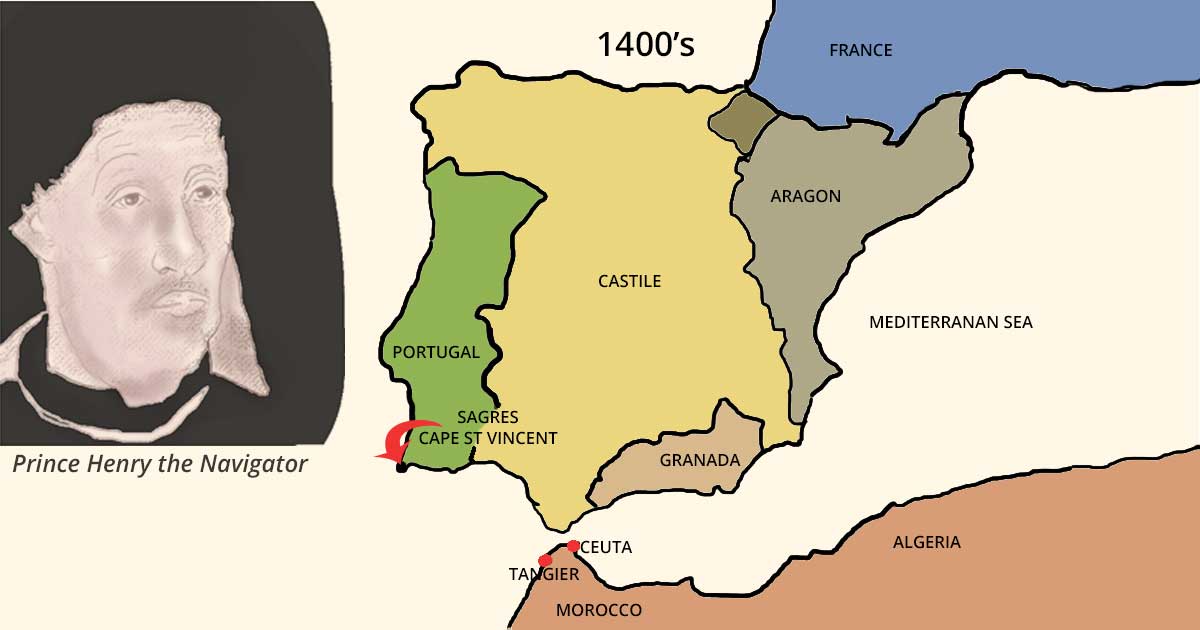

Portugal was a small, relatively poor country. They needed an edge. Henry provided the funding and the intellectual hub at Sagres. While the "School of Sagres" might be a bit of a historical exaggeration by later nationalists, he definitely gathered cartographers, astronomers, and shipwrights. They developed the caravel. This ship was the secret weapon. It had lateen (triangular) sails that let it sail against the wind. Without the caravel, the Portuguese would have been stuck forever waiting for the breeze to blow them home.

The Push Southward and the Realities of Trade

By the 1440s, the Portuguese had reached the Senegal River and Cape Verde. This is where the story gets darker. While we celebrate the "Age of Discovery," the route of Henry the Navigator also became the first modern blueprint for the transatlantic slave trade. In 1441, Antão Gonçalves brought the first captives back to Lagos, Portugal.

Henry took his "royal fifth" of the profits. He saw no contradiction between his role as the Grand Master of the Order of Christ and the enslavement of Africans. In his mind, he was saving souls. In reality, he was financing more voyages.

- 1444: Dinis Dias reaches the Senegal River.

- 1445: Álvaro Fernandes pushes further, likely reaching the coast of modern-day Guinea-Bissau.

- 1456: Alvise Cadamosto (a Venetian working for Henry) explores the Cape Verde Islands.

The coastline was meticulously mapped. They called these maps portolans. They were trade secrets. If you were caught leaking a map to the Spanish or the Genoese, it was basically treason. The Portuguese weren't just exploring; they were staking a claim. They erected padrões—stone pillars topped with crosses—along the African coast to say, "We were here first."

🔗 Read more: Why the Newport Back Bay Science Center is the Best Kept Secret in Orange County

The Science Behind the Sailing

You've got to wonder how they actually found their way back. Going down the coast was easy because the North Atlantic gyre carries you south. Getting home was the nightmare.

They developed a technique called the volta do mar (turn of the sea). Instead of hugging the coast on the way back, they would sail far out into the open Atlantic to the west, catching the prevailing winds that would eventually loop them back toward the Azores and then home to Lisbon. This required massive balls. You had to sail away from land into the unknown to eventually get home.

This "Great Circuit" is what eventually allowed Vasco da Gama to reach India and Columbus to hit the Caribbean. Henry’s captains were the ones who did the homework. They learned the stars. They began using the astrolabe and the quadrant to measure latitude by the height of the North Star.

They were basically the NASA of the 15th century.

💡 You might also like: Flights from San Diego to New Jersey: What Most People Get Wrong

Why the Route Stopped Where It Did

When Henry died in 1460, his explorers had reached roughly the coast of Sierra Leone. He didn't live to see the tip of Africa rounded. He didn't see the spice markets of Calicut. But he had broken the seal.

The route of Henry the Navigator established the feitoria system—fortified trading posts. Instead of conquering vast inland territories (which they couldn't do yet), the Portuguese sat on the coast and controlled the flow of goods. Gold, ivory, Malagueta pepper, and people.

It’s easy to look back and see a straight line to the modern world, but for the men on those ships, it was a series of terrifying, incremental crawls into the fog. They were limited by scurvy, wood rot, and the sheer vastness of the Atlantic.

Actionable Insights for the Modern History Buff

If you want to understand this era beyond the dry Wikipedia summaries, you need to look at the intersection of technology and geography.

- Visit Sagres: If you’re ever in the Algarve, go to the Fortaleza de Sagres. It’s a windswept plateau that feels like the end of the world. You’ll understand why they thought the sea was a monster.

- Study the Caravel: Look up the rigging of a 15th-century caravel versus a traditional square-rigged ship. The ability to "tack" or sail into the wind was the literal pivot point of world history.

- Read the Chronicles: Check out Gomes Eanes de Zurara’s Chronicle of the Discovery and Conquest of Guinea. He was Henry's contemporary. It’s biased as hell, but it gives you the raw, unfiltered mindset of the 1400s—the religious fervor, the greed, and the genuine curiosity.

- Acknowledge the Cost: Don't separate the navigation from the human trafficking. The routes mapped by Henry's captains became the literal paths used by slave ships for the next 400 years. Understanding the route means acknowledging the total legacy.

The exploration of the African coast wasn't just a "voyage." It was the start of a globalized economy. It shifted the center of power from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic, leaving the great Italian city-states in the dust and making Lisbon the richest city in Europe for a golden, fleeting moment.

To truly grasp the route of Henry the Navigator, stop looking for a destination. Look at the process—the "volta do mar," the rosemary at Bojador, and the slow, grinding movement of a small nation pushing itself into the deep ocean because they had nowhere else to go.