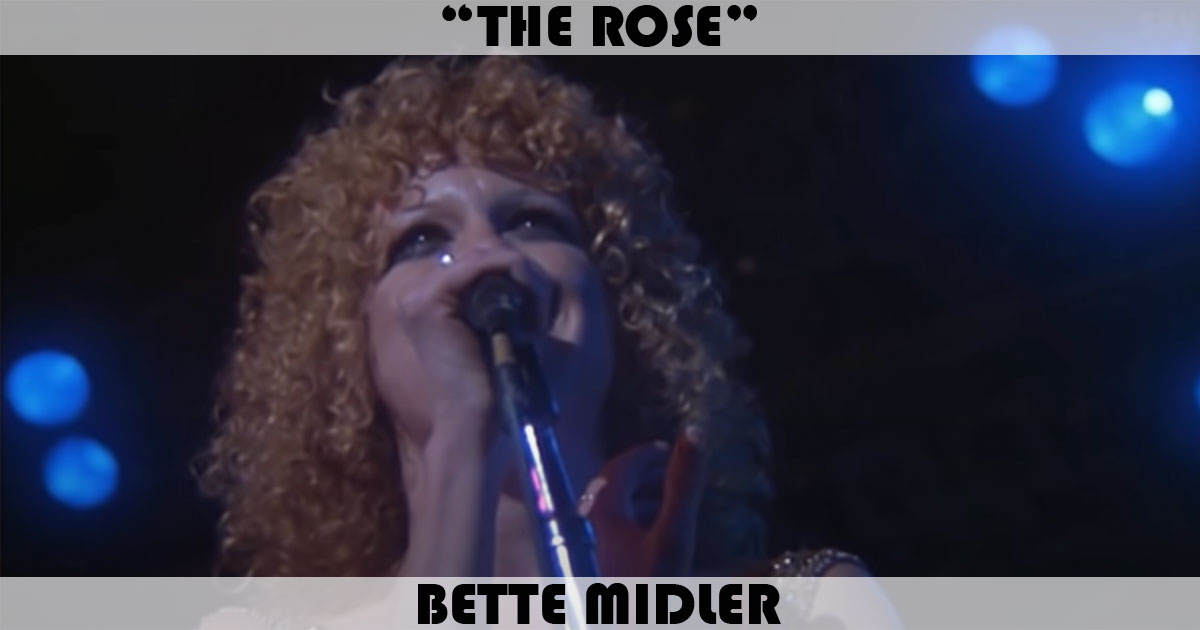

It starts with that lonely, repetitive piano riff. You know the one. It’s sparse, almost skeletal, before Bette Midler’s voice comes in—low, steady, and weary. Most people think the rose song by bette midler is just another cheesy wedding track or a karaoke staple for people who’ve had one too many chardonnays.

They’re wrong.

Actually, the history of this song is kinda messy. It wasn't written for a greeting card. It was written for a gritty, R-rated movie loosely based on the self-destruction of Janis Joplin. When Midler recorded it, she wasn't trying to create a "healing" anthem. She was playing a character named Mary Rose Foster, a rock star literally vibrating with exhaustion and loneliness.

The Song That Almost Didn't Happen

Amanda McBroom wrote the lyrics. She wasn't some titan of the music industry at the time; she was a songwriter who penned the tune while driving down the road. She heard a song on the radio that she hated—something about love being a "faucet" or some other weird metaphor—and she thought, "I can do better than that."

She got home and wrote the lyrics in about forty-five minutes.

It sat in a pile. The producers of the movie The Rose actually rejected it at first. They thought it was too slow. Too "hymn-like." They wanted something rock and roll. But Paul Rothchild, the legendary producer who had worked with the real Janis Joplin and The Doors, knew better. He pushed for it. He saw that the film needed a moment of stillness to balance out the screaming and the drugs and the glitter.

Why the Lyrics Hit Different

Let’s look at that first verse. "Some say love, it is a river, that drowns the tender reed." It’s basically a list of cynical definitions of love. It’s a razor, it’s a hunger, it’s an aching need.

Then comes the pivot.

The song argues that love isn't something that happens to you; it’s something you have to be brave enough to participate in. "It's the heart afraid of breaking that never learns to dance." That’s the line that usually gets the waterworks going. It’s a simple truth, but Midler delivers it with this specific kind of grit. She doesn't oversell it. In the 1979 studio version, her voice has this incredible control that slowly gives way to power.

By the time she hits the final stanza about the seed beneath the bitter snow, she’s not just singing a song. She’s making a promise.

📖 Related: Wrong Address: Why This Nigerian Drama Is Still Sparking Conversations

The Janis Joplin Connection

Even though the movie is titled The Rose, everyone in Hollywood knew it was the Janis Joplin story. The estate of Janis Joplin wouldn't grant the rights to her life story or her music, so the writers had to pivot. They created "Rose."

Bette Midler was already a star in the late 70s, but she was the "Divine Miss M"—a campy, high-energy cabaret queen. Nobody knew if she could handle the heavy, dramatic lifting required for a role this dark.

The recording of the rose song by bette midler served as her proof of concept. It proved she could be vulnerable. The single eventually hit number three on the Billboard Hot 100. It stayed there for five weeks. It even won her a Grammy for Best Female Pop Vocal Performance.

Think about the competition in 1980. You had disco dying out and New Wave starting to bubble up. You had Michael Jackson's Off the Wall and Billy Joel's Glass Houses. And here comes this quiet, piano-driven ballad about a flower. It shouldn't have worked.

It worked because it felt real.

Production Secrets from the Studio

Paul Rothchild was a perfectionist. He wanted the vocals to sound raw. If you listen closely to the original recording—not the remastered versions that polished everything—you can hear Midler’s breath. You can hear the slight imperfections.

The arrangement is deceptively simple.

- Piano

- A subtle string section that creeps in toward the end

- Midler’s voice

- Minimal backing vocals

The "build" of the song is what makes it a masterpiece of pacing. It starts in a whisper and ends in a roar. That’s a classic "power ballad" formula now, but in 1979, it felt much more like a theatrical soliloquy.

Cultural Impact and the "Wedding Song" Curse

It’s honestly a bit ironic that the rose song by bette midler is played at so many weddings. If you actually watch the movie, the song plays over the credits after [SPOILER ALERT] the main character dies of an overdose. It’s a song about survival and the possibility of love, written for someone who didn't survive and couldn't find love.

👉 See also: Who was the voice of Yoda? The real story behind the Jedi Master

But that’s the beauty of art. People take what they need from it.

Conway Twitty covered it and took it to number one on the country charts. Westlife covered it. LeAnn Rimes covered it. Even Christopher Lee—yes, Saruman himself—did a heavy metal-ish version of it.

None of them touch Bette.

There is a specific ache in her voice. She sounds like she’s lived every single line of that song. She sounds like she’s been the one afraid of the "living" and the one who felt the "luck" was only for the strong.

Technical Breakdown: Why it Works

If we’re getting nerdy about the musicology, the song is in the key of C Major. It’s remarkably easy to play on a piano. This accessibility is part of why it spread so fast. Anyone with a Year 1 piano book could figure out the chords.

But the melody is wide-ranging. It requires a singer who can transition from a chest voice to a head voice without it sounding like a gear shift in an old truck. Midler does this flawlessly.

The "hook" isn't a chorus. The song doesn't actually have a standard chorus-verse-chorus structure. It’s a linear progression. It’s one long thought.

Misconceptions and Urban Legends

Some people think the song is an old Irish folk tune.

Nope.

Some think it was written by Bette herself.

Wrong again.

There was even a weird rumor in the 80s that the song was about a specific person who died in the Vietnam War. While the lyrics are universal enough to apply to grief, Amanda McBroom has been very clear that it was a purely philosophical exercise about the nature of the heart.

✨ Don't miss: Not the Nine O'Clock News: Why the Satirical Giant Still Matters

The Legacy in 2026

Does it still hold up?

Yeah. It does.

In an era of hyper-processed vocals and AI-generated hooks, something as human as the rose song by bette midler stands out even more. It’s a reminder that you don’t need twenty writers and a team of Swedish producers to make a hit. You just need a piano, a perspective, and a singer who isn't afraid to sound a little bit broken.

If you’re a singer looking to tackle this, don’t try to imitate Midler. You’ll fail. She has a vibrato that is entirely unique to her anatomy. Instead, focus on the "story" of the lyrics.

Actionable Takeaways for Musicians and Fans

- For Singers: Focus on the "h" sounds. Midler uses breathiness on words like "heart" and "hunger" to create intimacy. Don't push the volume until the final verse.

- For Songwriters: Notice the lack of a bridge. The song succeeds because it’s a steady climb. Sometimes, you don't need a middle eight to create emotional impact.

- For Listeners: Go back and watch the final scene of the 1979 film. The context of the movie changes the "sweetness" of the song into something much more profound and tragic.

- For Curators: If you're building a "Best of the 70s" playlist, this belongs right between Fleetwood Mac and Elton John. It bridges the gap between rock and traditional pop.

The song is essentially a masterclass in emotional restraint. It proves that the loudest person in the room isn't always the one who gets heard. Sometimes, it's the person singing about a seed in the snow.

Keep the piano parts simple. Let the lyrics breathe. Don't overthink the metaphor. The Rose isn't just a flower; it's the part of us that stays hopeful when everything else is freezing over.

That’s why we’re still talking about it nearly fifty years later.

Key Statistics & Facts:

- Release Date: March 1980 (Single)

- Chart Peak: #3 Billboard Hot 100

- Certification: Platinum (RIAA)

- Composer: Amanda McBroom

- Producer: Paul A. Rothchild

- Grammy Wins: Best Female Pop Vocal Performance (1981)

To truly appreciate the vocal layering, listen to the 1979 soundtrack version rather than the "Greatest Hits" edits, as the soundtrack mix preserves the original dynamic range intended for cinema speakers.