If you want to understand the exact moment the 1960s finally died, don't look at 1969. Look at the Rolling Stones 1973. It was a year of profound, sweaty transition. They were essentially the biggest band in the world, yet they spent most of those twelve months looking over their shoulders at tax inspectors, heroin busts, and the fading ghost of their own creative peak.

Honestly, 1973 is the "hangover" year.

The band had just come off the massive high of Exile on Main St. and the legendary 1972 North American tour. By the time January 1973 rolled around, they weren't just musicians anymore. They were a traveling nation-state. But the wheels were starting to wobble. Mick Taylor was playing like a god, Keith Richards was deeper into his "pharmaceutical" phase than ever before, and Mick Jagger was busy becoming a global jet-set celebrity.

It was a weird time to be a Stone.

The Pacific Tour and the Ban That Changed Everything

The year started with a literal bang—or rather, a series of logistical nightmares. The Stones headed to the Pacific for the first time in ages, hitting Hawaii, Australia, and New Zealand. But there was a massive problem: Japan.

The Japanese government looked at the band’s drug history and basically said, "No thanks." Despite selling out tens of thousands of tickets at the Budokan, the Stones were banned from entering the country. It was a huge blow to their ego and their wallets. This wasn't just a scheduling hiccup. It signaled that while the world loved their music, the establishment was still terrified of what the Rolling Stones 1973 represented.

They ended up playing the "Winter Tour" in places like Honolulu and Sydney. If you listen to the bootlegs from this period—specifically the January 18th show in Honolulu—you hear a band that is incredibly tight but somehow frantic. Mick Taylor’s guitar work on "All Down the Line" is searing. It’s almost like they were trying to outrun their reputation.

The stage setup was stripped back compared to the theatrical madness that would come later in the decade. It was just the five of them, plus Bobby Keys on sax and Jim Price on trumpet, blowing the doors off every arena.

📖 Related: Break It Off PinkPantheress: How a 90-Second Garage Flip Changed Everything

Goat’s Head Soup: The Record Everyone Loves to Hate

By the time they got to the studio to follow up Exile, the vibe had shifted. They ended up at Dynamic Sound Studios in Kingston, Jamaica. Why Jamaica? Because most of them couldn't get into the U.S. or the UK for tax and legal reasons.

Jamaica in late '72 and early '73 wasn't the tourist paradise people imagine today. It was tense. It was hot. And the recording sessions for Goats Head Soup reflected that. If Exile was a basement party, Goats Head Soup was the murky, drug-fueled morning after.

Most critics at the time panned it. They called it lazy. They said the Stones had gone "soft" because of "Angie."

But they were wrong.

"Angie" was a massive hit, sure. It saved the band’s commercial standing. But the real meat of the Rolling Stones 1973 discography is in the darker tracks. Take "Dancing with Mr. D." It’s funky, sinister, and weirdly hollow. Or "100 Years Ago," which features some of the most underrated wah-wah guitar work Mick Taylor ever laid down.

The album reached Number 1 on both sides of the Atlantic. Despite the lukewarm reviews, the public was still hungry. But inside the band, the fractures were growing. Keith was frequently absent or nodding off. Jimmy Miller, the producer who had guided them through their "Golden Age" (Beggars Banquet through Exile), was also struggling with addiction. His grip on the sound was slipping. You can hear it in the mix—it’s denser, swampier, and less focused than their previous work.

The European Tour: Chaos in the Shadow of the Cold War

The autumn of 1973 saw the band embark on a European tour that felt like a military operation. They played behind the Iron Curtain (well, close enough) and dealt with constant police presence.

👉 See also: Bob Hearts Abishola Season 4 Explained: The Move That Changed Everything

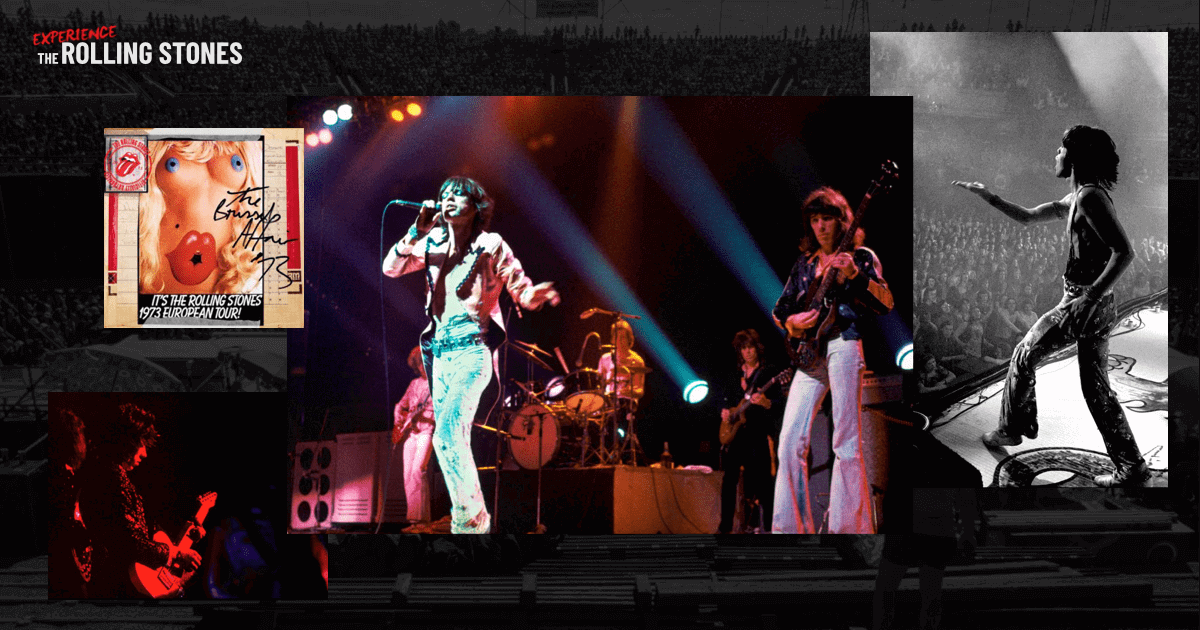

The Brussels Affair.

If you consider yourself a fan, you have to hear the Brussels recordings from October 17, 1973. Many historians and hardcore collectors argue this was the greatest the Rolling Stones ever sounded live. Ever.

The version of "Midnight Rambler" from that show is terrifying. It’s 13 minutes of pure tension. Jagger is howling, Bill Wyman’s bass is a leaden pulse, and Charlie Watts is holding the whole collapsing structure together with that signature swing. It was the peak of the Jagger/Taylor era. Taylor provided a melodic sophistication that the band never had before and certainly hasn't had since he left in 1974.

But the tour was also a mess. Bobby Keys, the legendary saxophonist and Keith's best friend, got kicked off the tour for filling a bathtub with Dom Perignon instead of showing up for the gig. Jagger was furious. The professional side of the band was clashing violently with the rock-and-roll-excess side.

The Legal Noose Tightens

While they were conquering Europe, the British legal system was closing in. On June 26, 1973, Keith Richards and Anita Pallenberg were arrested at their home in Chelsea. The police found a handgun, ammunition, and various substances.

This wasn't just another "pop star gets busted" story. Keith was facing serious jail time. It cast a shadow over everything the band did that year. Every time they crossed a border, there was a chance someone wouldn't be allowed through. It’s one of the reasons the Rolling Stones 1973 feels so paranoid. They were the world's greatest rock band, but they were also essentially fugitives.

The pressure began to change the music. The defiance of "Street Fighting Man" was being replaced by the weariness of "Coming Down Again."

✨ Don't miss: Black Bear by Andrew Belle: Why This Song Still Hits So Hard

Why 1973 Was Actually the End of an Era

A lot of people think the Stones' "Golden Age" ended when Mick Taylor left. I’d argue it ended in late 1973.

By the end of the year, the chemistry had fermented into something different. They had survived the '60s, survived Altamont, and survived the transition to stadium rock. But in 1973, the "business" of being the Stones began to outweigh the "art" of being the Stones.

Jagger was increasingly handling the logistics and the image. He was becoming the businessman-vocalist we know today. Keith was retreating into a haze, emerging only to deliver those razor-sharp riffs that kept the engine running.

And Taylor? He was bored. He was a virtuoso blues guitarist playing three-chord rockers, and his lack of songwriting credits was starting to grate. You can see it in the concert footage—he’s often standing off to the side, looking like he's in a different band entirely.

How to Experience the Best of the Rolling Stones 1973

If you want to move beyond the hits and really get what this year was about, you need to change your listening habits. Don't just loop "Angie."

- Listen to "Doo Doo Doo Doo Doo (Heartbreaker)": This is the Stones at their most socially conscious and gritty. It's a song about police brutality in New York, and the horn arrangement is pure 1973 funk-rock.

- Find the "Brussels Affair" official bootleg: Released officially by the band years later, this is the definitive document of their live power during this period.

- Watch the "Old Grey Whistle Test" footage: There are clips of them performing in the studio during this era that show the sheer charisma Jagger still wielded before the stadium spectacle took over.

- Analyze the lyrics of "Coming Down Again": It’s one of the few Keith-led vocals from this era, and it’s a heartbreakingly honest look at the toll their lifestyle was taking.

The Rolling Stones 1973 wasn't about perfection. It was about survival. They were a band transitioning from the raw energy of the club scene into the slick, corporate machinery of the modern concert industry. They did it with a cigarette in one hand and a bottle of Jack Daniels in the other, and they made some of the most interesting—if flawed—music of their lives.

To really appreciate this era, you have to look past the "greatest hits" narrative. Dig into the B-sides and the live recordings. Notice the interplay between Taylor's fluid leads and Keith's percussive rhythms. That specific sound—that 1973 sound—is a unique blend of British blues, Jamaican heat, and the encroaching darkness of the mid-70s. It never sounded quite like that again.

The next time you hear "Angie" on the radio, remember the context. It wasn't just a ballad. It was a lifeline for a band that was, for a moment, genuinely teetering on the edge of collapse. They didn't fall, though. They just kept rolling.