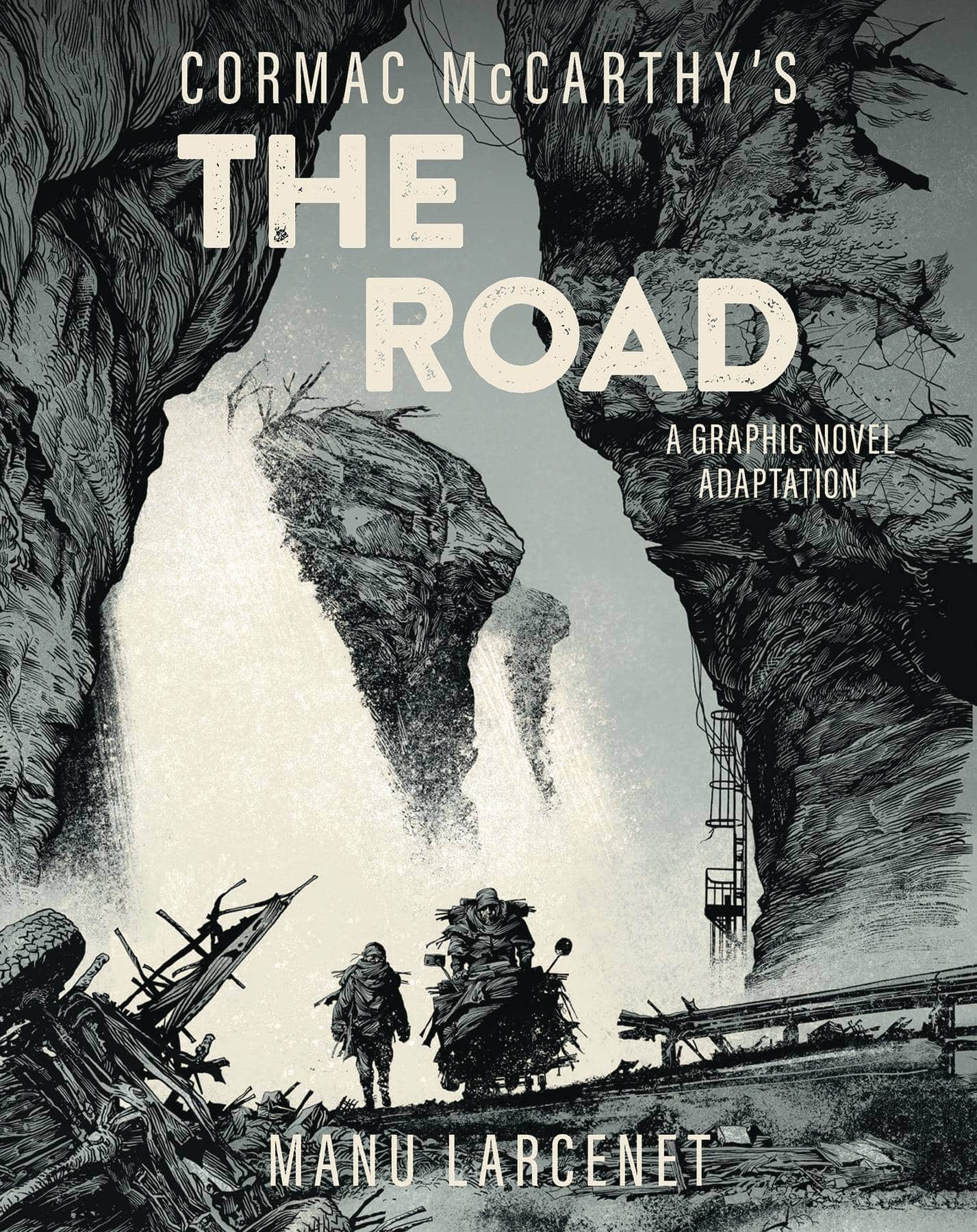

It is gray. Everything. The sky, the dirt, the water, even the skin of the two unnamed protagonists trekking across a shattered America. When Cormac McCarthy released The Road in 2006, he basically redefined how we imagine the end of the world. It wasn't about zombies or aliens; it was about the crushing, relentless silence of extinction. So, when news broke that French cartoonist Manu Larcenet was adapting it into a graphic novel, people were rightfully skeptical. How do you draw silence? How do you illustrate a book that is famous for having almost no descriptive color?

Honestly, the result is staggering.

Released in 2024, The Road graphic novel (or La Route) manages to do something the 2009 film struggled with. It captures the texture of the ash. Larcenet, known for his work on Blast and The Ordinary Victories, spent years meticulously rendering a world where the sun is a "cold autoptic light." It’s a massive undertaking. Adapting McCarthy is a trap for most because his prose is so rhythmic and biblical that losing the words usually means losing the soul of the story. But Larcenet leans into the visual void.

Why the art style matters more than the plot

If you’ve read the original book, you know the plot is a straight line. A father and his son walk south. They are hungry. They are scared. They hide from "bloodcults." They find a bit of food, then they lose it. That’s it. In a traditional comic, this could get boring fast.

Larcenet avoids this by using a style that feels like it was etched into stone with a needle. He uses a limited palette—mostly grays, blacks, and sickly sepias—to mimic the suffocating atmosphere of the "long dark." The panels are often huge, swallowing the tiny figures of the man and the boy. You feel the scale of their isolation. It's not just "post-apocalyptic art." It's an exercise in claustrophobic emptiness.

The detail is almost obsessive. You see every rib on the boy’s chest, every frayed thread on their rags, and the horrific, jagged remains of the burnt-out cities. McCarthy wrote about the "charred and limbless trunks of trees," and Larcenet actually draws every single one of them. It makes the world feel heavy. You can almost smell the wet soot coming off the page.

The challenge of McCarthy’s dialogue

McCarthy’s dialogue is famous for lacking quotation marks and being incredibly sparse.

"Are we still the good guys?"

"Yes. We're still the good guys."

"And we're carrying the fire?"

"And we're carrying the fire."

In the graphic novel, these lines are given space to breathe. Larcenet doesn't clutter the panels with word balloons. Sometimes, pages go by with no text at all, just the sound of the shopping cart wheels clicking over the asphalt. This is where the adaptation shines. It understands that in The Road, what isn't said is just as important as what is. The silence becomes a character.

✨ Don't miss: Priyanka Chopra Latest Movies: Why Her 2026 Slate Is Riskier Than You Think

Comparing the Graphic Novel to the 2009 Film

Most people remember Viggo Mortensen in the movie. He was great. But film, by nature, is a literal medium. You see the actors; you see the set. There’s a certain "Hollywoodness" that creeps in, even in a grim movie. The graphic novel feels more like the inside of McCarthy's head.

The book was always a fable. It was a nightmare.

By using ink and paper, Larcenet preserves that dreamlike (or nightmare-like) quality. The faces of the "bad men" they encounter aren't just dirty actors; they are ghoulish, distorted reflections of what humanity becomes when the grocery stores run out of food. There is a scene involving a basement—readers of the book know the one—that is far more terrifying in the graphic novel than it ever was on screen. The shadows do the work. Your brain fills in the rest of the horror.

Is it too dark?

Look, it’s The Road. It’s never going to be a fun Sunday morning read. But there’s a weird beauty in Larcenet’s work. He finds light in the strangest places: the glow of a stray lamp, the reflection in a puddle of grey water, the way the snow looks when it's falling through a collapsed roof.

Critics from outlets like The Guardian and Le Monde have pointed out that Larcenet’s background in darker, psychological French comics makes him the only person who could have pulled this off. He doesn't sanitize the violence. He doesn't make the father a hero. He’s just a dying man trying to keep a child alive in a world that has already died. It’s brutal.

What readers get wrong about the adaptation

One common misconception is that a graphic novel "dumb downs" a literary masterpiece. People think that because there are pictures, you don't have to think as hard. That’s nonsense, especially here.

Larcenet actually adds layers of subtext through visual motifs that McCarthy only hinted at. For instance, the recurring imagery of the shopping cart becomes a symbol of the old world’s consumerism rotting away. The way the man looks at his pistol—the two remaining bullets—is handled with a visual tension that words sometimes struggle to convey. You see his hand shake. You see the reflection in the boy's eyes.

🔗 Read more: Why This Is How We Roll FGL Is Still The Song That Defines Modern Country

Another thing: the ending.

Without spoiling it for the three people who haven't read the book or seen the movie, the ending of the graphic novel hits differently. It’s more meditative. It gives you more time to sit with the weight of the story’s "hope," such as it is.

The technical mastery of Manu Larcenet

Larcenet didn't just draw this; he lived it for years. To capture the specific look of the ash-covered world, he experimented with different textures and ink washes. The result is a book that feels tactile. If you run your fingers over the pages, you almost expect them to come away black with soot.

- Pacing: The book moves slowly. It forces you to look at the landscape.

- Character Design: The boy looks fragile, almost translucent. The man looks like he is turning into the very ash he walks through.

- Environment: The "road" itself isn't just a path; it's a decaying corpse of civilization.

If you’re a fan of the original 2006 novel, you might be worried that the graphic novel loses the "theological" weight of McCarthy’s prose. It doesn't. It just translates it into a different language. Instead of a "tabernacle" of trees, you see the cathedral-like ruins of a forest. The religious overtones remain, but they are etched into the scenery rather than spoken in the narration.

Why you should actually care about this now

We’re living in a time where post-apocalyptic media is everywhere. From The Last of Us to Fallout, we are obsessed with the end of the world. But most of those stories are "fun." They have leveling systems, or cool monsters, or badass survivors.

The Road graphic novel is a reminder of what an actual apocalypse would look like. No electricity. No "cool" scavenging. Just cold, hunger, and the terrifying question of whether being "the good guys" actually matters when there’s no one left to see you.

It’s a masterclass in visual storytelling. Even if you’ve read the book ten times, the graphic novel offers a new way to experience the story. It makes it visceral again. It makes the "fire" they carry feel much more fragile when you can see how dark the world around it really is.

How to approach the reading experience

Don't rush through this. It's not a superhero comic where you scan the bubbles and move on. You need to look at the backgrounds. Notice the things Larcenet hid in the ruins. There are stories in the debris—ghosts of the people who lived there before the sky turned gray.

💡 You might also like: The Real Story Behind I Can Do Bad All by Myself: From Stage to Screen

If you are a collector, try to get the large-format edition. The art deserves the extra space. The tiny mass-market versions don't quite capture the scale of the desolation.

Next Steps for Readers and Collectors

If you're looking to dive into this adaptation or the world of McCarthy, here is how to get the most out of it.

First, track down the Abrams ComicArts English edition or the original Dargaud French version if you appreciate the original printing quality; the paper stock used in these editions is specifically chosen to handle the heavy ink saturation of Larcenet’s grays.

Second, read the graphic novel alongside the original 2006 text. Seeing how Larcenet translates specific paragraphs—like the famous opening sequence about the "creature" in the cave—provides a fascinating look into the process of literary adaptation.

Finally, if you find Larcenet's style compelling, check out his previous work, Blast. It deals with similar themes of isolation, madness, and the darker side of the human condition, serving as a spiritual predecessor to his work on The Road. This isn't just a comic; it's a significant piece of 21st-century art that honors McCarthy's legacy while creating something entirely new.