You’ve felt it. That sudden, sickening lurch under your feet, the rattling of windows, and the immediate instinct to check your phone. Within minutes, the news breaks: a 5.2 magnitude earthquake. We all immediately look for that number. It’s our universal shorthand for "how bad was it?" But here’s the thing—when you hear people talk about the Richter scale today, they are almost always talking about a ghost.

Charles Richter changed the world in 1935. Before him, we mostly measured quakes by how much they scared people or knocked over chimneys. It was subjective. Richter wanted math. He wanted a way to rank the physical energy of a tremor using a logarithmic scale, meaning a 5.0 isn't just a little bigger than a 4.0; it’s ten times bigger in amplitude and releases about 32 times more energy.

It’s huge. It’s also, technically, not what modern scientists use anymore.

💡 You might also like: Which State Has Most Tornadoes: Why the Answer Isn’t Just Texas

What is a Richter Scale and How Does it Actually Work?

Back in the 1930s, Charles Richter and Beno Gutenberg were working at Caltech. They needed a way to categorize the local earthquakes happening in Southern California. They used a specific device called a Wood-Anderson torsion seismograph. This is a crucial detail because the original Richter scale—officially known as the Local Magnitude scale ($M_L$)—was designed specifically for that one instrument and for the specific crust of California.

The math is honestly pretty wild. Because earthquakes vary so much in size, Richter used a base-10 logarithmic scale. If you move from a magnitude 3 to a magnitude 4, the ground shakes 10 times harder. If you jump from a 3 to a 5, it’s 100 times harder.

But ground shaking (amplitude) isn't the same as the total energy released. For every whole number increase on the scale, the energy release increases by a factor of roughly 31.6. That’s why a magnitude 8.0 isn't just "twice as bad" as a 4.0. It’s millions of times more powerful. It’s the difference between a hand grenade and a nuclear stockpile.

Most people don't realize that the Richter scale has a "saturation" point. Think of it like a speedometer that tops out at 100 mph even if the car is going 150. For very large, distant earthquakes, the Richter scale simply stops being accurate. It can't "see" the massive energy of a magnitude 9.0.

The Shift to Moment Magnitude

By the 1970s, seismologists Thomas C. Hanks and Hiroo Kanamori realized the Richter scale was hitting a ceiling. They developed the Moment Magnitude Scale ($M_W$). This is what the USGS (United States Geological Survey) and other global agencies actually use today, even if the news anchor still calls it "Richter."

The Moment Magnitude scale looks at the physical "work" done by the earth. It measures:

- The rigidity of the rock.

- The distance the fault actually slipped.

- The total area of the fault plane that ruptured.

It's way more precise for the big ones. When the 1960 Valdivia earthquake hit Chile, it was a 9.5. The original Richter scale couldn't have handled that number accurately. But because the numbers on the $M_W$ scale were designed to roughly match Richter's original numbers for medium-sized quakes, the public never really noticed the switch. We just kept using the old name. It’s like calling every vacuum a "Hoover" or every tissue a "Kleenex."

Why These Numbers Sometimes Feel "Wrong"

Have you ever seen a 6.0 reported that caused massive destruction, while a 7.0 in another country barely made the news? This drives people crazy. It makes the scale feel fake.

Magnitude is just the energy at the source. It doesn't tell you the Intensity. For that, scientists use the Modified Mercalli Intensity (MMI) Scale. This uses Roman numerals (I to XII) to describe what actually happened on the ground.

A magnitude 7.0 deep in the ocean might have an intensity of II (barely felt). A magnitude 5.0 directly under a city with poor building codes might have an intensity of VIII (severe damage). The scale measures the "what," but the depth, the soil type, and the architecture determine the "so what." If you're standing on soft "jello" soil (like parts of Mexico City or San Francisco), the shaking gets amplified. If you're on solid granite, you might just feel a quick jolt.

💡 You might also like: Montgomery County school delays: Why the decision takes so long and how to track it

Logarithmic Reality: The Math of the Monster

Let's look at the actual energy. It's the best way to respect what these numbers mean.

If a magnitude 1.0 is like a small construction blast, a 3.0 is roughly equivalent to a large commercial blast. By the time you get to a 6.0—the kind of quake that starts breaking things—you’re looking at the energy of the Hiroshima atomic bomb.

Now, jump to a 9.0, like the Tōhoku quake in Japan in 2011. That released enough energy to literally shift the Earth's axis and shorten our days by a fraction of a microsecond. You cannot represent that kind of power on a linear 1-to-10 scale. You need the logarithm.

Breaking Down the Numbers

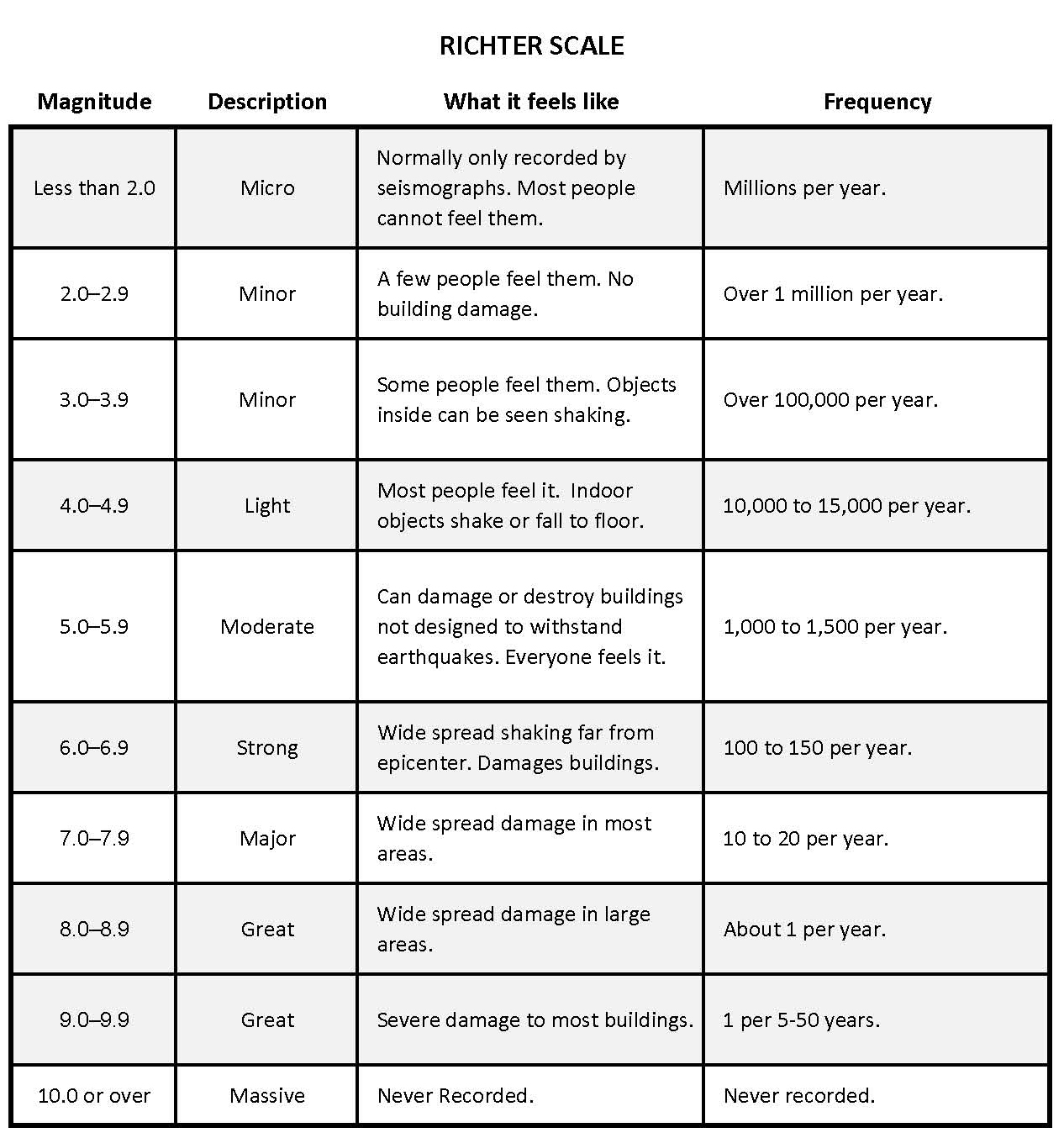

- 2.5 or less: Usually not felt, but recorded by seismographs. There are hundreds of thousands of these every year.

- 2.5 to 5.4: Often felt, but rarely causes structural damage.

- 5.5 to 6.0: Can cause slight damage to buildings; dangerous if you’re in an old brick house.

- 6.1 to 6.9: This is "Strong." It can cause a lot of damage in populated areas.

- 7.0 to 7.9: A "Major" earthquake. Serious damage over large areas.

- 8.0 or greater: "Great" earthquakes. Entire communities can be destroyed.

Common Misconceptions About Earthquake Scales

One of the biggest myths is that there is a "maximum" earthquake. While the scale is technically open-ended, the Earth has physical limits. The magnitude is limited by the length of the fault. To get a magnitude 10.5 earthquake, you would basically need a fault line that circles the entire planet. Not gonna happen. The largest ever recorded was that 9.5 in Chile.

Another weird thing? People think earthquakes are becoming more frequent because we see them in the news more. Honestly, they aren't. We just have way more seismographs than we used to. In the 1930s, we missed thousands of quakes because we didn't have the "ears" to hear them. Today, we have a global network that catches every tiny hiccup in the crust.

How to Use This Information

Knowing what a Richter scale is—and what its modern successor, Moment Magnitude, actually measures—changes how you react to the news.

When you see a magnitude reported, immediately look for two other things: Depth and Distance. A shallow quake (less than 10km deep) is almost always more dangerous than a deep one, even if the magnitude is lower. Energy dissipates as it travels through the earth.

If you live in an earthquake-prone area, don't obsess over the "number." Obsess over your surroundings. The scale tells you the power of the beast, but it doesn't tell you if your bookshelf is bolted to the wall.

Actionable Steps for Seismic Awareness

- Check the USGS "Did You Feel It?" Map: Whenever a quake hits, go to the USGS website. You can contribute your own data. This helps scientists map the Intensity (the Mercalli scale mentioned earlier) which is often more useful for emergency responders than the raw magnitude.

- Verify the Source: If a news outlet is reporting a "Richter" number for a quake in Turkey or Japan, know that they are using a colloquialism. Look for the $M_W$ (Moment Magnitude) for the scientifically accurate energy reading.

- Understand Your Soil: Use local geological survey maps to see if you live on "liquefaction" zones. This is where solid ground turns to liquid during a high-magnitude event. It matters more than the number on the scale.

- Ignore "Earthquake Weather": It’s a myth. There is no such thing. Earthquakes happen in blizzards, heatwaves, and hurricanes. The scale doesn't care about the sky; it only cares about the stress in the rocks miles beneath your feet.

The Richter scale was a stroke of genius that gave us a language for the Earth's violence. We've refined the language since then, but the core lesson remains: we live on a restless, moving puzzle, and these numbers are just our way of trying to measure the infinite power of the ground beneath us.