You’re sitting in your living room when the floor starts to wiggle. A few seconds later, the news anchor announces a "6.4 on the Richter scale." We’ve heard it a thousand times. It’s the gold standard for earthquake talk, right? Well, honestly, not really.

If you ask a seismologist today about the Richter magnitude scale, they’ll probably give you a polite, slightly exhausted smile. That’s because the scientific community largely moved on from it decades ago. Yet, the name sticks around like an old song that won’t leave your head. It’s basically the "Kleenex" of geology—a brand name that replaced the actual product in our collective vocabulary.

Understanding what this scale actually does, and why it's mostly retired, matters because it changes how we view the power of the earth. It’s not just a number. It’s a logarithmic monster that hides some pretty terrifying physics behind a simple decimal point.

What is the Richter Magnitude Scale anyway?

Back in 1935, Charles Richter and Beno Gutenberg at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) were trying to find a way to compare the earthquakes they were recording on their Wood-Anderson seismographs. Before this, people mostly used the Mercalli scale, which was based on intensity—basically, how much did the ground shake and how many chimneys fell over? The problem was that intensity is subjective. If an earthquake hits an empty desert, the intensity is low because nothing broke, even if the quake was massive.

Richter wanted something objective. He designed a scale that measured the actual amplitude of the waves recorded by a seismograph.

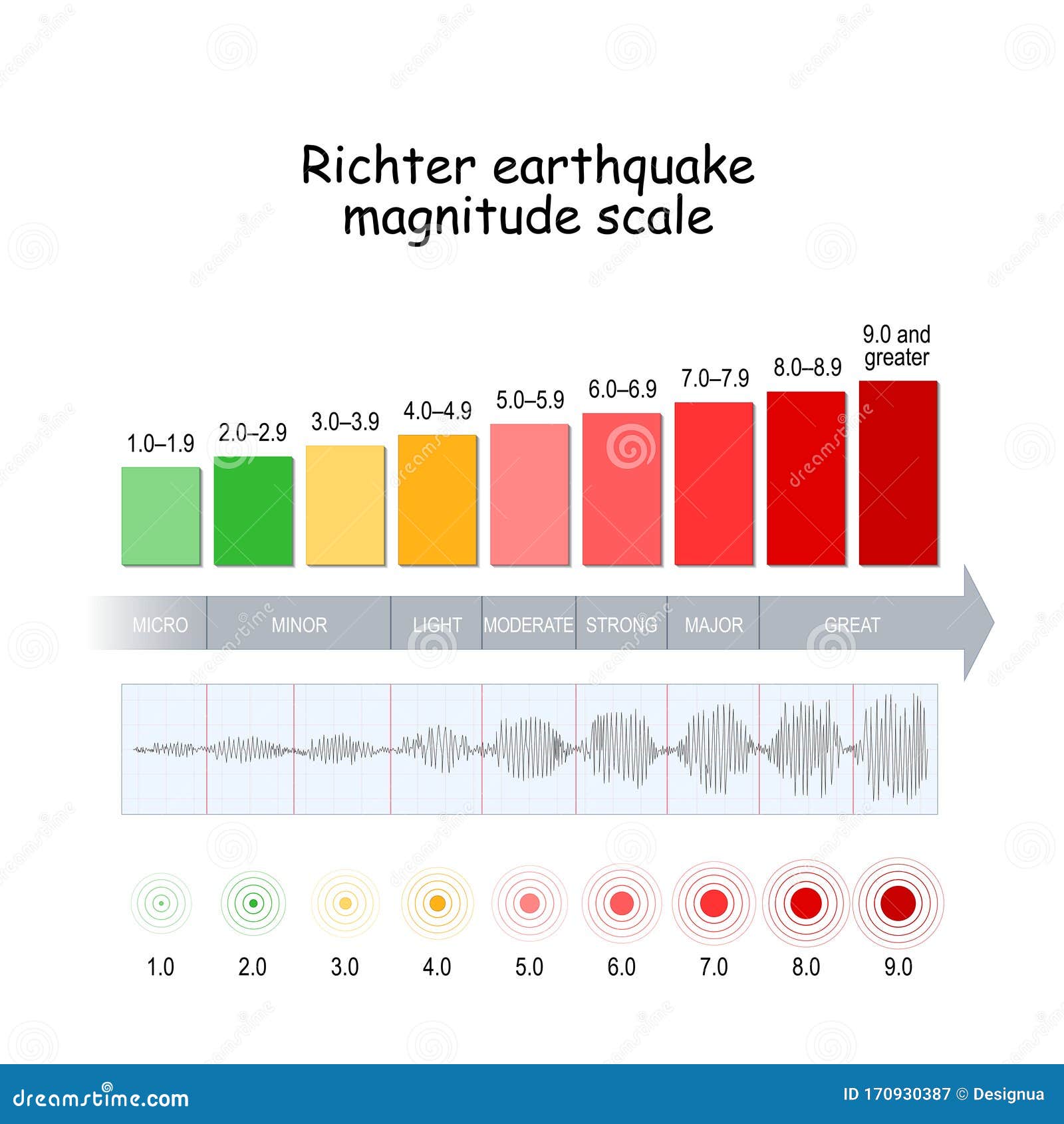

Here’s where it gets wild: the scale is logarithmic. This isn't like a ruler where 2 is twice as much as 1. No. On the Richter magnitude scale, each whole number increase represents a tenfold increase in the measured amplitude of the waves. If you jump from a 4.0 to a 6.0, the ground displacement is 100 times greater. But the energy? That’s the real kicker. Each step up is roughly 32 times more energy.

Think about that. A magnitude 7.0 doesn’t just shake a little more than a 6.0; it releases 32 times more "oomph." If you compare a 5.0 to a 9.0, you’re looking at over a million times more energy released. It’s the difference between a firecracker and a nuclear blast.

The Flaw in the Math

The Richter scale was originally tailored specifically for Southern California. It was meant for a specific type of seismograph at a specific distance from the epicenter. It was local.

As seismology went global, scientists realized the Richter scale had a "saturation" problem. When earthquakes got really big—think the 1960 Valdivia quake in Chile—the Richter scale basically hit a ceiling. It couldn't accurately measure the sheer amount of energy because the high-frequency waves it relied on would level off, even if the earthquake was getting longer and deeper.

This is why, since the late 1970s, experts have used the Moment Magnitude Scale (Mw).

If you see a 7.8 reported today by the USGS (United States Geological Survey), they are almost certainly using Moment Magnitude, not Richter. Moment Magnitude looks at the physical "moment" of the earthquake: how much the fault slipped, how long the rupture was, and the rigidity of the rock that broke. It’s more accurate for the big ones. But because the public knows the name "Richter," news outlets keep using it as a shorthand.

💡 You might also like: Finding Your Way with Hickory County MO GIS: What Most People Get Wrong

Why the Richter Magnitude Scale still sticks in our heads

Why do we keep calling it Richter? Habit. It’s easy to say. "7.2 on the Moment Magnitude Scale" sounds like a mouthful during a breaking news segment.

Also, for smaller earthquakes (under magnitude 4.0 or 5.0), the Richter scale and the Moment Magnitude scale usually produce very similar numbers. For the "micro-quakes" that happen thousands of times a day, Richter’s math still holds up pretty well. It’s only when the earth starts truly ripping itself apart that his original formula fails to capture the scope of the disaster.

The Real-World Impact: What the Numbers Feel Like

Numbers on a screen are abstract. Let’s talk about what actually happens on the ground.

- 2.0 to 3.0: You probably won't feel it unless you’re sitting perfectly still in a quiet room on a high floor. These happen millions of times a year.

- 4.0 to 5.0: This feels like a heavy truck rumbling past your house. Windows might rattle. Some fragile things might fall off a shelf. You’ll definitely know it happened.

- 6.0 to 7.0: Now we’re in dangerous territory. This can cause significant damage in populated areas. Chimneys fall. Walls crack.

- 8.0 and up: This is "Great Earthquake" status. It can destroy entire communities near the epicenter. The shaking can last for minutes.

The 1906 San Francisco earthquake is estimated to have been about a 7.9. The 2011 Tohoku earthquake in Japan was a 9.1. That 1.2 difference on the scale sounds small, but in terms of energy, the Japan quake was dozens of times more powerful.

The Depth and Distance Factor

A common mistake people make is looking only at the magnitude and assuming it dictates the damage. It doesn't.

✨ Don't miss: Windows 11 Pro Upgrade: Why Most People Are Still Overpaying

I remember the 2001 Nisqually earthquake in Washington State. It was a 6.8. That’s a big number! But because it was deep—about 32 miles underground—the energy had a lot of rock to travel through before it hit the surface, which dampened the blow. Contrast that with the 2010 Haiti earthquake, which was a 7.0 (barely "bigger" on paper) but only 8 miles deep. The proximity to the surface, combined with poor infrastructure, turned it into one of the deadliest events in human history.

Distance also matters. Being 50 miles away from a 7.0 is a very different experience than being 5 miles away. The Richter scale doesn’t tell you your personal risk; it only tells you how much energy the "bomb" had at its source.

Measuring the Unmeasurable

We have to talk about how we get these numbers. Seismographs are essentially weighted pens that stay still while the earth moves under them. Modern ones use electronic sensors and magnets, but the principle is the same.

When an earthquake hits, it sends out different types of waves. First come the P-waves (primary), which are fast and compress the ground like an accordion. Then come the S-waves (secondary), which move side-to-side and do more damage. By measuring the time gap between these waves, scientists can figure out exactly where the earthquake started—the hypocenter.

Richter’s genius was taking that raw data and turning it into a single, digestible number. He simplified the chaos of the earth’s crust into a 1-to-10 scale that a person reading the morning paper could understand. Even if it's technically outdated for large-scale events, his contribution gave us a language for disaster.

Practical Steps for Living in Earthquake Country

Since we can't stop the earth from moving and the scale only tells us what happened after the fact, the focus has to be on preparation. If you live in a seismic zone, "knowing the Richter scale" is less important than knowing your home's structural integrity.

- Check your foundation: In many older homes, the house isn't actually bolted to the foundation. During a 6.0 or higher, the house can literally slide off. Bolting is a relatively cheap retrofit that saves the entire structure.

- Secure the "High-Kill" items: Most injuries in earthquakes aren't from collapsing buildings; they are from falling objects. Secure your bookshelves to the wall. Use museum wax for vases. Most importantly, strap your water heater. If a quake hits, you’ll want that 50 gallons of clean water.

- Drop, Cover, and Hold On: Forget the "doorway" myth. Modern doorways aren't stronger than the rest of the house. Get under a sturdy table. Protect your head.

- Understand the "Modified Mercalli": If you want to know how a quake actually affected your area, look for the Mercalli intensity map on the USGS website after an event. It uses Roman numerals (I to XII) to describe the actual shaking felt in specific neighborhoods. This is often more useful for regular people than the Richter magnitude.

The Richter magnitude scale remains a monumental achievement in the history of science. It shifted our perspective from "God is angry" to "The earth is a measurable, physical system." Even if we use different math today, we owe our understanding of the shaking earth to that 1935 breakthrough in a California lab.

The next time you hear a number on the news, remember: it’s not just a digit. It’s a logarithmic representation of the staggering power buried beneath your feet. Respect the scale, but prepare for the intensity.