It was cold. April 4, 1968, wasn't just another campaign stop for Robert F. Kennedy. It was a nightmare. He was in Muncie, Indiana, when he heard the news: Martin Luther King Jr. had been shot in Memphis. By the time his plane touched down in Indianapolis, King was dead.

The city was a tinderbox.

Police told Kennedy they couldn't guarantee his safety. They basically told him to stay away from the African-American neighborhood where a crowd had already gathered. Kennedy ignored them. He climbed onto the back of a flatbed truck in a parking lot at 17th and Broadway. He didn't have a teleprompter. He didn't have a speechwriter’s polished draft. He had a few scribbled notes in his jacket pocket and a heavy heart.

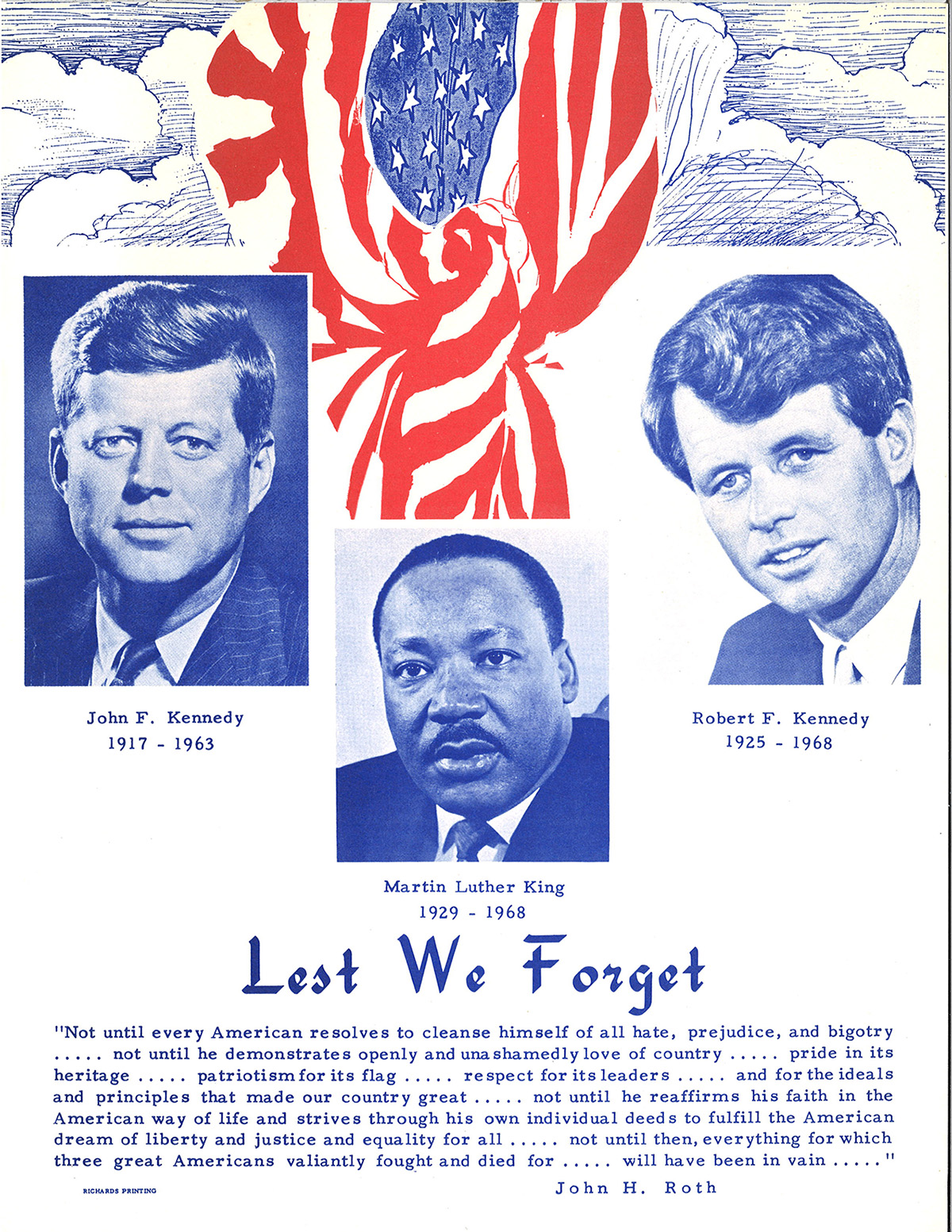

What followed—the RFK MLK death speech—is widely considered one of the most powerful instances of political rhetoric in American history. But it wasn’t just "rhetoric." It was a man who had lost his own brother to an assassin's bullet trying to stop a country from tearing itself apart.

The moment the world stopped

People in the crowd didn't even know. Can you imagine that? In 1968, information didn't move at the speed of a push notification. Many of the people standing in that gravel lot were there to cheer for a presidential candidate. They were smiling. They were excited.

Then Bobby spoke.

"I have some very sad news for all of you," he began. His voice was shaky. It was thin. When he finally said the words—that Martin Luther King had been shot and killed—the sound that came from the crowd wasn't a shout. It was a collective shriek. A wail.

He had to sit with that for a second.

Honestly, most politicians would have leaned into the anger. Or they would have given some canned response about "thoughts and prayers." Kennedy did something different. He quoted Aeschylus. He spoke about the "pain which cannot forget" falling drop by drop upon the heart. He didn't talk down to them. He talked with them.

🔗 Read more: Elecciones en Honduras 2025: ¿Quién va ganando realmente según los últimos datos?

Why the RFK MLK death speech worked when others failed

While cities like Chicago, Baltimore, and Washington D.C. erupted in flames and riots that night, Indianapolis stayed quiet. That’s the "miracle" people always talk about. But it wasn't magic. It was empathy.

Kennedy did something he almost never did in public: he talked about his brother, JFK.

"For those of you who are Black—considering the evidence there evidently is that there were white people who were responsible—you can be filled with bitterness, with hatred, and a desire for revenge. I can also feel in my own heart the same kind of feeling. I had a member of my family killed, but he was killed by a white man."

This was the first time he had spoken so directly about the assassination in a public speech. It broke the barrier. He wasn't a rich Senator from Massachusetts in that moment; he was a grieving brother. He was human.

The raw anatomy of the speech

The speech lasted barely five minutes.

It’s short. Really short.

If you look at the transcript, it’s not particularly complex. He used words like love, wisdom, and compassion. He called for an end to the "savage" nature of man. Most people forget that he actually apologized for the news he was delivering. He felt responsible for being the messenger of such grief.

There was no security detail surrounding him on that truck. No bulletproof glass. Just a guy in a topcoat standing in the dark.

💡 You might also like: Trump Approval Rating State Map: Why the Red-Blue Divide is Moving

The stuff history books leave out

Everyone loves the "peace" narrative, but we should be real about the context. The Indianapolis police were terrified. They literally refused to go into the park with him. Kennedy’s own advisors, like Adam Walinsky, were frantic. They thought he was walking into a riot.

And let’s be honest: one speech didn't "fix" racism in Indiana.

Indiana had a deeply troubled history with the Klan and segregation. The peace that night was fragile. It was held together by the sheer shock of the moment and the fact that Kennedy stayed in the neighborhood after the speech. He didn't just drop the news and bolt for a hotel. He stayed. He shook hands. He looked people in the eye.

The Aeschylus quote

The poem he quoted is from Agamemnon. Kennedy had memorized it after his brother died. It goes:

"In our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God."

Think about that. "The awful grace of God." It’s a contradiction. It suggests that wisdom only comes through absolute, crushing suffering. It was a heavy thing to say to a crowd that was already suffering so much. But it resonated because it didn't offer a cheap "it’ll be okay" solution. It acknowledged that things were, in fact, terrible.

What we can learn from it in 2026

We live in an era of "managed" communication. Everything is focus-grouped. Everything is scrubbed for "brand safety."

The RFK MLK death speech was the opposite of brand safe. It was dangerous. It was vulnerable.

📖 Related: Ukraine War Map May 2025: Why the Frontlines Aren't Moving Like You Think

If you're a leader, or even just someone trying to navigate a crisis, the lessons are pretty clear. You don't need a 40-page slide deck to move people. You need to show up. You need to tell the truth, even when the truth is ugly. And you need to find a common thread of humanity.

Kennedy didn't ask for votes that night. In fact, he didn't mention the election once. He just asked people to go home and say a prayer for the King family and for the country.

Actionable steps for processing historical rhetoric

If you really want to understand the impact of this moment, don't just read the transcript. You have to experience it.

- Watch the grainy footage. Look at Kennedy’s hands. He’s shaking. He’s gripping the notes so hard they’re crumbling. That physical manifestation of grief is what the transcript misses.

- Read the "Other" speech. Kennedy gave another speech the next day in Cleveland, often called the "On the Mindless Menace of Violence" speech. It’s the intellectual companion to the Indianapolis remarks and dives deeper into why violence is a "leaden" reality of American life.

- Visit the Landmark. If you’re ever in Indianapolis, go to the Landmark for Peace Memorial at Martin Luther King Jr. Park. It’s where the speech happened. It’s quiet now, but you can still feel the weight of what happened there.

- Contextualize the grief. Remember that Robert Kennedy himself would be assassinated just two months later in June 1968. That adds a layer of tragic irony to his calls for peace that is hard to ignore.

The legacy of the speech isn't just that it "prevented a riot." It’s that it provided a template for how to speak to one another when the world feels like it’s falling apart. It wasn't about being a politician; it was about being a person.

He ended the speech by saying "Let us dedicate ourselves to what the Greeks wrote so many years ago: to tame the savageness of man and make gentle the life of this world."

It’s a tall order. We’re still working on it.

How to use these insights today

- Prioritize Presence: In a crisis, showing up physically (or authentically) matters more than the "perfect" statement.

- Embrace Vulnerability: Shared pain is often the only bridge between opposing groups.

- Keep it Brief: When emotions are high, less is almost always more.

Robert Kennedy's address remains a masterclass because it wasn't a performance. It was an act of service to a grieving community. It reminds us that even in our darkest hours, there is a way to reach across the divide—if we are brave enough to be honest about our own scars.