Hip-hop in 1995 wasn't ready. Not really. When the Return of the 36 Chambers: The Dirty Version dropped, it felt less like a studio album and more like a police report from a chaotic night in Brooklyn. It was the second solo outing from the Wu-Tang Clan’s internal roster, following Method Man’s Tical, and it effectively blew the doors off what people expected from a "rapper."

Ol’ Dirty Bastard (born Russell Jones) didn't just rap. He growled. He sang off-key. He yelled. He made weird bird noises. Honestly, if you listen to it today, it still sounds like it’s coming from another planet. While RZA’s production provided the gritty, dusty basement aesthetic that defined the Wu-Tang's early "Shaolin" sound, ODB provided the soul. Or rather, the warped, drunken, hyper-energetic version of soul that only he could conjure.

The Raw Sound of Return of the 36 Chambers

You can't talk about this album without talking about the messiness. It’s intentional. Unlike the polished radio hits of the mid-90s, this record sounds like it was recorded through a layer of New York City soot. The opening track alone, "Intro," goes on for nearly five minutes of rambling, shouting, and hyping up the Wu-Tang Clan. It’s a test. If you can get past the intro, you’re in the club. If not, you’re missing out on some of the most avant-garde hip-hop ever pressed to wax.

Take "Shimmy Shimmy Ya." It is arguably one of the most recognizable beats in the history of the genre. RZA used a simple, infectious piano loop that feels playful yet ominous. But it’s ODB’s delivery—"Oh baby I like it raw"—that cemented the track in the cultural zeitgeist. He wasn't trying to be a lyricist in the traditional sense. He wasn't trying to out-rhyme Inspectah Deck or GZA. He was trying to be a character.

Most people don't realize how much of a technical gamble this album was. The recording sessions at 36 Chambers Studio were reportedly chaotic. RZA has mentioned in various interviews, including his book The Wu-Tang Manual, that ODB was the hardest member to pin down. You didn't just tell ODB to get in the booth; you waited for the spirit to move him. Usually, that involved a lot of alcohol and a lot of spontaneous energy. This spontaneity is what gives the Return of the 36 Chambers its lasting power. It feels alive. It feels like it could fall apart at any second, but it never quite does.

Why the "Dirty Version" Tag Actually Matters

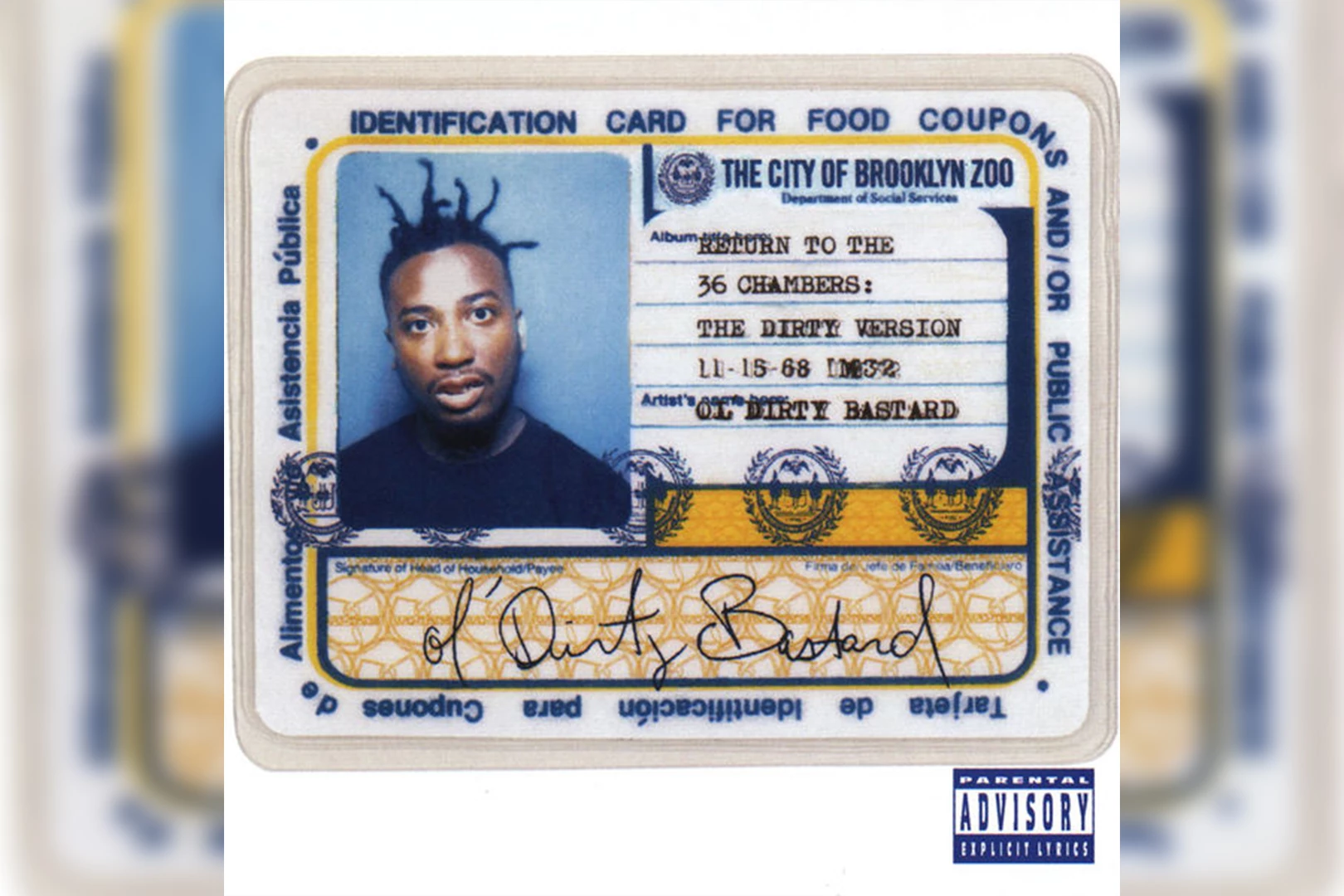

The title wasn't just a marketing gimmick. "The Dirty Version" referred to the unrefined, unedited nature of the tracks. At the time, the industry was moving toward a slicker, "Shiny Suit" era led by Puff Daddy and Bad Boy Records. ODB was the antithesis of that. He was the guy who famously took a limousine to pick up his food stamps with a camera crew in tow. That specific brand of "keeping it real" wasn't a brand for him; it was just his life.

💡 You might also like: Ashley My 600 Pound Life Now: What Really Happened to the Show’s Most Memorable Ashleys

The album is packed with features from the Wu-Tang family. Raekwon, Method Man, GZA, and Ghostface Killah all show up, but they often play second fiddle to ODB’s magnetism. In "Brooklyn Zoo," ODB carries the entire track with a feral intensity. There is no hook. There is no bridge. It is just one long, aggressive verse that sounds like a threat. It’s beautiful in its ugliness.

- Production: RZA used a mix of the Ensoniq EPS and the ASR-10 to craft these beats.

- Atmosphere: The use of Kung Fu movie samples wasn't just a background noise; it was a thematic framework that tied ODB’s madness to the Clan’s overarching mythology.

- Legacy: This album paved the way for every "weird" rapper that followed, from Danny Brown to Tyler, The Creator.

Misconceptions About ODB's Skill Level

There’s this weird idea that ODB wasn't a "good" rapper. That he was just a crazy guy who got lucky with a genius producer. That’s total nonsense. If you listen closely to his pocket on tracks like "Snakes" or "Damage," his timing is actually incredible. He’s rapping around the beat, slipping in and out of the rhythm in a way that’s closer to jazz than traditional 4/4 boom-bap.

He understood the power of the voice as an instrument. He used his raspy tone to create texture. When he sings on "The Drunk Game (Sweet Sugar Pie)," he knows he's out of tune. He’s leaning into it. It’s a performance piece. He was a student of soul legends like James Brown and Rick James, and you can hear that DNA in every grunt and scream. He was a bluesman trapped in a rapper’s body during the golden age of NYC hip-hop.

The Cultural Weight of 1995

In 1995, hip-hop was in a state of flux. The West Coast was dominant with G-Funk, and the South was just starting to bubble up with Outkast and Goodie Mob. The Return of the 36 Chambers helped solidify the East Coast's stranglehold on the "hardcore" narrative. It wasn't just music; it was a lifestyle. People wore the Wallabees, the oversized parkas, and the Wu-Tang "W" like a badge of honor.

The album also dealt with heavy themes, even if they were buried under ODB’s humor. There’s a lot of talk about street survival, poverty, and the paranoia of the 90s crack era. But because ODB presented it through the lens of a "drunken master," it was more digestible. He was the trickster figure of the Wu-Tang Clan. He could say the things that others couldn't because everyone just assumed he was high or out of his mind.

📖 Related: Album Hopes and Fears: Why We Obsess Over Music That Doesn't Exist Yet

Technical Brilliance in RZA’s Minimalist Era

RZA was at his absolute peak here. He wasn't using the lush strings or high-end mixing that would define later Wu projects. This was the "dirty" era. He was using filtered basslines that sounded like they were coming from a neighbor’s apartment. He was using drum breaks that were slowed down until they felt heavy and sluggish.

The track "Cuttin' Headz" is a perfect example of this. It features RZA and ODB basically just messing around, but the chemistry is undeniable. It feels like a freestyle session in a bedroom. By keeping the production sparse, RZA allowed ODB’s personality to fill the entire frequency range. You didn't need a complex melody when you had ODB screaming "Yo!" every four bars.

How to Appreciate the Album Today

If you’re coming to this album for the first time in 2026, you have to shed your expectations of modern production. There is no 808-heavy sub-bass. There is no Auto-Tune. There is no "perfect" mix. This is an artifact of a time when hip-hop was still experimental and dangerous.

To really get the most out of Return of the 36 Chambers, you have to listen to it as a cohesive piece of art, not just a collection of singles. Yes, "Shimmy Shimmy Ya" and "Brooklyn Zoo" are the hits, but the deep cuts like "Goin' Down" and "Proteck Ya Neck II the Zoo" are where the true flavor lives.

- Step 1: Use high-quality headphones. The subtle layers of RZA’s production—the hiss of the vinyl samples, the background chatter—are half the experience.

- Step 2: Look up the lyrics, but don't take them literally. ODB uses a lot of slang and Five-Percent Nation references that might be obscure, but the feeling is what matters.

- Step 3: Watch the old music videos. The visual aesthetic of ODB—the braids, the missing teeth, the wild eyes—is essential to understanding the music.

The Tragedy and the Triumph

It’s hard to talk about this record without acknowledging the tragedy of Russell Jones. He struggled with mental health and substance abuse for years before his passing in 2004. Some people look back at this album and see the beginning of a downward spiral. But that’s a reductive way to look at genius.

👉 See also: The Name of This Band Is Talking Heads: Why This Live Album Still Beats the Studio Records

The Return of the 36 Chambers is a triumph of individuality. In a genre that often rewards conformity and following trends, ODB was entirely, unapologetically himself. He didn't care if he sounded "good." He cared if he sounded real. And thirty years later, he still sounds more real than 90% of what’s on the charts.

Practical Ways to Dive Deeper into the Wu-Legacy

If this album clicks for you, don't stop there. The Wu-Tang universe is massive.

- Listen to GZA’s Liquid Swords: If ODB is the chaotic energy of the Wu, GZA is the cold, calculated logic. It was released the same year and acts as a perfect tonal balance.

- Check out Only Built 4 Cuban Linx: Raekwon’s "Purple Tape" is the cinematic, crime-thriller version of the Wu-Tang sound.

- Read The Wu-Tang Manual: It gives incredible insight into the philosophy and the technical tools used to create these sounds.

The Return of the 36 Chambers isn't just a nostalgic trip. It’s a masterclass in how to be an artist. It’s a reminder that your flaws—your off-key singing, your weird noises, your messy thoughts—can actually be your greatest strengths if you have the courage to put them on tape. Dirt is only a bad thing if you’re trying to stay clean. ODB knew that the dirt is where things grow.

To truly understand the impact of this work, go back and listen to the song "Raw Hide." Notice how the beat feels like it's dragging its feet, and how ODB and Method Man just dance over it. It’s effortless but impossible to replicate. That is the essence of the Wu. That is why we are still talking about this album decades later. It wasn't just a return to the 36 chambers; it was an expansion of what those chambers could hold.