If you want to understand the exact moment the 20th century stopped dreaming about the stars and started worrying about the bill, you have to listen to I.G.Y. by Donald Fagen. It’s the opening track of his 1982 masterpiece, The Nightfly. Honestly, it’s one of the most deceptively upbeat songs ever recorded. You hear that shimmering, ultra-clean production—the kind of sonic perfectionism that Fagen and Walter Becker spent years obsessing over in Steely Dan—and you might think it’s just a celebration of progress.

It isn't. Not really.

The song’s title refers to the International Geophysical Year. This was a global scientific project that ran from July 1957 to December 1958. It was a time when the world's brightest minds were collaborating on Antarctic research, satellite launches, and mapping the ocean floor. To a kid growing up in the late fifties, like Fagen, the future felt inevitable. It felt shiny. It felt like we were about to fix everything.

But when Fagen released this in 1982, the vibe was different. The Cold War was freezing over again. The sleek, chrome-plated optimism of the Eisenhower era had curdled into the cynical reality of the early eighties. That tension is exactly what makes the song a masterpiece. It captures a specific brand of American "techno-optimism" while winking at the listener from the other side of the mirror.

The Sound of Perfection (and Pain)

Recording I.G.Y. by Donald Fagen was a nightmare.

Ask any studio engineer from the eighties about The Nightfly sessions. They’ll probably get a thousand-yard stare. Fagen was notoriously demanding. He wasn't just looking for "good" takes; he was looking for a level of precision that barely felt human.

Take the drum track. This was one of the first major albums to heavily utilize Roger Nichols’ "Wendel" drum sampler. Fagen wanted the consistency of a machine but the "feel" of a human, which is a bit of a paradox. The result is a beat that is so steady it’s almost eerie. It’s the sound of a pristine laboratory.

Then there's the horn section. It’s tight. It’s crisp. It’s punchy. You have legendary players like Randy Brecker and Michael Brecker contributing to these sessions. They weren't just playing notes; they were building a sonic architecture.

The vocals are layered with a complexity that rivals 10cc or Queen, but it’s filtered through a jazz-pop sensibility. Every "ooh" and "ahh" is exactly where it needs to be. When you listen to it on a high-end system today, it still sounds better than 99% of what’s released now. It’s a benchmark for high-fidelity audio.

✨ Don't miss: The Lil Wayne Tracklist for Tha Carter 3: What Most People Get Wrong

What the Lyrics are Actually Saying

"Standing tough under stars and stripes / We can tell / This dream's in sight."

On the surface, those lyrics from I.G.Y. by Donald Fagen sound like a patriotic anthem for the Space Age. Fagen name-checks the "New Frontier," a direct nod to John F. Kennedy’s rhetoric. He sings about undersea trains connecting New York to Paris in ninety minutes. He talks about "machines to make big decisions" and "programmed dolls to check out vice."

It’s a world where "leisure time" is the only thing we have to worry about because technology has solved the drudgery of existence.

But there’s a layer of irony thick enough to cut with a knife.

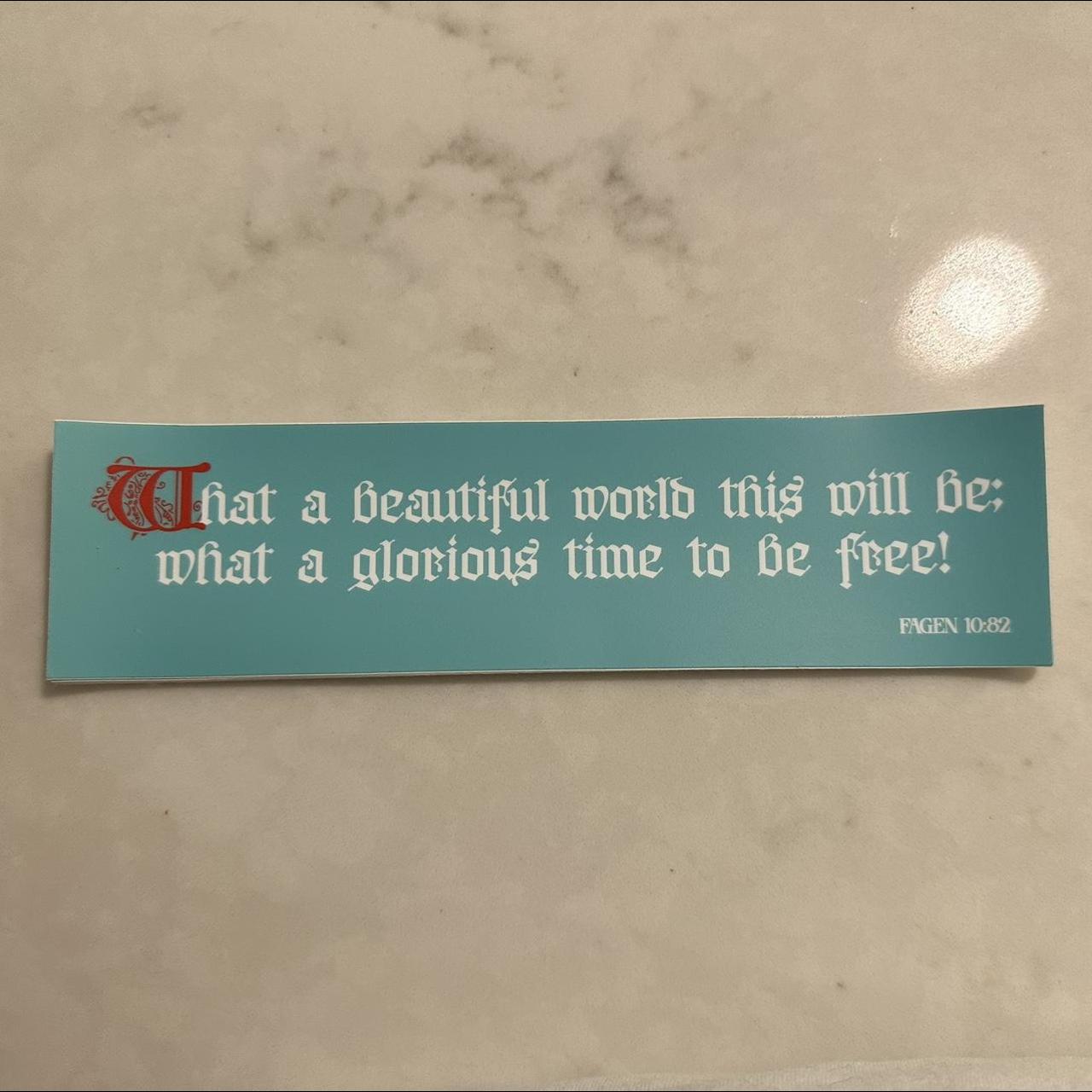

When he sings "What a beautiful world this will be / What a glorious time to be free," he’s singing from the perspective of a 1950s visionary who has no idea what’s coming. He’s singing about the world we were promised, not the one we actually got. By 1982, people knew that "machines to make big decisions" often meant nuclear targeting computers or bureaucratic nightmares. The undersea trains never happened. Instead, we got the crumbling infrastructure of the late 20th century.

Fagen is basically cosplaying as an optimist.

He’s looking back at his youth with a mix of genuine nostalgia and biting sarcasm. It’s a song about the innocence of belief. We really thought a "solar-powered city" would solve the human condition. We really thought that by 1976—the "big seventy-six" mentioned in the lyrics—everything would be different.

Key Themes in the Song:

- Technological Utopianism: The belief that science is a moral good that will eventually eliminate suffering.

- Lost Innocence: The transition from the collective hope of the 1950s to the individualist disillusionment of the 1980s.

- The Mid-Century Aesthetic: A sonic recreation of the "Googie" architecture and "Space Age" design movement.

The Cultural Impact of the International Geophysical Year

To understand why Fagen chose this specific event, you have to look at what the IGY actually was. 1957 was the year Sputnik 1 launched. It was the year of the first US Vanguard rocket attempt (which blew up on the pad, adding a layer of failure to the optimism). It was a moment of peak Cold War competition masked as scientific cooperation.

🔗 Read more: Songs by Tyler Childers: What Most People Get Wrong

The IGY was the ultimate "Big Science" project.

It involved sixty-seven countries. In the middle of the Cold War, the US and the USSR were actually sharing data about the Earth's magnetic field and the ionosphere. For a brief moment, it felt like the species was growing up.

Fagen’s choice of this subject isn't accidental. He’s a student of history and a lover of jazz, which itself is a music of precision and improvisation. The IGY represents the "organized" side of human nature—the part that builds rockets and charts the stars. I.G.Y. by Donald Fagen is the theme song for that ambition.

Why it Sounds "Expensive"

There is a reason why audiophiles still use The Nightfly to test speakers. The album was one of the first fully digital recordings. Fagen used the 3M 32-track digital system, which was cutting-edge and incredibly temperamental at the time.

The "expensive" sound comes from the sheer density of talent. Look at the credits. You have Larry Carlton on guitar. You have Greg Phillinganes on keyboards. These weren't just session guys; they were the elite.

The track doesn't have any "mud." Every frequency has its own space. The bass is lean and melodic, never overpowering the vocals. The percussion is varied, using everything from standard snares to more exotic, shimmering sounds that evoke the "sparkle" of the future.

Even the way the song fades out feels deliberate. It doesn't just end; it drifts away, like a satellite moving out of range.

Misconceptions About the Song

A lot of people think this is a Steely Dan song. It’s an easy mistake. It sounds like Steely Dan because Fagen is the sound of Steely Dan, alongside Walter Becker. But The Nightfly was his first solo outing, and it’s arguably more personal than anything the Dan ever put out.

💡 You might also like: Questions From Black Card Revoked: The Culture Test That Might Just Get You Roasted

Steely Dan songs are often about losers, junkies, and sleazebags. They are cynical to the bone.

I.G.Y. by Donald Fagen is different. It’s not about a person; it’s about a feeling. It’s about the collective psyche of a nation. It’s much more earnest, even if that earnestness is framed by a narrator who knows the dream didn't come true.

Another misconception is that it’s a pro-science anthem. It’s actually a song about the mythology of science. It’s about the stories we tell ourselves to feel better about the chaotic nature of the universe. Fagen isn't saying the scientists were wrong; he’s saying our expectations were wildly out of proportion with reality.

The Legacy of The Nightfly

When the album dropped, it was a massive success, but it also felt like an outlier. In a year dominated by Thriller and the rise of New Wave, Fagen was making high-concept, jazz-inflected pop about the 1950s.

It shouldn't have worked.

But it did. I.G.Y. by Donald Fagen hit the top 30 on the Billboard Hot 100. It became a staple of FM radio. More importantly, it became a cultural touchstone for "sophisti-pop."

The song has been sampled by everyone from rappers to electronic producers. Why? Because the groove is undeniable. Even if you don't care about the International Geophysical Year or the irony of 1950s futurism, the song makes you want to move. It has a rhythmic sophistication that is incredibly rare in pop music.

How to Appreciate the Song Today

If you want to really "get" the track, don't just stream it on crappy earbuds while you're at the gym.

- Find a high-quality source: At least a CD-quality FLAC or a clean vinyl pressing.

- Listen to the "sprawl": Pay attention to the background vocals during the chorus. Notice how they respond to the lead vocal.

- Focus on the lyrics: Read them like a short story. Imagine you are sitting in a kitchen in 1958, reading a magazine about the "House of the Future."

- Compare it to now: Think about our own "tech-optimism." We talk about AI and Mars colonies the same way Fagen's narrator talked about undersea trains. Are we any different?

Actionable Steps for the Fagen Fan

To truly dive into the world of I.G.Y. by Donald Fagen, you should expand your listening and reading habits to understand the context of its creation.

- Listen to the rest of The Nightfly: Tracks like "New Frontier" and "The Nightfly" continue the theme of late-fifties/early-sixties Americana. It is one of the few "perfect" albums where every track contributes to a unified concept.

- Read "Eminent Hipsters": This is Donald Fagen's book of essays. It provides a massive amount of insight into his influences, his upbringing, and his grumpy-yet-brilliant worldview. It helps explain why he writes the way he does.

- Explore the IGY archives: Look up the actual posters and newsreels from 1957. Seeing the visual aesthetic of the era makes the song’s sonic choices much clearer. The "International Geophysical Year" wasn't just a science project; it was a brand.

- Check out the 5.1 Surround Sound mix: If you have a home theater setup, the DVD-Audio or SACD versions of The Nightfly are legendary. It’s one of the best surround mixes ever created, allowing you to sit "inside" the arrangement.

The song is a reminder that the future is always shifting. What looks like a "glorious time to be free" today might look like a quaint, naive dream thirty years from now. Fagen captured that fleeting moment of hope and preserved it in digital amber. It’s brilliant, it’s biting, and it still sounds like it’s coming to us from a year that hasn't happened yet.