Most people think they know the story of the 1780 uprising in Peru. They picture a ragtag group of peasants wielding slingshots against cannons. They see it as a simple "Indians versus Spaniards" grudge match. Honestly, it was way more complicated than that.

The rebellion of Tupac Amaru II wasn't just a local riot; it was a massive, cross-cultural earthquake that nearly toppled the Spanish Empire in South America decades before Bolivar was even a household name. If you've ever wondered why the name "Tupac" carries so much weight—from the streets of Brooklyn to the peaks of the Andes—this is where it starts.

The Man Behind the Name

José Gabriel Condorcanqui wasn't some starving peasant living in a cave. He was a wealthy, Jesuit-educated businessman. He wore Spanish velvet, spoke fluent Latin, and owned a massive mule train that dominated the trade routes between Cusco and the silver mines of Potosí. Basically, he was part of the elite.

But he had a secret weapon: his bloodline.

José Gabriel claimed to be the direct descendant of the last Inca king, Tupac Amaru I, who the Spanish had executed in 1572. By the late 1770s, the Spanish "Bourbon Reforms" were squeezing everyone dry with new taxes and forced labor. José Gabriel had enough. He took the name Tupac Amaru II and decided it was time to reclaim the empire.

The Night Everything Changed

It all kicked off on November 4, 1780. There was a dinner party in Tinta, a small town south of Cusco. The guest of honor was Antonio de Arriaga, a Spanish district governor known for being particularly greedy and cruel.

Tupac Amaru II was there, too. He left early, waited in the shadows, and ambushed Arriaga on the road home.

📖 Related: Sweden School Shooting 2025: What Really Happened at Campus Risbergska

This wasn't a kidnapping for ransom. It was a trial. Tupac Amaru II forced Arriaga to write letters summoning other Spanish officials and demanding money. Six days later, in front of a massive crowd of indigenous people, mestizos, and even some nervous Spaniards, Arriaga was hanged.

The revolution had officially begun.

Micaela Bastidas: The Real Boss?

We talk about Tupac Amaru II, but we really need to talk about his wife, Micaela Bastidas.

Historians like Charles F. Walker have pointed out that Micaela was often more radical and a better strategist than her husband. While he was out in the field trying to convince people he was a king, she was back at headquarters in Tungasuca. She managed the money, recruited the soldiers, and ran a high-speed intelligence network using chasquis (messengers) on horseback.

She kept telling him to attack Cusco immediately. She knew the Spanish were disorganized. "I have warned you again and again," she wrote to him in a famous, scathing letter. He didn't listen. He hesitated, opting for a slower campaign.

That delay probably cost them the war.

👉 See also: Will Palestine Ever Be Free: What Most People Get Wrong

It Wasn't Just "Indigenous vs. Spanish"

This is the part that trips people up. The rebellion of Tupac Amaru II wasn't a race war—at least not at the start.

Tupac Amaru II actually tried to build a "multi-racial" coalition. He didn't hate the King of Spain (initially); he claimed he was fighting "bad government." He recruited:

- Indigenous peasants (the majority of his 60,000-strong army).

- Mestizos (mixed-race people).

- "Decent" Spaniards who were tired of high taxes.

- Enslaved Afro-Peruvians (he issued a decree of emancipation on November 16, 1780).

For a brief moment, it looked like a unified Peruvian identity was forming. But as the fighting got bloodier, the nuances vanished. The Spanish started massacring anyone with an indigenous face, and the rebels started killing anyone in Spanish clothes. The middle ground evaporated.

The Brutal End in the Plaza de Armas

By early 1781, the tide turned. The Spanish sent 17,000 troops from Lima. Betrayed by some of his own followers, Tupac Amaru II and his family were captured in April.

What happened next on May 18, 1781, is one of the darkest chapters in history.

In the main square of Cusco, the Spanish forced Tupac Amaru II to watch the execution of his wife, his eldest son Hipólito, and his closest advisors. The executioners cut out Micaela’s tongue before garroting her. Then, they tied the rebel leader’s limbs to four horses.

✨ Don't miss: JD Vance River Raised Controversy: What Really Happened in Ohio

The goal was to pull him apart.

It didn't work. His body was too strong. Frustrated, the executioners eventually just beheaded him. His youngest son, Fernando, who was only nine years old, was forced to watch the whole thing before being exiled to a Spanish prison for life.

Why This Still Matters in 2026

The rebellion didn't die with him. His cousins and surviving sons kept the fight going for another two years in the south, merging with the Aymara uprising of Tupac Katari. Roughly 100,000 people died in total.

The Spanish tried to "white-wash" history afterward. They banned the Quechua language, banned Inca clothing, and even tried to destroy the family trees of the nobility. They wanted to erase the very idea of an Inca return.

They failed.

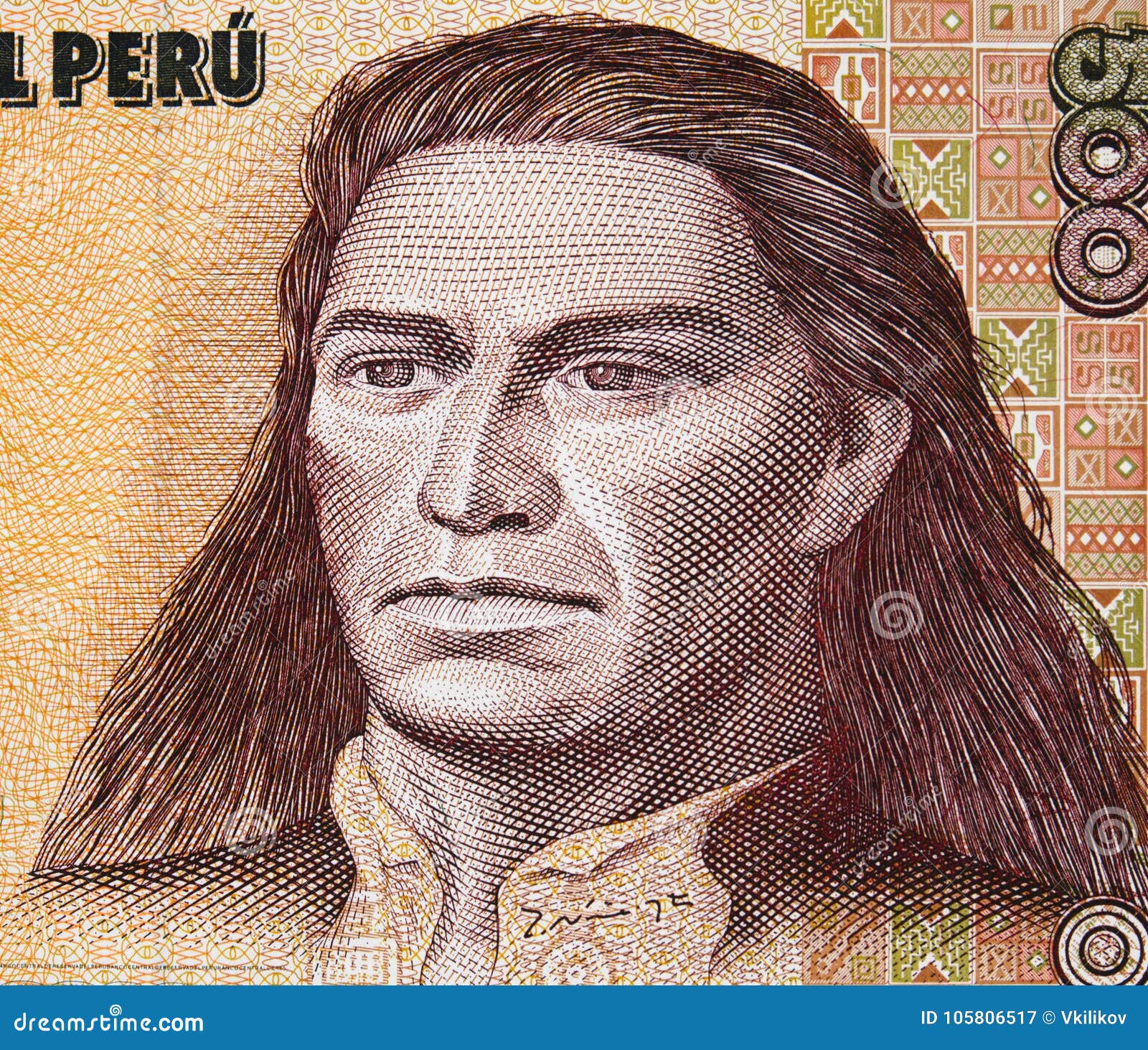

Today, Tupac Amaru II is a massive icon. He’s on the currency. He’s in the textbooks. Even the American rapper Tupac Shakur was named after him by his mother, Afeni Shakur, who wanted her son to carry the spirit of a revolutionary who fought for the oppressed.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

If you're looking to understand the real impact of this movement beyond the surface-level facts, here’s how to look at it:

- Look past the "Inca King" trope: Understand that this was an economic revolt triggered by the Bourbon Reforms. It wasn't just about ancient myths; it was about modern (at the time) taxes.

- Study the logistics: If you're a student of military history, look at Micaela Bastidas’ supply lines. She moved food and silver across the Andes without modern roads, which is a feat in itself.

- Acknowledge the fallout: The rebellion actually made some local elites more loyal to Spain because they were terrified of a social revolution from below. This is why Peru was one of the last places to gain independence in the 1820s.

To truly get the full picture, visit the Plaza de Armas in Cusco or the Museo de Sitio de la Casa de la Capitulación in Tinta. Seeing the physical locations where these events unfolded changes the way you view the "official" history books.