History likes to simplify people into cardboard cutouts. If you’ve ever looked into the American Revolution, you’ve probably seen the name William Legge, 2nd Earl of Dartmouth, tucked away in a dusty footnote about failed diplomacy. Most people just assume he was another stuffy British aristocrat who didn't "get" the colonies. That’s a mistake. Honestly, the guy was a walking contradiction—a deeply religious man known as "The Psalm-Singer" who somehow ended up as the Secretary of State for the Colonies right when the world started to burn.

Who Was the Real William Earl of Dartmouth?

William Legge wasn’t your average 18th-century power-broker. Born in 1731, he inherited the earldom from his grandfather and stepped into a world of immense privilege and even more immense pressure. You’ve got to understand the vibe of the time. The British Empire was expanding, but its soul was sort of rotting from the inside. While his peers were busy gambling at White’s or chasing scandals, Dartmouth was genuinely preoccupied with his faith. He was a prominent Methodist supporter, which, back then, was basically like being a radical outsider in the eyes of the Anglican elite.

He wasn't a warmonger. That’s the irony. When we talk about the Right Honorable William Earl of Dartmouth, we’re talking about a man who actually wanted to avoid the Revolutionary War. He was related to Lord North—his stepbrother, actually—which gave him a direct line to the heart of British power. But instead of using that to crush the Americans, he spent years trying to find a middle ground. He was the "pious Earl" who believed that if everyone just sat down and behaved like good Christians, the whole "taxation without representation" thing would just blow over. It didn't.

The Colonial Headache

Imagine being handed the keys to a department that’s already on fire. That was Dartmouth’s life in 1772. He took over the Colonial Office at a moment when the Bostonians were already itching for a fight. He replaced Lord Hillsborough, who was—to put it mildly—a jerk. The colonists actually liked Dartmouth at first. They thought, "Hey, here’s a guy who listens."

But listening isn't the same as acting. Dartmouth was stuck between a King who wouldn't budge and a colonial population that was done with compromise. He sent letters. So many letters. He tried to balance the legal rights of Parliament with the raw anger of the settlers. It’s kinda heartbreaking when you look at the primary sources. You see a man who is clearly out of his depth not because he’s stupid, but because he’s too decent for the cutthroat reality of 1770s politics.

✨ Don't miss: Franklin D Roosevelt Civil Rights Record: Why It Is Way More Complicated Than You Think

He didn't want the Boston Port Act. He didn't want the bloodshed at Lexington. Yet, because he stayed in office, his name is forever tied to the "Intolerable Acts." It's a classic case of a good man being the face of a bad system.

The Dartmouth College Connection

You can't talk about the Earl without mentioning the Ivy League. If the name sounds familiar and you aren't a history buff, it's because of Dartmouth College.

Here’s the weird part: he never actually went there. He never even set foot in New Hampshire.

The school’s founder, Eleazar Wheelock, was a savvy fundraiser. He knew Dartmouth was a big deal in the religious world and had a reputation for being generous with his wealth. Wheelock basically used the Earl’s name to give the school instant "street cred" and to secure funding from English benefactors. Dartmouth provided some initial support, mostly because he liked the idea of a school focused on Christianizing Native Americans. Later on, he actually got pretty annoyed with how the school was being run, but by then, the name had stuck.

🔗 Read more: 39 Carl St and Kevin Lau: What Actually Happened at the Cole Valley Property

- He was the primary patron who gave the school its prestige.

- The Earl’s personal library and papers still offer one of the best looks into the colonial mind.

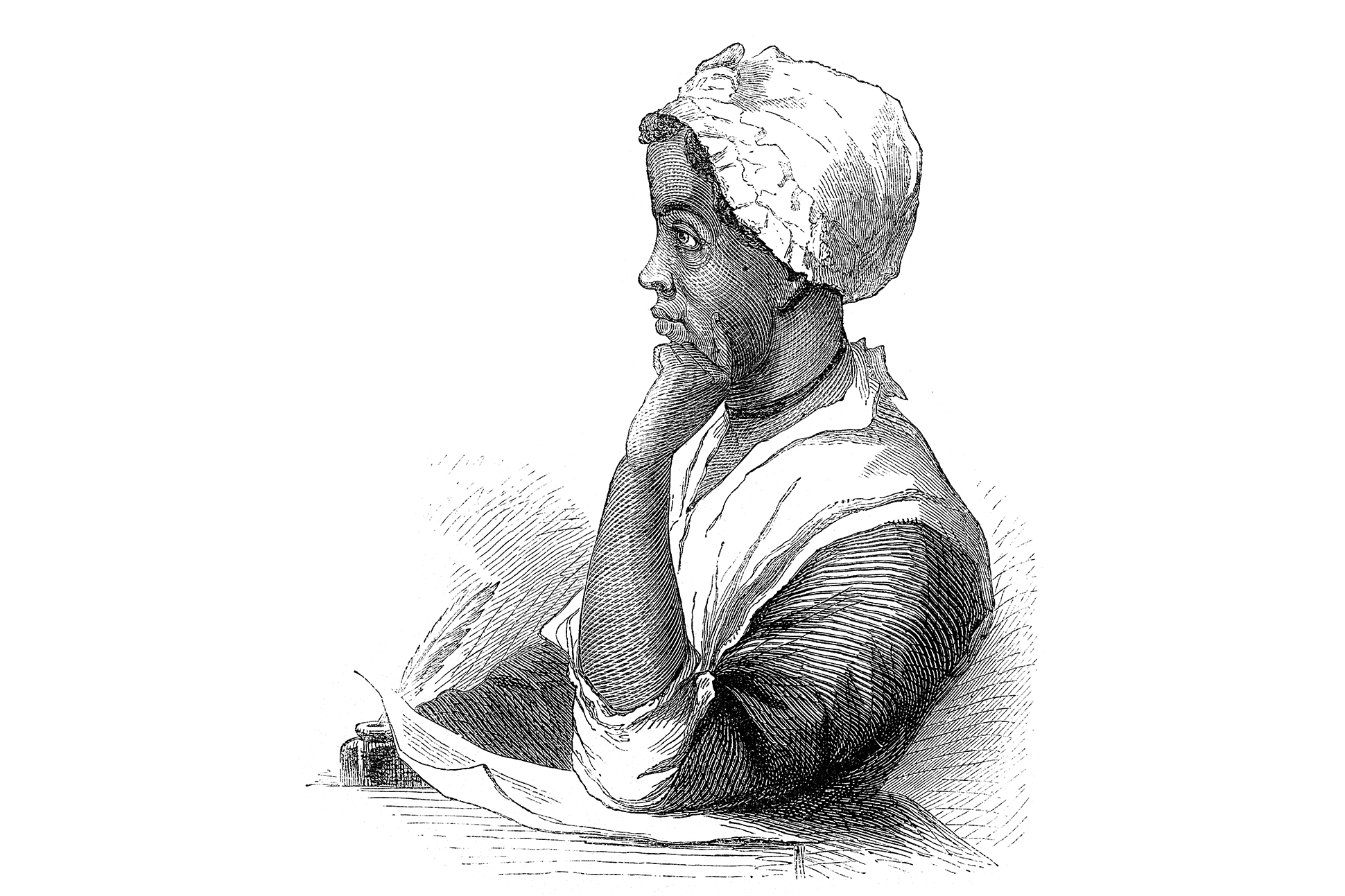

- His portrait still hangs at the college, a reminder of a British connection that survived the war.

The Tragedy of the "Olive Branch"

By 1775, things were falling apart. The Continental Congress sent over what we now call the "Olive Branch Petition." It was the last-ditch effort to avoid a full-scale war. And guess who it was addressed to? The Right Honorable William Earl of Dartmouth.

He received it. He read it. He probably prayed over it. But he couldn't get it to the King in a way that mattered. George III refused to even see the messengers. Dartmouth had to deliver the cold, hard "no" to the Americans. It’s one of those "what if" moments in history. If Dartmouth had been more aggressive with the King—or if the King had listened to his pious Secretary—the map of the world might look very different today.

Shortly after that, he resigned. He couldn't stomach the war. He moved to the position of Lord Privy Seal, effectively stepping away from the front lines of the American conflict. He spent his later years focused on his family and his faith, dying in 1801.

Why Nobody Talks About Him Properly

Modern history loves villains and heroes. Dartmouth doesn't fit either. He wasn't a tyrant like George III is often portrayed, and he wasn't a visionary like Jefferson. He was a bureaucrat with a conscience. That’s a boring headline for a textbook, but it’s the truth of how history actually moves. It moves through the hands of people who are trying their best and failing anyway.

💡 You might also like: Effingham County Jail Bookings 72 Hours: What Really Happened

We often forget that the British side wasn't a monolith. There were people in London—important people—who were absolutely sickened by the prospect of fighting their "American cousins." Dartmouth was the leader of that faction. When we ignore him, we ignore the complexity of the era. We treat the Revolution like a foregone conclusion instead of the messy, tragic divorce it actually was.

Assessing the Legacy of William Legge

If you’re looking for a takeaway, it’s that character matters, but circumstances often matter more. William Earl of Dartmouth was arguably the most moral man in the British cabinet, yet he presided over the greatest failure in the history of the British Empire.

His life is a lesson in the limits of "niceness" in politics. Being a "Psalm-Singer" didn't stop the cannons from firing. But his influence on education and his attempts at diplomacy provide a much-needed nuance to the story of 1776. He reminds us that even in the middle of a revolution, there were people on both sides trying to hold the world together with nothing but ink and prayer.

To really understand this period, you should stop looking at the battles and start looking at the correspondence. Look at the letters Dartmouth wrote to the colonial governors. You'll see a man desperate for a peace that the rest of the world had already given up on.

Next Steps for History Enthusiasts

If you want to go deeper into the life of the Earl of Dartmouth and the era he lived in, skip the generic history websites and go straight to the sources.

- Visit the Dartmouth College Digital Collections: They have digitized a significant amount of correspondence involving the Earl, especially concerning the founding of the college and his religious ties.

- Research the "Olive Branch Petition": Look specifically for the British response (or lack thereof) to see exactly how Dartmouth’s department handled the final attempt at peace.

- Explore Patshull Hall: Though it's changed hands many times, researching the Legge family seat in Staffordshire gives you a sense of the sheer scale of the world he came from.

- Read "The Pious Earl": Seek out academic papers or biographies that focus on the Methodist movement in 18th-century England to understand why his faith made him such an outlier in the government.