So, you want to know how to build a rail gun. It sounds like something straight out of Halo or a high-budget Navy test film where a metal slug obliterates a concrete wall at Mach 7. In reality, it’s a terrifyingly beautiful exercise in physics, specifically Lorentz forces, that usually ends with a lot of melted copper and a tripped circuit breaker.

You’ve probably seen those YouTube videos where a hobbyist tosses a few capacitors together and shoots a piece of aluminum through a soda can. It’s cool. It’s also incredibly dangerous if you don't respect the amperage. Building a functional electromagnetic projectile launcher isn't just about "rails" and "power"; it’s about managing massive energy discharge in microseconds without turning your project into a localized lightning strike.

The Basic Physics: Why This Stuff is Hard

A rail gun is fundamentally simple. You have two parallel conductive rails. You put a conductive projectile between them. You dump a massive amount of current through one rail, across the projectile, and back through the other rail. This creates a magnetic field that exerts a force—the Lorentz force—pushing the projectile forward.

✨ Don't miss: How to View Your YouTube Comments Without Getting Lost in the App

Mathematically, the force $F$ on the projectile is determined by the current $I$ and the inductance gradient of the rails $L'$, expressed as:

$$F = \frac{1}{2} L' I^2$$

Because the force is proportional to the square of the current, you need a lot of amps. We aren't talking about the 15 amps coming out of your wall. We are talking about tens of thousands of amps. This is where most DIY enthusiasts hit a wall. To get that kind of "oomph," you need a capacitor bank.

Managing the Power Source

Most people trying to learn how to build a rail gun start with capacitors. High-voltage electrolytic capacitors are the standard choice for hobbyists, though they are finicky. If you salvage them from old disposable cameras, you're playing a small game. If you buy a massive pulse-rated bank, you're playing a serious game.

Think about it this way. You need a way to store energy and then release it all at once. If the release is too slow, the projectile just heats up and welds itself to the rails. That’s called a "cold weld," and it’s the bane of every beginner's existence. You want a fast discharge. This requires a low Equivalent Series Resistance (ESR) in your capacitor bank.

Honestly, the wiring is where people mess up. You can't just use standard 12-gauge house wire. The skin effect and the sheer magnetic pressure of the current will literally whip the wires around or vaporize them. You need heavy copper busbars.

Materials and Rail Construction

The rails are usually copper or brass. Copper is better because it's more conductive, but it’s soft. Every time you fire the gun, a tiny bit of the rail surface vaporizes due to plasma arcing. This is called "rail ablation."

👉 See also: Mark Zuckerberg Trump Meeting: What Really Happened at Mar-a-Lago

- Rail Alignment: They must be perfectly parallel. If they diverge, the projectile loses contact and the circuit breaks. If they converge, the projectile jams.

- Containment: This is the part people forget. The magnetic fields generated by the rails actually want to push the rails apart. Without a heavy-duty frame—usually made of non-conductive, high-strength material like G10 fiberglass or thick polycarbonate—the rails will just explode outward during the first shot.

- The Armature: The projectile (armature) needs to be conductive. Aluminum is the gold standard for DIY because it’s light and has a low melting point, which actually helps form a plasma arc that maintains the connection between the rail and the slug.

The Problem with Arcing

When the projectile starts moving, it doesn't always stay in perfect physical contact with the copper. A plasma arc forms. This is good for conductivity but bad for the rails. It pits the metal. Professional setups, like the ones researched by BAE Systems for the U.S. Navy, used advanced alloys to survive more than a few shots. For a home build, expect to sand your rails after every single fire. It’s tedious. It’s messy. But it’s necessary if you want the next shot to actually leave the barrel.

Switching: The Dangerous Part

How do you "pull the trigger" on 400 volts and 20,000 amps? You can’t use a light switch. It would vaporize instantly. Most builds use a Silicon Controlled Rectifier (SCR) or a triggered spark gap.

SCRs are cleaner but can be easily fried by voltage spikes. A spark gap is basically two electrodes placed close together; when you want to fire, you ionize the air between them (often with a high-voltage pulse from a neon sign transformer), and the main capacitor bank dumps through the air. It’s loud. It smells like ozone. It’s very "mad scientist."

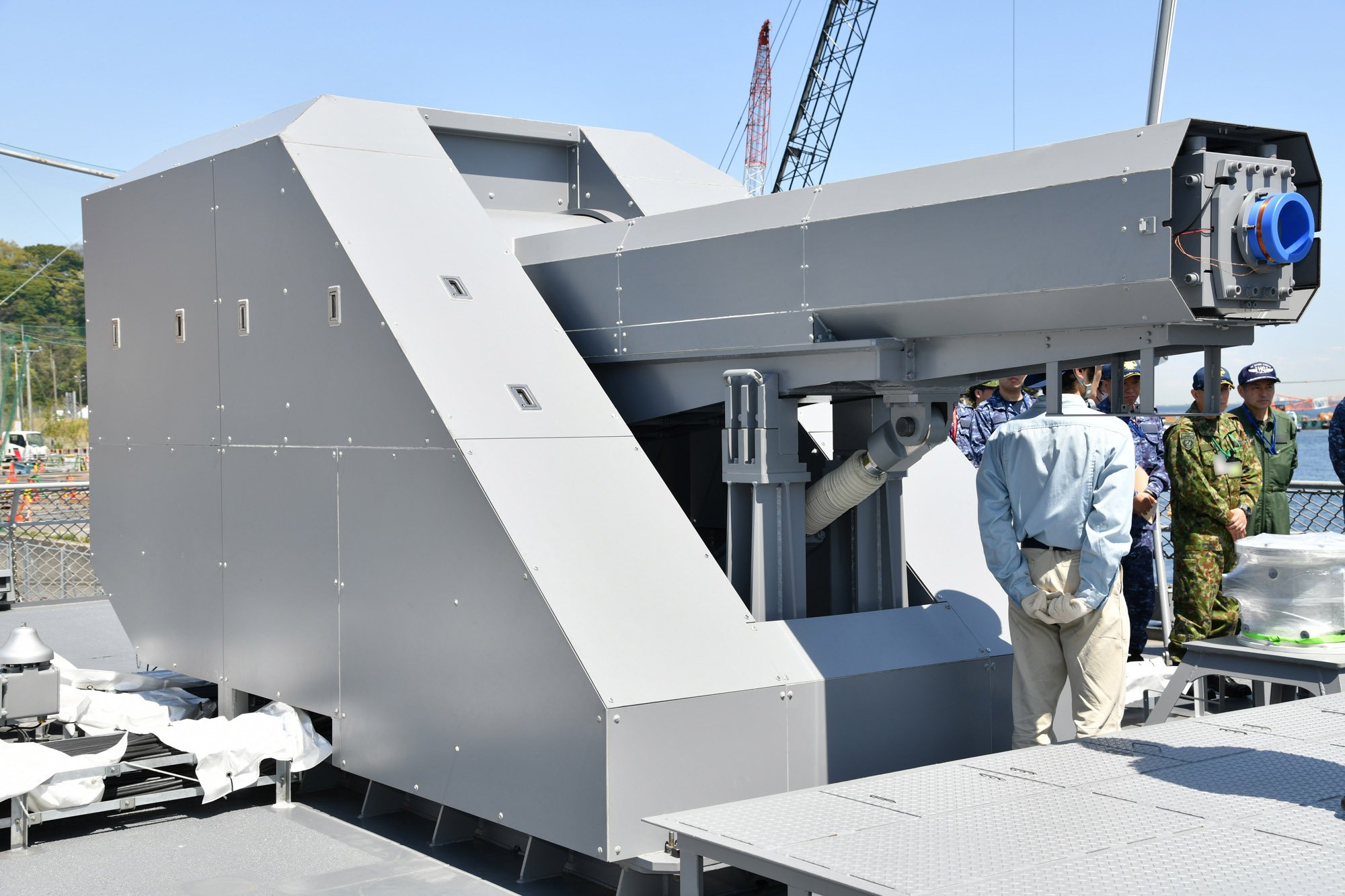

Why the Navy (Mostly) Gave Up

For a while, everyone thought rail guns were the future of naval warfare. The idea was to hit targets 100 miles away without using expensive missiles or volatile gunpowder. The U.S. Navy spent about $500 million over 15 years on this.

They ran into the same problems you will encounter on a smaller scale. The rails wore out too fast. The power requirements were so high that only a few ships (like the Zumwalt-class destroyers) could even provide the juice. By 2021, the Navy effectively paused the program to focus on hypersonic missiles. If the Pentagon struggled with rail longevity, don't feel bad if your DIY copper rails look like Swiss cheese after three shots.

Safety and Reality Checks

Let’s be real. How to build a rail gun is a question that leads to a lot of "don't try this at home" warnings for a reason. Capacitors can hold a lethal charge for days after being unplugged. If you touch the terminals of a charged bank, your heart stops. Period.

- Always use a bleed-down resistor to drain capacitors when not in use.

- Never work alone.

- Wear eye protection; plasma arcs throw molten copper bits at high speeds.

- Use a remote firing switch. You do not want to be standing next to the "breech" when a capacitor fails or a rail containment strap snaps.

Actionable Steps for the Aspiring Builder

If you are serious about experimenting with electromagnetic acceleration, don't start with a Mach 2 rail gun.

First, study Lenz’s Law and the Lorentz Force until you can visualize the magnetic fields. Then, build a small-scale coilgun (Gauss gun). Coilguns use magnets to pull a projectile rather than pushing current through it. They are significantly easier to build, more efficient at low energy levels, and don't involve the rail erosion that ruins most rail gun projects.

Once you understand capacitor charging circuits and SCR switching on a coilgun, then—and only then—should you look into the high-current busbar designs required for a rail gun. Check out resources like the PowerLabs archives or the 4hv forums, where high-voltage hobbyists have documented decades of failures and successes. Start small, use a multimeter religiously, and always, always discharge your caps before touching the rails.