If you’ve spent any time researching how to get your sight back after a diagnosis of Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD), you’ve probably seen the headlines about bionic eyes. They sound like sci-fi. Honestly, the idea of a tiny chip sliding into the back of your eye to replace dead photoreceptors is incredible, but the reality is way more nuanced than the "miracle cure" stories you see on the evening news.

Losing your central vision sucks. There’s no other way to put it. You can see the edges of the room, the frame of a doorway, or the shape of a tree, but the faces of your grandkids or the text in a book are just... gone. This happens because the macula, the high-resolution center of your retina, has basically given up. For years, if you had the "dry" version of AMD, doctors would just tell you to take some vitamins and buy a stronger magnifying glass. But the electronic eye implant for macular degeneration is changing that conversation, even if it’s not exactly a "new pair of eyes" just yet.

How these chips actually talk to your brain

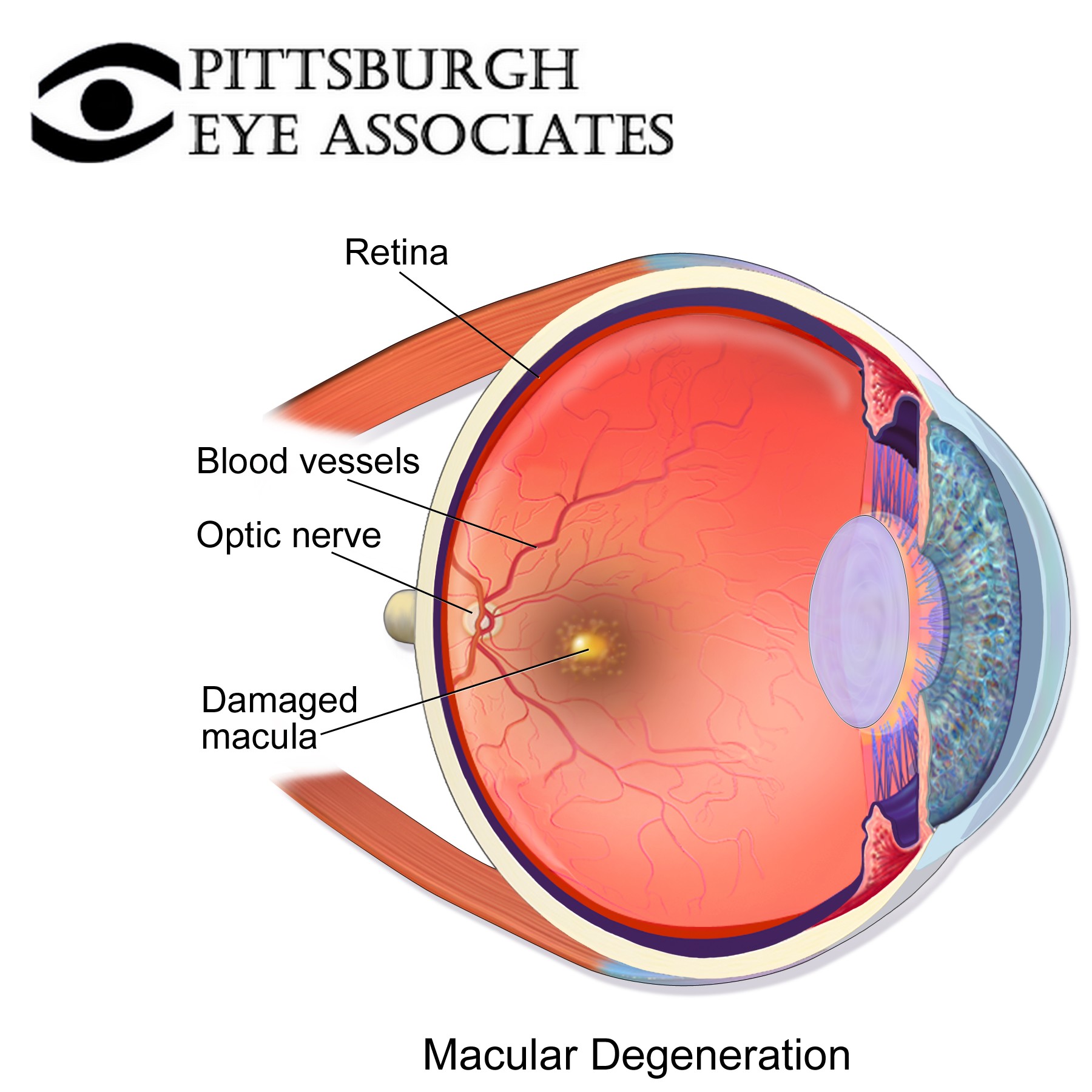

The retina is basically a biological circuit board. In a healthy eye, light hits cells called photoreceptors, which turn that light into electrical signals that travel up the optic nerve to the brain. In AMD, the wiring is mostly fine, but the "sensors" at the start of the chain are broken.

This is where things get cool.

Companies like Pixium Vision and Science Corp are developing subretinal implants that act as a bridge. Instead of trying to fix the dead cells, they bypass them. One of the most talked-about devices is the Prima System. It’s a tiny, wireless chip—about 2 millimeters square—that a surgeon places under the retina. You then wear a special pair of glasses equipped with a camera. Those glasses beam infrared light into your eye, hitting the chip, which then shocks the remaining healthy neurons into sending a signal to your brain.

It’s not perfect vision. Not even close.

👉 See also: Does Birth Control Pill Expire? What You Need to Know Before Taking an Old Pack

Patients often describe the "sight" as a series of flickering patterns or "phosphenes." Imagine a low-resolution LED scoreboard from the 1980s. You aren't seeing colors or fine textures. You're seeing shapes and contrast. For someone who has lived in a gray blur for a decade, though, being able to identify a doorway or a plate on a table is a massive deal.

The Prima System and the 2024 breakthroughs

We have to talk about the PRIMAVERA clinical trial results because they’re the most recent "big" thing in this space. Dr. Frank Holz and other researchers in Europe have been testing the Prima implant in patients with geographic atrophy (GA), which is the advanced stage of dry AMD.

The results were actually pretty wild. Some patients were able to read letters they couldn't see before. We aren't talking about War and Peace, but being able to recognize large print is a huge leap from total central blindness.

What’s interesting is that the brain has to "learn" how to see again. It’s not like flipping a light switch. You have to train your mind to interpret these weird electrical pulses. Some patients find it exhausting. Imagine trying to solve a puzzle where the pieces are made of light, and you have to do it every second of the day.

Why isn't everyone getting one?

There are some big hurdles. First, the surgery isn't a walk in the park. We’re talking about subretinal surgery, which carries risks like retinal detachment or infection.

✨ Don't miss: X Ray on Hand: What Your Doctor is Actually Looking For

Then there’s the hardware issue.

- Resolution: Current implants have a few hundred electrodes. Your natural eye has millions of photoreceptors. The math just doesn't add up to "normal" vision yet.

- Power: How do you power a chip inside an eyeball without a wire hanging out? Most systems use infrared light or induction, which is smart but limited.

- Regulatory Red Tape: The FDA and European regulators are (rightfully) cautious. These devices are still mostly in the "Investigational Device" phase.

There’s also the Argus II. You might have heard of it. It was the "gold standard" for a while, mostly for Retinitis Pigmentosa, but the company behind it, Second Sight, hit some major financial snags a few years back. It was a wake-up call for the industry. What happens if the company that made the computer in your head goes out of business? It’s a scary thought for patients who have hardware that might eventually need an update or a repair.

Science Corp and the "Science Eye"

A newer player that’s getting a lot of buzz is Science Corp, founded by Max Hodak (who used to be at Neuralink). They are working on something called the Science Eye.

Their approach is a bit different. They’re looking at a "flex-LED" display that sits on the retina, combined with optogenetics. This involves using gene therapy to make the remaining retinal cells sensitive to light, then using the implant to "drive" those cells. It sounds like something out of a Gibson novel. They’re aiming for much higher resolution than the older electrode-based chips.

The psychological toll of bionic sight

Nobody talks about the mental exhaustion.

🔗 Read more: Does Ginger Ale Help With Upset Stomach? Why Your Soda Habit Might Be Making Things Worse

When you get an electronic eye implant for macular degeneration, you aren't just a passive observer anymore. You are an operator of a piece of equipment. You have to adjust the contrast on your glasses. You have to scan your head back and forth because the camera's field of view is narrow.

I've read accounts from trial participants who say that while they value the device, they sometimes turn it off just to rest. The "vision" provided is artificial. It’s bright, it’s flickery, and it’s digital. It’s a tool for specific tasks—like finding a curb or reading a sign—rather than a way to "watch" a movie or enjoy a sunset.

What about the "Wet" vs "Dry" distinction?

Most of these implants are being designed for the Dry form of AMD. Why? Because in Wet AMD, you have leaky blood vessels and scarring that can physically mess with the placement of a chip. The Dry version, specifically Geographic Atrophy, leaves a "cleaner" area of dead cells where a chip can sit relatively undisturbed.

If you have Wet AMD, your current best bet is still the injections (like Eylea or Lucentis) to keep the swelling down. But as the tech improves, we might see chips that can handle scarred retinal environments too.

Practical Next Steps for Patients and Families

If you are looking into this for yourself or a parent, you need to be realistic. This isn't a consumer product you can buy at LensCrafters yet.

- Check ClinicalTrials.gov: This is the Bible for medical tech. Search for "Retinal Prosthesis" or "Subretinal Implant." If there’s a study happening near you, that’s your way in.

- Talk to a Retina Specialist, not just an Optometrist: You need someone who specializes in the back of the eye. Ask them specifically about the Prima System or Science Corp trials.

- Manage Expectations: Understand that "seeing" with an implant means seeing shapes and light patterns. It is about restoring independence, not restoring 20/20 vision.

- Look into Low-Vision Rehabilitation: Even without an implant, there are amazing high-tech goggles (like eSight or OrCam) that don't require surgery. They use cameras and screens to magnify what you see, and for many, they are a better intermediate step than surgery.

The technology is moving fast. We’ve gone from "totally impossible" to "low-resolution black and white" in a relatively short time. The electronic eye implant for macular degeneration is currently the frontier of ophthalmology. It’s a mix of heavy-duty surgery, clever engineering, and a lot of patience from the brave people volunteering for these trials.

We aren't at the "Geordi La Forge" visor stage yet, but for the first time in history, we’re actually on the path. The focus now is on increasing the number of electrodes—basically "upping the megapixels"—and making the surgery safer. Until then, keep an eye on the trial data and stay connected with a specialized retina clinic that follows these specific technological leaps.