When people ask what year was the Fugitive Slave Act, they usually expect a single date. History isn't that tidy. There were actually two of them, but when historians or history buffs talk about "The" Fugitive Slave Act, they are almost always pointing to 1850.

It was a brutal piece of legislation.

Honestly, it’s one of the most controversial laws ever passed in the United States. It didn’t just affect the South. It turned every single person in the North into a potential slave catcher, whether they liked it or not. Imagine living in Boston or Philadelphia and being legally forced to help a "slave hunter" kidnap your neighbor. That’s what happened.

The first version actually showed up in 1793. George Washington signed it. But it was kind of weak. Many Northern states just ignored it. They passed "Personal Liberty Laws" to protect Black people from being dragged South. By the time we get to 1850, the Southern states were furious. They demanded a law with teeth. They got it.

The Compromise of 1850 and the Law That Broke Everything

To understand what year was the Fugitive Slave Act written to its most extreme degree, you have to look at the mess of 1850. The United States was growing too fast for its own good. California wanted to be a free state. Texas was arguing about its borders. The South was threatening to leave the Union.

Enter Henry Clay and Daniel Webster. They tried to "save" the country with a massive political deal. California became free, and in exchange, the South got a revamped Fugitive Slave Act.

It was a deal with the devil.

This 1850 law was terrifyingly efficient. It created federal commissioners who had the power to decide if a person was a "runaway." There was no jury trial. The accused person couldn't even testify. Think about that for a second. You could be a free person, living your life, and someone could point a finger at you, and you weren't allowed to say a word in your own defense.

Even weirder? The commissioners got paid more to say "yes." If they ruled the person was a slave, they got $10. If they ruled the person was free, they only got $5. They claimed the extra $5 was for "paperwork," but it looked like a bribe. Because it was.

📖 Related: Weather Forecast Lockport NY: Why Today’s Snow Isn’t Just Hype

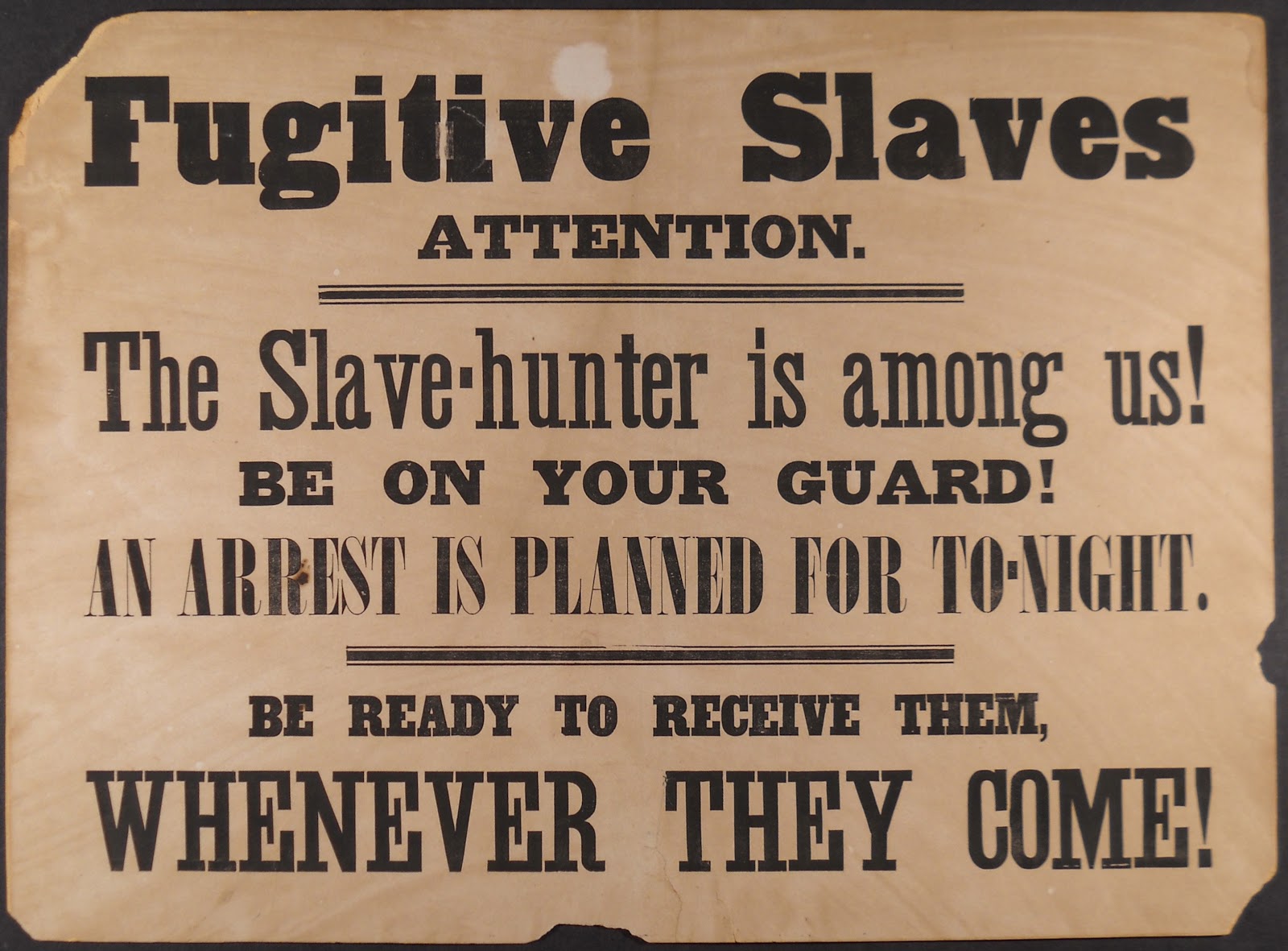

Resistance in the Streets: The North Wakes Up

This wasn't just a legal debate in a courtroom. It was a street fight.

Before 1850, a lot of people in the North were sort of "meh" about slavery. They didn't like it, but they figured it was a "Southern problem." The Fugitive Slave Act changed that instantly. Suddenly, the "Slave Power" was in their backyard.

You’ve probably heard of the Underground Railroad. It went into overdrive after 1850. People like Harriet Tubman weren't just helping people reach the North anymore; they had to get them all the way to Canada. The North wasn't safe.

In 1851, in Christiana, Pennsylvania, a group of Black men and women fought back against a Maryland slave owner named Edward Gorsuch. He had a federal warrant. They had guns. Gorsuch ended up dead. The government charged 38 people with treason, but they couldn't get a conviction. It was a mess.

Then there was Anthony Burns.

In 1854, federal troops had to march through the streets of Boston to return Burns to slavery. The city was in mourning. People hung black cloth from their windows. It cost the government roughly $40,000 to send one man back to Virginia. That’s hundreds of thousands in today's money.

Why the 1793 Act Failed

You might wonder why they needed a second law at all. The 1793 version was basically a "suggested guideline" by the time the 1840s rolled around.

The Supreme Court case Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842) basically said that while the federal law was valid, states didn't have to help enforce it. Northern states took that and ran with it. They pulled their police and judges out of the process. If a slave catcher came to town, he was on his own.

👉 See also: Economics Related News Articles: What the 2026 Headlines Actually Mean for Your Wallet

The 1850 law fixed that by making it a federal crime not to help. If a federal marshal asked for your help in capturing a runaway and you said no, you could go to jail.

The Cultural Explosion: Uncle Tom’s Cabin

You can't talk about what year was the Fugitive Slave Act without talking about Harriet Beecher Stowe.

She was living in Brunswick, Maine, when the law passed. She was so disgusted by it that she started writing. That turned into Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

It’s hard to overstate how big this book was. It was the 19th-century version of a viral sensation. It humanized the people being hunted. It made the Fugitive Slave Act feel like a personal attack on Christian values. When Abraham Lincoln met Stowe years later, he reportedly called her "the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war."

He wasn't really kidding.

The law was supposed to calm things down between the North and South. It did the exact opposite. It radicalized the North and made the South feel like the North was full of lawbreakers who wouldn't respect federal property rights.

The Legal Reality of 1850

Let's look at the actual mechanics of the law for a minute. It was designed to be impossible to beat.

- No Habeas Corpus: The standard right to be brought before a judge to see if your imprisonment is legal? Gone.

- Local Police Involvement: Federal marshals could deputize any citizen.

- Heavy Fines: Anyone harboring a runaway faced a $1,000 fine (a fortune then) and six months in prison.

It was a total overreach of federal power. Ironically, the South, which usually screamed about "states' rights," loved this federal intervention. The North, which usually liked a strong federal government, suddenly became the champion of states' rights to protect their citizens.

✨ Don't miss: Why a Man Hits Girl for Bullying Incidents Go Viral and What They Reveal About Our Breaking Point

Politics is funny like that.

What This Means for Us Today

Understanding what year was the Fugitive Slave Act isn't just about passing a history quiz. It's about seeing how laws can tear a country apart.

By the time 1860 rolled around, the Fugitive Slave Act had convinced most Northerners that slavery wasn't just a Southern institution—it was a national infection. It was the final straw. When South Carolina seceded, one of the main reasons they cited was that Northern states weren't following the Fugitive Slave Act.

It wasn't just about taxes or "territories." It was about the right to hunt human beings in free states.

Tangible Steps to Explore This Further

If you want to really get into the weeds of this era, don't just read a textbook. Textbooks are dry.

- Visit a National Park Site: Places like the African Meeting House in Boston or the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati have actual artifacts and primary sources from the 1850s.

- Read Primary Sources: Look up the "Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina." It mentions the failure of the Fugitive Slave Act explicitly. It’s eye-opening.

- Search Local Archives: If you live in the Northeast or the Midwest, there's a good chance your local town has records of "anti-man-hunting" committees formed specifically to fight the 1850 law.

- Track the Money: Research the "Commissions" records. Seeing the names of the men who were paid $10 to send people into bondage makes the history much more visceral.

The Fugitive Slave Act was finally repealed in June 1864, right in the middle of the Civil War. By then, the world it had helped create was already burning down.

Knowing the year—1850—is just the starting point. The real story is what happened in the streets afterward. It's a reminder that a law is only as strong as the people's willingness to follow it, and sometimes, a law is so unjust that "order" becomes the enemy of "justice."