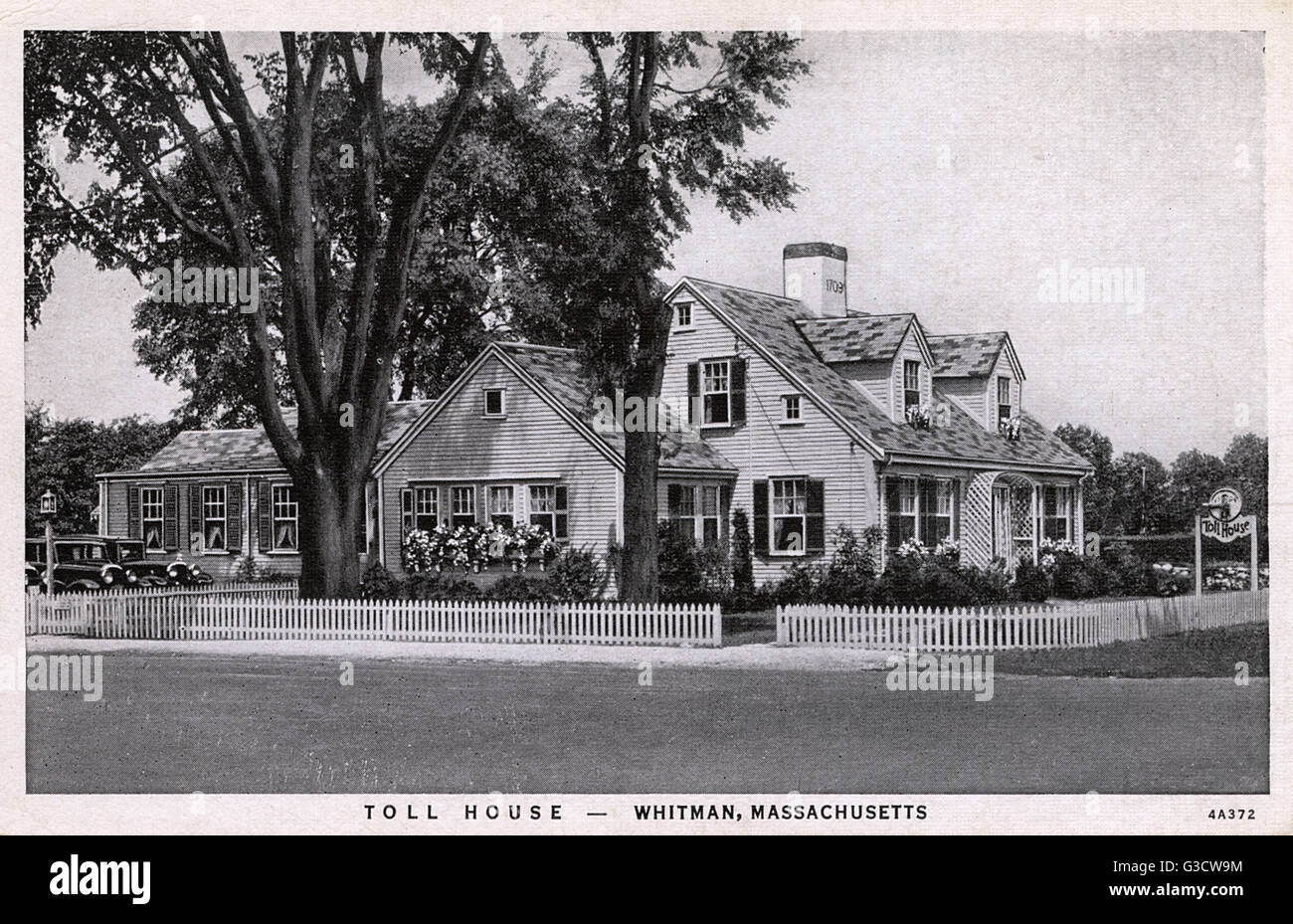

You’ve probably eaten a thousand chocolate chip cookies in your life. Most people have. But almost nobody realizes that the entire global obsession with that specific sugary treat traces back to one exact spot: a 1700s-era building on Bedford Street in Whitman, Massachusetts. It was called the Toll House Restaurant, and if you’re looking for it today, you won’t find it. A fire in 1984 saw to that.

It’s kinda wild to think that a single restaurant in a small New England town could dictate the dessert menu of the entire world.

Back in 1930, Ruth Graves Wakefield and her husband Kenneth bought an old house that used to be a place where travelers paid tolls and changed horses. They turned it into an inn. Ruth wasn't just some hobbyist cook; she was a dietitian and a graduate of the Framingham State Normal School Department of Household Arts. She was precise. She was professional. And honestly, she was a business genius before anyone used that term for chefs.

What Actually Happened at the Toll House Restaurant in Whitman

There is this persistent myth that the chocolate chip cookie was an accident. You’ve heard the story: Ruth was making chocolate cookies, ran out of baker's chocolate, chopped up a Nestlé semi-sweet bar, and figured it would melt and swirl into the dough. It didn't. The chunks stayed intact. Success by mistake.

Except, it’s basically nonsense.

Ruth Wakefield was a literal expert in food science. The idea that she didn't understand how chocolate behaves under heat is insulting to her legacy. In reality, she was a perfectionist who wanted to offer something different to her guests at the Toll House Restaurant. She deliberately developed the "Toll House Crunch Cookie" to be a balanced pairing with ice cream. She knew exactly what those chunks of chocolate would do.

The restaurant became a massive deal. We're talking about a place where people would drive for hours just to get a seat. It wasn't just about cookies, though that’s what we remember now. They served real, high-end New England comfort food. Think lobster, steaks, and thin-sliced "Toll House" potatoes.

💡 You might also like: Bootcut Pants for Men: Why the 70s Silhouette is Making a Massive Comeback

By the late 1930s, the recipe for the cookie appeared on the back of Nestlé chocolate bars. The deal Ruth made is legendary in the business world, though maybe not for the reasons you’d think. She didn't get royalties. She didn't get a percentage of every bag sold. She reportedly sold the rights to the recipe and the "Toll House" name to Nestlé for a grand total of one dollar—plus a lifetime supply of chocolate and a consulting gig.

Some people think she got ripped off. Others argue that the fame brought so much business to the Toll House Restaurant in Whitman that it was the greatest marketing move in history.

The Architecture and the Vibe of a Lost Landmark

If you walked into the Toll House back in the 40s or 50s, you weren't walking into a fast-food joint. It was classy. The building was a beautiful white colonial with dark shutters. Inside, it felt like someone's very wealthy, very tasteful grandmother’s dining room. There were multiple dining areas, like the "Colonial Room" and the "Garden Room."

Ruth insisted on excellence. The waitresses wore crisp uniforms. The tables were set perfectly. It was the kind of place where you dressed up.

But then, things changed. The Wakefields sold the business in 1966. The new owners tried to keep the magic alive, but it’s hard to capture lightning in a bottle twice. Then came New Year's Eve, 1984. A fire broke out. It started in the kitchen area—ironic, considering that kitchen changed American history—and it gutted the place.

The town of Whitman lost its most famous landmark in a matter of hours.

📖 Related: Bondage and Being Tied Up: A Realistic Look at Safety, Psychology, and Why People Do It

Today, if you drive to the site at 362 Bedford Street, you’ll see a Wendy’s. There’s a small historical marker. There’s a sign. But the physical soul of the Toll House Restaurant is gone. It's a bit depressing, honestly, to see a fast-food drive-thru standing where the world’s most famous cookie was born.

Why the Toll House Legacy Still Matters

You can still find "Toll House" style cookies everywhere, but the original recipe Ruth used had some specific quirks.

- She used a specific creamed butter technique that many modern commercial bakers skip.

- The original cookies were tiny—about the size of a half-dollar coin.

- They were meant to be crisp, not the doughy, underbaked "soft" cookies popular today.

If you want to experience the actual history, you have to look at the impact on Whitman itself. The town is still proud of it. There’s a "Toll House Park" nearby. But the real E-E-A-T (Experience, Expertise, Authoritativeness, and Trustworthiness) of this story lies in the culinary shift it caused. Before Ruth, "cookies" were usually fruit-based, nut-based, or plain sugar. She introduced the concept of the "morsel" as a primary flavor profile.

The Controversy of the "Accident" Narrative

Why does the "accident" story persist? Probably because people love a "eureka" moment. It makes for better TV. But if you look at Ruth's own cookbook, Toll House Tried and True Recipes, first published in 1930, you see the mind of a meticulous planner. She wasn't tripping into success. She was building a brand.

In fact, during WWII, soldiers from Massachusetts who were stationed overseas received Toll House cookies in care packages. They shared them with soldiers from other states. Soon, mothers and wives from all over the country were writing to the Wakefields asking for the recipe. That’s what truly turned a local Whitman restaurant into a global phenomenon.

It wasn't just a restaurant. It was a distribution hub for a new American culture.

👉 See also: Blue Tabby Maine Coon: What Most People Get Wrong About This Striking Coat

What You Should Do If You're a Food History Buff

Since you can't actually eat at the Toll House Restaurant in Whitman anymore, you have to be a bit of a detective to appreciate the history.

- Visit the Historical Marker: Go to the Wendy's parking lot in Whitman. It sounds silly, but standing on the actual ground where the oven sat is a weirdly powerful experience for foodies.

- Find an Original Cookbook: Look for vintage copies of Toll House Tried and True Recipes. The versions printed in the 1940s are the best because they contain the full menus of the restaurant, giving you a glimpse into what people were eating alongside their cookies.

- Bake the Original Recipe (Properly): Most people just follow the bag. To do it like Ruth, use high-quality butter, let your dough chill for at least 24 hours (a secret she swore by for flavor depth), and bake them until they are actually browned and crisp.

- Explore Whitman: The town has other historic spots, but the Toll House site remains the "North Star" for locals.

The Toll House Restaurant wasn't just a place to grab a bite. It was a massive engine of mid-century American hospitality. While the building is gone, every time you smell chocolate chip cookies in an oven, you're basically experiencing a ghost of Whitman, Massachusetts.

The real legacy isn't the dollar Nestlé paid her. It's the fact that Ruth Wakefield’s specific vision of a "crunchy tea snack" became the default comfort food for the entire planet. Not many chefs can claim they fundamentally changed the way a whole species eats dessert.

Actionable Next Steps

To truly honor the history of the Toll House Restaurant, stop buying the pre-made refrigerated dough for a minute. Buy the individual ingredients. Search for the "1930s Toll House original recipe" which often calls for a bit more salt and a longer creamed-butter stage than the modern "quick" versions. Pay attention to the texture. If it's not crisp and thin, it’s not an authentic Whitman Toll House cookie.