Biology class lied to you. Honestly, most of us grew up with a version of the egg and the sperm story that sounds more like a 1950s rom-com than actual science. The "dashing" sperm swims a marathon, fights through obstacles, and "conquers" the passive, waiting egg. It’s a great narrative if you’re writing a screenplay. For actual cellular biology? It’s basically fiction.

Scientists are finally catching up to a reality that is way more complex—and frankly, way cooler—than the old "survival of the fittest" race we were taught in middle school.

The Passive Egg Myth is Officially Dead

For decades, the scientific community described the egg as a dormant prize. It just sat there. It waited. In 1991, Emily Martin, an anthropologist at Johns Hopkins, wrote a now-famous paper called The Egg and the Sperm: How Science Has Constructed a Romance Based on Stereotypical Male-Female Roles. She pointed out that even researchers used words like "drifts" or "is transported" for the egg, while the sperm was "active," "strong," and "penetrating."

But here is the truth: the egg is the boss.

Recent research from places like Stockholm University and the Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust shows that eggs actually use chemical signals to "choose" which sperm they want. They aren't just sitting ducks. They are active gatekeepers. They release chemicals called chemoattractants that act like a scent trail. But here’s the kicker—the egg doesn’t just attract any sperm. It can actually prioritize sperm from specific partners over others, regardless of whose sperm is physically closest or fastest.

How the Sperm Actually Moves (It’s Not What You Think)

We’ve all seen the animation. The tail wiggles back and forth like a tadpole, right?

Nope.

💡 You might also like: Medicine Ball Set With Rack: What Your Home Gym Is Actually Missing

In 2020, researchers at the University of Bristol and the National Autonomous University of Mexico used 3D microscopy and high-speed cameras to see what’s really happening. It turns out sperm tails are wonky. They only stroke on one side. If they actually swam the way we thought, they’d just swim in circles until they died. To move forward, they have to roll while they swim, sort of like a spinning top or a corkscrew.

It’s less of a graceful Olympic sprint and more of a frantic, rotating struggle. They are basically "drilling" through the fluid, not gliding through it. This discovery was a massive deal because it changed how we look at male infertility. If the "roll" is off, the destination is never reached.

The Invisible Chemistry of the Egg and the Sperm

When we talk about the egg and the sperm, we usually focus on the moment of impact. But the "conversation" starts way earlier.

The female reproductive tract is actually a pretty hostile environment for sperm. It's acidic. It has an immune response. Out of the millions of sperm that start the journey, only a few thousand even make it to the fallopian tubes. This isn't just a "race" to see who is fastest; it's a brutal filtration process.

Chemical "Cheating" and Compatibility

Professor John Fitzpatrick from Stockholm University has done some incredible work on how eggs exert "mate choice" at a cellular level. His team found that follicular fluid (the nutrient-rich liquid surrounding the egg) attracts sperm from some men more than others.

Wait. It gets weirder.

📖 Related: Trump Says Don't Take Tylenol: Why This Medical Advice Is Stirring Controversy

This preference doesn't always match the person the woman actually chose as a partner. You could be deeply in love and compatible with your spouse, but your egg might technically "prefer" the chemical signature of a different person's sperm. This suggests that at a microscopic level, our bodies are looking for specific genetic compatibility—likely related to the Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC), which governs the immune system. The goal is to create offspring with the most diverse immune system possible.

The Moment of Fusion: A Mutual Handshake

Once the sperm actually reaches the egg, it’s not a "break-in." It’s more like a lock and key.

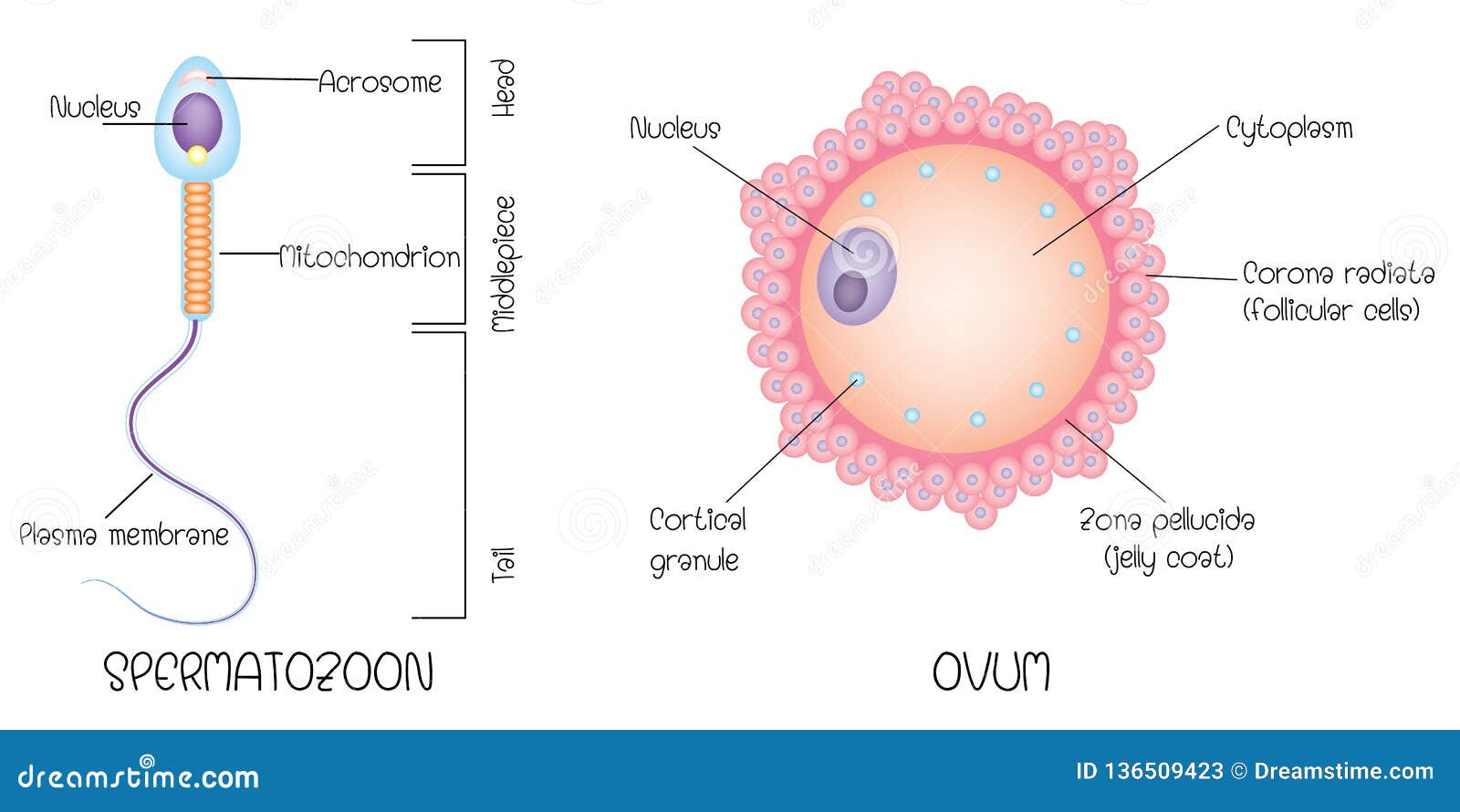

There are specific proteins involved here. On the sperm, there’s a protein called Izumo1 (named after a Japanese marriage shrine). On the egg, there’s a receptor called Juno (named after the Roman goddess of fertility).

- The sperm's Izumo1 meets the egg's Juno.

- They bind together.

- The egg's membrane basically "swallows" the sperm.

- Within seconds, the egg releases a burst of zinc—literally called a "zinc spark"—which hardens the outer shell (the zona pellucida) so no other sperm can get in.

If the egg was just a passive participant, this wouldn't work. The egg has to actively facilitate the fusion. Without the Juno receptor "grabbing" the Izumo1, the sperm could head-butt the egg all day and nothing would happen.

Misconceptions That Still Persist

We still hear people say that the "fastest" sperm wins. That’s almost never true.

The first sperm to arrive at the egg often spend their energy trying to break through the tough outer layers of the egg, essentially "softening" the target for the ones that arrive slightly later. The winner is often just the one that happened to be in the right place at the right time after the egg decided it was ready to open the door.

👉 See also: Why a boil in groin area female issues are more than just a pimple

Also, the idea that sperm are these rugged individualists is falling apart. Some studies suggest sperm might actually "clump" together to move more efficiently through cervical mucus, acting more like a team than a group of lone wolves.

Why This Science Actually Matters for You

Understanding the nuanced dance of the egg and the sperm isn't just for biology nerds. It has massive implications for IVF and fertility treatments. For a long time, if a couple couldn't conceive, doctors often looked at sperm "motility" (movement) and "count." But if the issue is actually the chemical signaling between a specific egg and a specific sperm, then just having "fast" sperm won't solve the problem.

We are moving toward a world of "personalized reproductive medicine." In the future, we might test for the chemical compatibility of follicular fluid and sperm before even attempting an IVF cycle.

Actionable Insights for Fertility and Health

If you are currently looking into reproductive health or just want to understand your body better, keep these points in mind:

- Sperm health isn't just about speed. Shape (morphology) and the ability to "roll" are just as vital. Lifestyle factors like heat exposure (laptops on laps, hot tubs) and smoking significantly impact the structural integrity of the sperm's "motor."

- The "Window" is about the environment. Since the egg is only viable for about 12-24 hours after ovulation, but sperm can live inside the female tract for up to 5 days, the "conversation" between the two often happens long before the egg is even released.

- Don't blame the "slow" ones. Modern research suggests that "slower" sperm might actually have more intact DNA, as they haven't exhausted their metabolic resources in a frantic sprint.

- Track the Signal. For those trying to conceive, focusing on cervical mucus is key because that mucus is the "highway" that facilitates the sperm's journey. If the mucus isn't the right consistency, the egg and sperm will never even meet, regardless of how "strong" they are.

The more we learn, the more we realize that reproduction isn't a conquest. It's a highly selective, chemically driven negotiation. The egg isn't waiting to be rescued, and the sperm isn't an invading army. They are two highly specialized cells performing a complex, molecular handshake that we are only just beginning to truly understand.