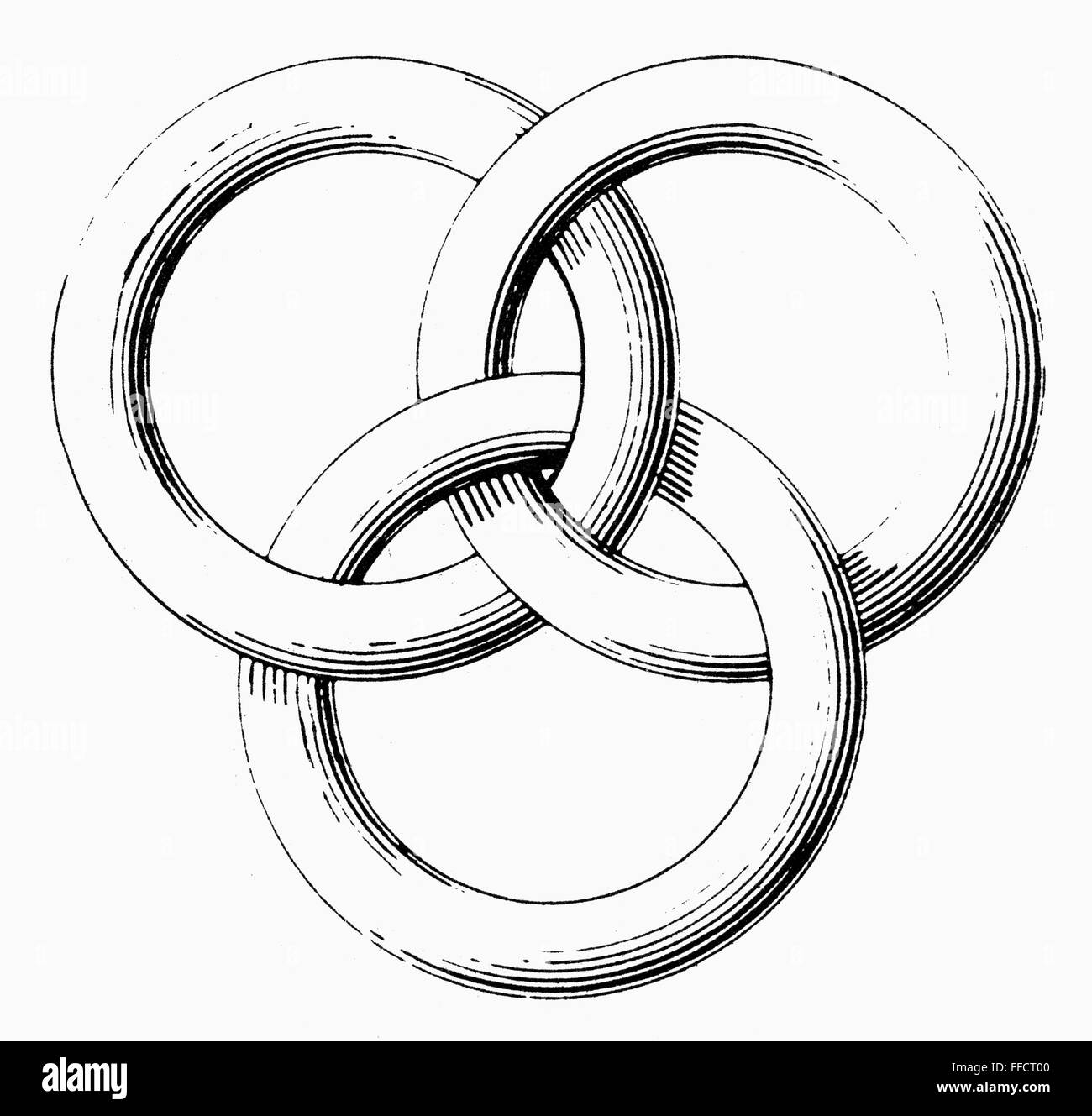

If you’ve ever looked at a modern beer can and wondered why there are three interlocking rings on it, you’ve met the ghost of P. Ballantine and Sons. It wasn’t just a brewery. For a solid century, it was the definition of American industrial might mixed with actual, honest-to-god brewing tradition. Most people today think "craft beer" started in California in the late 70s with Sierra Nevada or Anchor Steam. Honestly? They're wrong. Peter Ballantine was doing the heavy lifting in Newark, New Jersey, long before anyone cared about IBUs or dry-hopping.

Peter Ballantine was a Scottish immigrant who landed in Albany around 1830. He wasn't some corporate suit; he was a guy who understood malt. By 1840, he’d moved to Newark and started what would become an empire. It's wild to think that by 1950, P. Ballantine and Sons was the fourth-largest brewery in the entire United States. They were moving millions of barrels. But unlike the watery adjunct lagers that defined that era, Ballantine was famous for its Ale. That’s the distinction people forget. While everyone else was chasing the crisp, light pilsner trend, Ballantine stayed weird and stayed bitter.

The Three Rings and the Newark Powerhouse

You’ve seen the logo. Purity, Body, and Flavor. Legend says Peter Ballantine saw those wet rings left by a beer glass on a table and decided that was his brand. It’s a cool story, even if it feels a bit like 19th-century marketing fluff. But the logo worked. It became an icon of the Newark skyline. At its peak, the Newark brewery spanned over 40 acres. Imagine that. A massive, steaming, brick-and-iron city within a city, employing thousands of people and pumping out India Pale Ale that would actually stand up to the stuff we drink today.

The business side of P. Ballantine and Sons was fascinating because they were early adopters of basically everything. They didn't just make beer; they owned the distribution. They understood that if you control the trucks and the taverns, you control the market. During the 1940s and 50s, they were the "official beer" of the New York Yankees. Mel Allen, the legendary broadcaster, would call home runs "Ballantine Blasts." You couldn't escape the brand. It was the lifestyle beer of the Greatest Generation.

👉 See also: How Much Do Chick fil A Operators Make: What Most People Get Wrong

Why the IPA Was a Freak of Nature

Most beer historians, like the late Michael Jackson (the beer writer, not the singer), pointed to Ballantine India Pale Ale as the sole survivor of a lost era. During Prohibition, most breweries just died. The ones that lived did so by making "near beer" or ice cream. When the taps turned back on in 1933, the American palate had changed. People wanted light, easy, and cheap.

But P. Ballantine and Sons kept making their IPA.

This wasn't some weak 4% session ale. It was a beast. They aged it for a full year in massive wooden vats that were lined with brewers' pitch. This gave the beer a distinct, resinous, woody character that literally didn't exist anywhere else in the American market. It was hopped at a rate that would make a modern San Diego brewer nod in respect. If you were a beer geek in 1960, Ballantine IPA was your North Star. It was the only "real" ale left in a sea of fizzy yellow water.

✨ Don't miss: ROST Stock Price History: What Most People Get Wrong

The Slow, Painful Decline

So, what went wrong? How does the fourth-largest brewery in the country just... stop?

It was a perfect storm of bad timing and corporate shuffling. By the 1960s, the Ballantine family had stepped away, and the company was bought by the Investors Funding Corporation. Things got messy. Newark was changing. The labor costs were high, the equipment was aging, and the big midwestern brewers like Anheuser-Busch and Schlitz were using massive economies of scale to drive prices down. Ballantine couldn't compete on price, and they started messing with the recipes to save a buck.

That's the cardinal sin. Once you start cutting corners on the "Purity, Body, and Flavor," the brand is dead.

🔗 Read more: 53 Scott Ave Brooklyn NY: What It Actually Costs to Build a Creative Empire in East Williamsburg

In 1972, the Newark brewery finally shuddered. It was heartbreaking for the city. The brand was sold off to Falstaff Brewing Corporation, which eventually ended up in the hands of Pabst. For decades, Ballantine became a "zombie brand." It was still on shelves, but it wasn't the same beer. It was a budget label. The soul was gone. The Newark brewery was eventually demolished, and with it, a huge piece of American industrial history.

The Legacy That Refuses to Die

You can still find Ballantine Ale today, usually in the "cheap" section of a liquor store in the Northeast. It’s owned by Pabst Brewing Company now. A few years ago, Pabst actually tried to revive the original 19th-century IPA recipe. They did a decent job, honestly. They used dry hops and tried to mimic that woody, resinous punch. It wasn't exactly the same—mostly because you can't easily replicate year-long aging in 100-year-old wooden vats—but it was a noble effort.

The real legacy of P. Ballantine and Sons is the craft beer movement itself. Ken Grossman (Sierra Nevada) and Fritz Maytag (Anchor) have both spoken about the influence of those old-school East Coast ales. Ballantine proved that there was an audience for bitter, complex, high-alcohol beer in America, even when the "Big Three" were telling everyone that beer should taste like nothing.

Actionable Insights for the Beer Curious

If you want to actually experience the history of P. Ballantine and Sons without a time machine, here is what you need to do:

- Hunt for the Heritage: Look for the Pabst-owned Ballantine IPA "heritage" bottles. They aren't in every state, but they show up in New Jersey and New York. Compare it to a modern West Coast IPA. You'll notice the malt is much heavier—that's the Scottish influence.

- Study the Newark Map: If you're ever in Newark, look at the area around Ferry Street. The ghost of the brewery is still there in the architecture and the layout of the streets. It helps you realize the scale of what was lost.

- Read the Labels: Next time you see the three rings, remember they aren't just a design. They represent a specific brewing philosophy that predates the modern industry by 150 years.

- Support Local "Old School" Styles: If a local brewery makes a "Stock Ale" or a "Burton Ale," buy it. Those are the direct descendants of what Ballantine was trying to save.

P. Ballantine and Sons didn't fail because the beer was bad. It failed because it was an artisanal product trying to survive in a world that, for a few decades, only valued "fast and cheap." We’re lucky that the three rings survived at all, even if they're just a shadow of what they used to be. It’s a reminder that in the world of business, being the biggest and being the best are rarely the same thing.