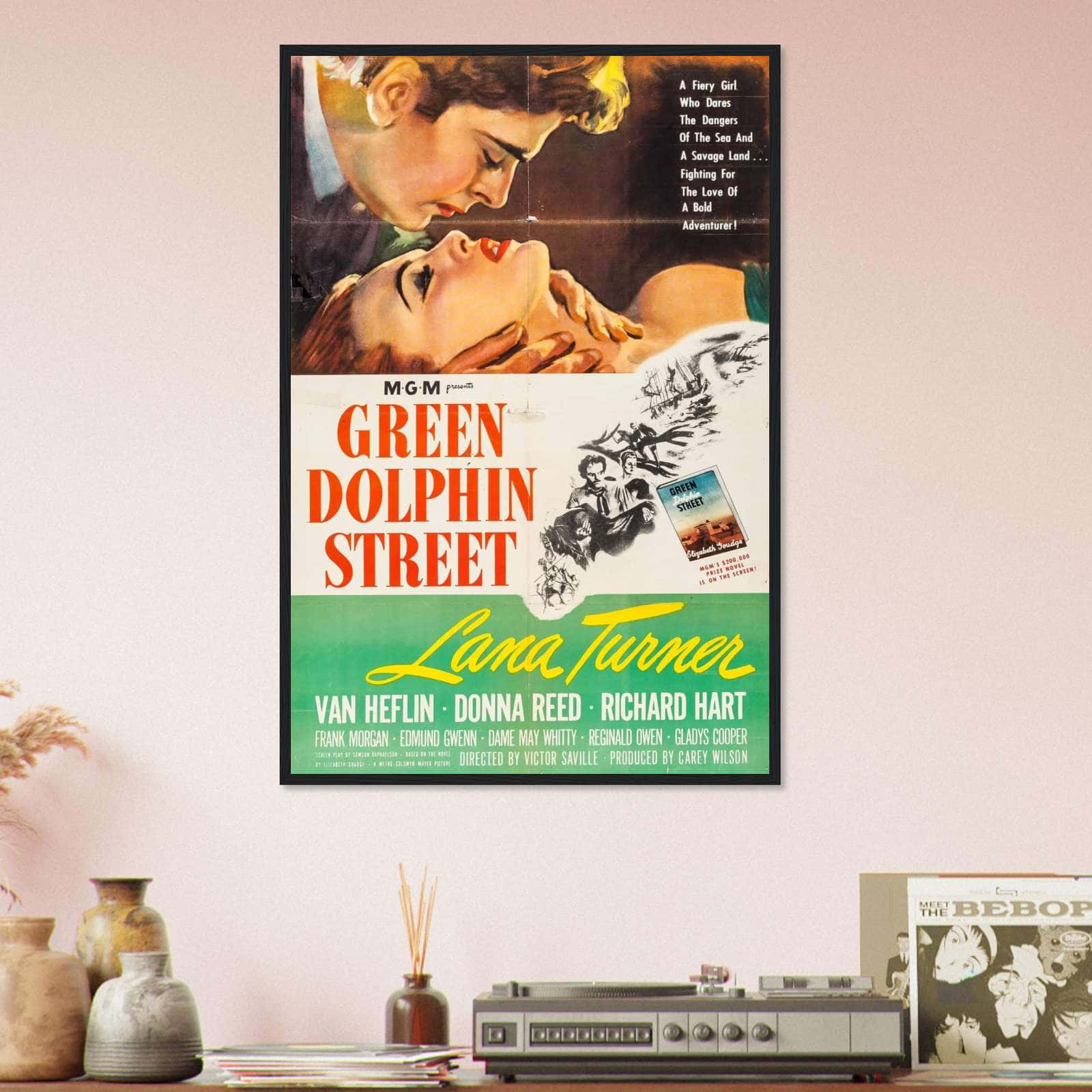

Big budgets usually mean big headaches. Honestly, if you look at the history of MGM, few movies prove that better than the 1947 release of Green Dolphin Street. It was a massive undertaking. A sprawling, earthquake-shaking, period-piece epic that cost the studio a fortune. Back then, $4 million wasn't just a high budget; it was astronomical. It was the kind of money that made studio executives sweat through their expensive suits.

People mostly remember it today for two things. First, that Oscar-winning earthquake sequence. Second, that incredibly famous jazz standard that shares its name. But there’s a lot more to the actual film than just special effects and a catchy tune.

Why Green Dolphin Street 1947 Actually Matters

It started with a contest. Elizabeth Goudge wrote the novel, which won the first-ever MGM Annual Novel Award. That wasn't a small prize; she took home $125,000. For 1944, that was a life-changing sum. MGM didn't just buy the rights; they bought a phenomenon. They wanted a story that felt as big as Gone with the Wind, but set in 19th-century New Zealand and the Channel Islands.

The plot is... well, it’s a mess of a mistake. Basically, you have two sisters, Marianne and Marguerite. They both love the same guy, William Ozanne. William, who is living in New Zealand, decides to write home and propose to one of them. The problem? He gets the names mixed up. He’s drunk or distracted—take your pick—and asks for the "wrong" sister.

It sounds like the plot of a modern sitcom. But in Green Dolphin Street 1947, it’s treated with the gravity of a Greek tragedy. Marianne, played by Lana Turner, makes the journey across the world to marry a man who was actually expecting her sister.

Lana Turner and the Star Power Problem

Lana Turner was at the height of her "Sweater Girl" fame, but she wanted to be a serious actress. This was her shot. She’s paired with Richard Hart and Donna Reed. Most people recognize Donna Reed from It’s a Wonderful Life, which came out just a year earlier. In this film, she’s the "wronged" sister who stays behind and eventually joins a convent.

✨ Don't miss: Why October London Make Me Wanna Is the Soul Revival We Actually Needed

Critics at the time were split. Some thought Turner was out of her depth in a period piece. Others were just distracted by the sheer scale of the production. The movie is long. It’s nearly two and a half hours. It moves slowly. Then, the earthquake happens.

That Earthquake: A Masterclass in 1940s Tech

If you watch the movie today, the drama might feel a bit stiff. The special effects, however, are still genuinely impressive. This was decades before CGI. To create the New Zealand earthquake and the subsequent tidal wave, the crew used massive hydraulic systems and miniature sets.

A. Arnold Gillespie, the legendary special effects chief at MGM, was the man behind the curtain. He had to make the earth literally split open. He used a combination of full-scale sets that could be tilted and broken, and incredibly detailed miniatures. It won the Academy Award for Best Special Effects for a reason. It’s the kind of practical filmmaking that feels "heavy" in a way modern digital effects rarely do. You can feel the weight of the rocks. You can see the real water crashing.

The Weird Legacy of the Theme Song

It’s kind of funny. If you ask a random person today about Green Dolphin Street 1947, they probably won't tell you about Lana Turner or the New Zealand Maori uprising featured in the film. They’ll start humming.

The song "On Green Dolphin Street," composed by Bronislau Kaper with lyrics by Ned Washington, became a massive jazz standard. It didn't happen immediately, though. It took about a decade. In 1958, Miles Davis recorded it for the 1958 Miles album. Then Bill Evans tackled it. Then Wynton Kelly.

🔗 Read more: How to Watch The Wolf and the Lion Without Getting Lost in the Wild

Suddenly, this theme from a somewhat bloated MGM melodrama became the "must-play" track for every serious jazz musician in New York and Chicago. It’s one of those rare cases where the music completely outlived the movie it was written for. Most people playing it in smoky jazz clubs today have probably never seen the film. They might not even know it’s about a guy who mailed a letter to the wrong girl.

Production Troubles and New Zealand

The film tried to capture the ruggedness of New Zealand, but most of it was shot in California. Santa Cruz and the Redwood forests stood in for the southern hemisphere. This was standard for 1947. Traveling a full crew to New Zealand was logistically impossible and wildly expensive.

The depiction of the Maori people is... let’s say "of its time." It’s a Hollywood version of history. It portrays the conflict through a very specific, colonial lens. For modern viewers, these scenes can be uncomfortable or just plain inaccurate. But as a historical artifact of how Hollywood viewed the world in the late 40s, it’s fascinating.

Is It Actually a Good Movie?

That depends on what you want. If you love the "Golden Age" style—where everything is lit perfectly and everyone speaks in mid-Atlantic accents—you’ll probably enjoy it. It’s a spectacle. It’s MGM doing what MGM did best: spending more money than anyone else to put "more stars than there are in the heavens" on screen.

However, the pacing is a slog. The central conceit—the mistaken identity in the letter—requires a massive suspension of disbelief. You have to believe that William would just "go with it" once Marianne arrived in New Zealand.

💡 You might also like: Is Lincoln Lawyer Coming Back? Mickey Haller's Next Move Explained

Yet, there is something moving about the ending. It’s about duty and making the best of a life you didn't necessarily choose. It’s a very 1940s sentiment. After the war, a lot of people were living lives they hadn't planned for. In that context, the story of Marianne and William probably hit home for audiences in a way it doesn't for us now.

Critical Reception and Box Office

Surprisingly, despite the mixed reviews from critics who called it "overlong" and "melodramatic," the public loved it. Green Dolphin Street 1947 was one of the highest-grossing films of the year. It proved that Lana Turner was a massive draw regardless of the genre.

It’s a reminder that what critics think often has very little to do with what the "paying public" wants to see on a Saturday night. They wanted escape. They wanted to see New Zealand (even if it was California). They wanted to see a tidal wave.

How to Watch It Today

Finding a high-quality version of Green Dolphin Street can be a bit of a hunt. It’s not always on the major streaming platforms like Netflix or Max. Usually, your best bet is Turner Classic Movies (TCM) or renting it through a boutique service.

If you decide to watch it, do it on the biggest screen possible. The earthquake sequence loses all its power on a phone screen. You need to see the scale of the sets to appreciate what Gillespie and his team pulled off.

Takeaway Steps for Film Buffs and Jazz Fans

- Listen to the evolution of the theme: Start with Bronislau Kaper’s original orchestral version from the 1947 soundtrack, then jump to the 1958 Miles Davis recording. Notice how Davis strips away the melodrama to find the cool, modal heart of the melody.

- Watch the earthquake sequence specifically: If you don't have time for the full 141 minutes, find the disaster sequence. Compare it to the earthquake in the 1936 film San Francisco. You can see exactly how MGM’s special effects department evolved in a decade.

- Read about the MGM Novel Award: It’s a weird piece of literary history. The contest was basically a way for the studio to "manufacture" bestsellers that they already owned the rights to. It was vertical integration at its most cynical—and most successful.

- Check out the 19th-century New Zealand setting: While the film is a Hollywood fantasy, it can be a gateway to learning about the real history of the New Zealand Wars (the Maori Wars) of the 1840s and 60s, which provide the backdrop for the story's climax.