Silicon Valley is full of "fake it till you make it" stories, but Elizabeth Holmes took that mantra to a level that literally put lives at risk. It wasn't just a corporate hustle. It was a obsession. When we talk about an inventor out for blood, we aren't usually being literal. With Holmes and her company, Theranos, the blood was the product, the currency, and eventually, the evidence that brought the whole house of cards down.

She was nineteen.

Dropping out of Stanford to change the world sounds like the standard tech bro origin story, right? But Holmes didn't want to build another app for food delivery or a social network for cats. She wanted to revolutionize healthcare by performing hundreds of medical tests—ranging from cholesterol checks to cancer detection—using just a single drop of blood from a finger prick.

It was a beautiful dream. It was also, as it turns out, a total fantasy.

The $9 Billion Mirage

At its peak, Theranos was valued at $9 billion. Think about that for a second. That is more than the GDP of some small countries, all built on a technology that didn't actually work. Holmes managed to convince some of the smartest, most powerful people in the world to join her board. We're talking George Shultz, Henry Kissinger, and James Mattis. These weren't tech-naive people, yet they fell for the black turtlenecks and the deep, modulated voice.

The machine was called the Edison.

It was supposed to be a miniature lab in a box. But inside the Theranos headquarters in Palo Alto, the reality was much grittier. The Edison failed. Constantly. It gave erratic results that would have been laughable if they weren't being used to make medical decisions. To cover it up, the company secretly used commercial, large-scale machines from companies like Siemens to run the tests they claimed were being done on their own "revolutionary" hardware.

They were basically diluting the tiny finger-prick samples just to make them large enough for the standard machines to read. It was a mess.

Why Nobody Saw It Coming

Honestly, the culture of secrecy was her greatest weapon.

🔗 Read more: Is Today a Holiday for the Stock Market? What You Need to Know Before the Opening Bell

Theranos didn't publish peer-reviewed studies. In the scientific community, that’s a massive red flag. Huge. If you’ve actually invented something that changes the laws of physics or biology, you show your work. Holmes didn't. She claimed it was "trade secrets."

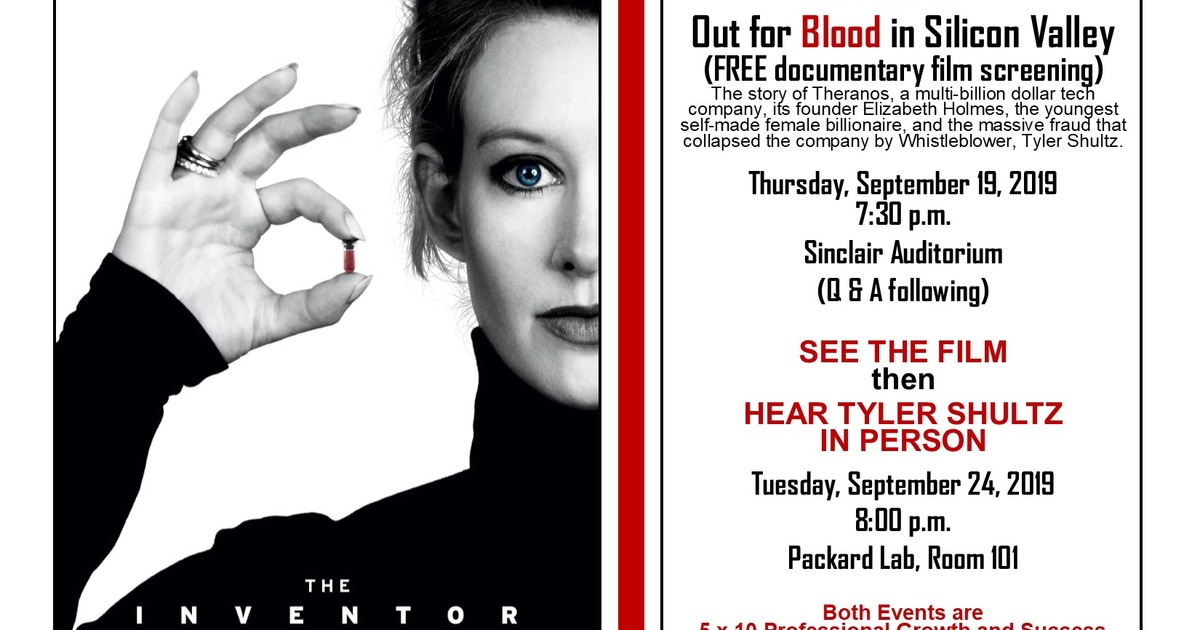

If you were an employee who asked too many questions, you were gone. Security guards followed people to their cars. Non-disclosure agreements were used like cudgels. Tyler Shultz, the grandson of board member George Shultz, was one of the first to really see the rot from the inside. He realized the quality control tests were being manipulated. When he tried to speak up, his own family ties couldn't protect him from the company's high-priced lawyers, including the legendary David Boies.

The legal pressure was immense. It was a David vs. Goliath situation, except Goliath had a billion-dollar war chest and a fleet of private investigators.

The Inventor Out for Blood and the Wall Street Journal

Everything changed because of a guy named John Carreyrou.

He was a reporter at the Wall Street Journal who got a tip that something wasn't right. What followed was a masterclass in investigative journalism. Holmes and her partner, Sunny Balwani, tried everything to kill the story. They went to Rupert Murdoch—who had invested $125 million in Theranos—to try and get him to spike the article.

Murdoch refused. He told them he trusted his editors.

When the first article dropped in October 2015, the facade started to crumble. The FDA began investigating. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) conducted a surprise inspection of the Theranos lab and found conditions that were "inflicting immediate jeopardy to patient health and safety."

People were getting results that said they were having miscarriages when they weren't. Others were told their blood sugar was fine when it was dangerously high. This wasn't just white-collar fraud; it was a public health crisis.

💡 You might also like: Olin Corporation Stock Price: What Most People Get Wrong

The Psychological Profile of a Visionary

Was she a con artist from day one? It’s complicated.

Most experts, including those who have studied her extensively like Carreyrou or the makers of the The Dropout, suggest she likely started with a genuine desire to innovate. She had a phobia of needles. She wanted to make blood testing easier. But somewhere along the line, the gap between her ambition and the reality of the science became a chasm.

Instead of admitting defeat or pivoting, she doubled down on the lie.

There's this thing in Silicon Valley called "visionary gaslighting." You convince yourself so thoroughly of the future you're building that the present-day lies don't feel like lies anymore. They just feel like "unrealized truths."

Lessons for the Modern Tech Landscape

We see echoes of this today. Whether it’s in the crypto space or the rush for Artificial Intelligence, the pressure to deliver "the next big thing" often outpaces the actual development of the technology.

Investors are often more afraid of missing out (FOMO) than they are of losing money. That’s how you end up with a board of directors that doesn't include a single person with a medical degree for a blood-testing company.

Nuance matters.

Science isn't like software. You can't just "patch" a biological error in a later update. Biology is messy, stubborn, and doesn't care about your marketing deck. The Theranos saga serves as a permanent warning that in fields where human lives are on the line, "disruption" needs to be backed by data, not just charisma.

📖 Related: Funny Team Work Images: Why Your Office Slack Channel Is Obsessed With Them

What Actually Happened in Court

The legal fallout was a long time coming.

In 2022, Elizabeth Holmes was convicted on four counts of defrauding investors. She was sentenced to more than 11 years in prison. Sunny Balwani got even more. During the trial, Holmes tried a variety of defenses, including alleging abuse by Balwani and claiming she simply didn't understand the technical failures of her own company.

The jury didn't buy it.

They saw the emails. They heard the recordings. They saw an inventor out for blood—specifically, the money of investors like the DeVos family and the Waltons—who was willing to sacrifice everything to maintain her status as the world’s youngest self-made female billionaire.

Actionable Insights for Investors and Founders

If you're looking at the next "revolutionary" startup, or if you're building one yourself, here are the takeaways that actually matter in a post-Theranos world:

- Demand the Data: If a company refuses to show peer-reviewed data or third-party validation under the guise of "proprietary secrets," walk away. Genuine innovation survives scrutiny.

- Check the Board's Expertise: A board should match the company’s mission. A biotech company needs doctors and scientists on the board, not just former Secretaries of State.

- Culture is a Leading Indicator: High turnover, extreme secrecy, and the use of legal threats against employees are almost always signs of a toxic core.

- The "Too Good to be True" Rule: If a technology claims to bypass the fundamental laws of its field (like fitting a massive lab into a tiny box without compromising accuracy), it probably hasn't.

The story of Theranos is finally over, but the impulse that created it—the desire to believe in a miracle worker—is still very much alive. Staying skeptical isn't being a hater; it's being responsible.

Verify the claims. Talk to the whistleblowers. Never let a turtleneck distract you from the spreadsheet. If you're a founder, remember that your reputation is built on what your product does, not what you say it will do in five years. Precision in science and honesty in business aren't optional extras; they are the foundation. When those fail, the whole structure eventually comes down, no matter how much venture capital you pour into the cracks.