It wasn't a secret lab in a sci-fi movie. It was a cold, slightly damp shed in Scotland. On July 5, 1996, a lamb was born that basically broke the internet before the internet was even a thing. Her name was Dolly the sheep, and she wasn't just another farm animal. She was the first mammal ever cloned from an adult cell.

People lost their minds.

The media went into a frenzy. There were headlines about "playing God" and "the end of humanity as we know it." But if you talk to the scientists who were actually there at the Roslin Institute—guys like Ian Wilmut and Keith Campbell—the vibe was a bit different. It was more about a grueling, repetitive process of trial and error that finally, miraculously, worked.

Before Dolly, everyone thought specialized cells were a one-way street. Once a cell decided it was a skin cell or a heart cell, that was it. No going back. Dolly proved that theory was garbage. You could actually "reprogram" a cell's DNA to start over from scratch. That realization changed medicine forever, even if we don't have cloned mammoths roaming our backyards yet.

How Cloning Dolly the Sheep Actually Worked (No, It Wasn't Magic)

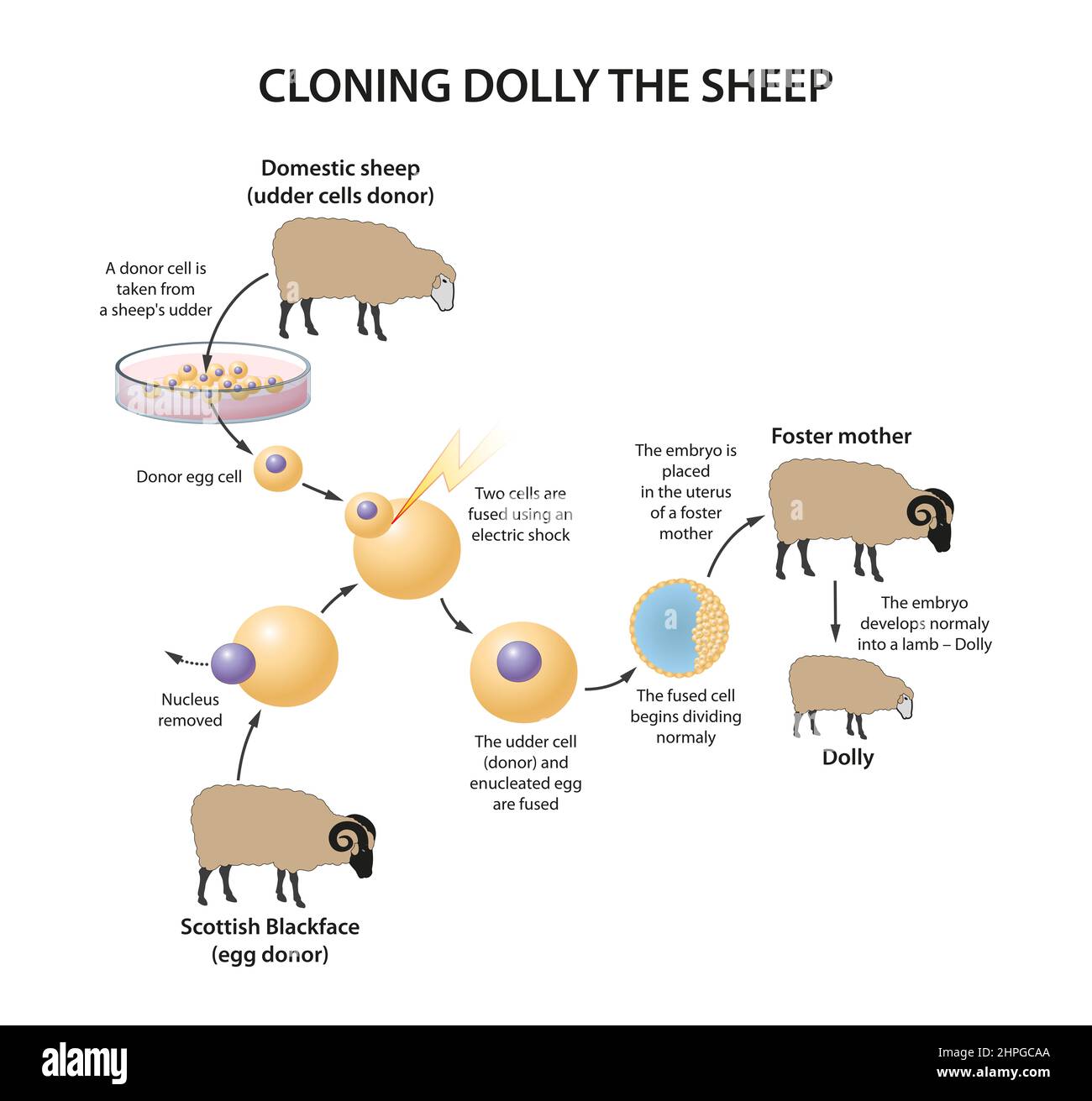

Most people think cloning is like a Xerox machine. You put a sheep in, press a button, and another one pops out. Honestly, it’s way more tedious and prone to failure than that. The team used a technique called Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer (SCNT).

Here is the breakdown of what really happened in that lab.

💡 You might also like: How Big is 70 Inches? What Most People Get Wrong Before Buying

They took a cell from the mammary gland of a six-year-old Finn Dorset ewe. That's actually why they named her Dolly—a cheeky, somewhat questionable reference to Dolly Parton. They took the nucleus out of that cell. Then, they took an egg cell from a different sheep (a Scottish Blackface) and removed its nucleus.

They used a tiny pulse of electricity to fuse the adult nucleus into the empty egg. It's like jump-starting a car. This "reset" the DNA. Out of 277 attempts, only one resulted in a live birth. One. That’s a 0.3% success rate.

If you’re wondering why Dolly looked like a white-faced Finn Dorset instead of her black-faced surrogate mother, that’s the DNA at work. She was a genetic twin of a sheep that had been dead for years by the time Dolly was even born.

The Controversy and the "Old Sheep" Myth

When Dolly died at age six, the world jumped to conclusions. She was euthanized on February 14, 2003, because she had a progressive lung disease and pretty severe arthritis. Immediately, the "cloning causes premature aging" narrative took over.

People argued that because she was cloned from a six-year-old sheep, her biological clock was already ticking. They pointed to her telomeres—the protective caps on the ends of chromosomes that shorten as we age. Dolly’s telomeres were indeed shorter than normal.

📖 Related: Texas Internet Outage: Why Your Connection is Down and When It's Coming Back

But here’s the thing: she lived indoors for her own protection. Most sheep live outside and get plenty of exercise. Dolly was treated like a royal, but she was also sedentary. The lung disease she caught, Jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus, is actually super common in sheep kept indoors. Later studies on other cloned sheep (the "Nottingham Dollies") showed they aged pretty normally.

So, did cloning kill her early? Probably not. It was likely a mix of bad luck and a very pampered, indoor lifestyle.

Why We Aren't Cloning Humans (Yet)

Ethically, it's a nightmare. Technically, it’s even worse.

After Dolly, the world waited for the first human clone. It hasn't happened. At least, not a full-grown person. In 2005, researchers in South Korea claimed they had cloned human embryos, but it turned out to be a massive case of scientific fraud.

Human biology is finicky. The SCNT process that worked for cloning Dolly the sheep is incredibly inefficient in primates. There are "epigenetic" errors—basically, the DNA doesn't always "unfold" correctly when it's reset. This leads to miscarriages, organ failure, and developmental issues.

👉 See also: Why the Star Trek Flip Phone Still Defines How We Think About Gadgets

Besides, what would be the point? A clone isn't a "respawn" of a person. They wouldn't have your memories or your personality. They’d just be a younger twin born in a different time.

What Dolly actually gave us:

- Stem Cell Research: Dolly paved the way for iPSCs (induced pluripotent stem cells). We can now turn skin cells into "blank slate" cells without needing embryos.

- Gene Editing: We can now "edit" livestock to be resistant to diseases, like the bird flu.

- Drug Production: Scientists have cloned animals that produce specific proteins in their milk used to treat human blood clots.

The Legacy Nobody Talks About

We talk about the science, but we rarely talk about the culture. Dolly was a celebrity. She appeared in Time magazine. She had her own fan mail.

But her existence forced governments to actually sit down and write laws about biotechnology. Before 1996, the "Wild West" of genetics was mostly theoretical. Dolly made it real. Presidents and Prime Ministers had to decide where the line was.

She's currently stuffed and on display at the Royal Museum of Scotland. She looks like a normal sheep. You wouldn't know she changed the course of human history just by looking at her.

What You Should Do Now

If you're fascinated by the ethics or the science of where we are now, don't stop at the 90s. The world of genetics has moved light-years beyond Dolly.

- Look into CRISPR: This is the current "gold standard" for gene editing. It’s faster, cheaper, and more precise than the cloning methods used in the 90s.

- Follow "De-extinction" Projects: Companies like Colossal Biosciences are currently trying to bring back the Woolly Mammoth and the Dodo using tech that started with Dolly.

- Read the Original Paper: If you're a nerd for details, look up the 1997 paper in Nature titled "Viable offspring derived from fetal and adult mammalian cells." It’s dense, but it’s the blueprint for the modern age.

The era of Dolly might be over, but the era of "reprogramming" life is just getting started. Understanding how she happened is the first step to understanding where we're going next.