You’ve seen it on coffee mugs. It’s plastered across protest signs every time there’s a political dust-up. Most people know the rhythm of the lines—the haunting progression from "they came for the socialists" to "they came for me." But honestly, most of the ways we quote they came for me and i said nothing are actually wrong. We’ve turned a messy, guilt-ridden confession of a man who once supported the Nazis into a generic slogan about "standing up for what’s right."

The truth is way more uncomfortable.

It wasn’t written as an inspirational quote. It was a confession. Martin Niemöller, the German pastor who authored the poem (which is actually a prose confession), wasn't some lifelong hero of the resistance. For a long time, he was exactly the opposite. That’s why the words have such a bite. He wasn't talking about "them" out there; he was talking about the failure of "us."

Who was Martin Niemöller anyway?

Niemöller was a complicated guy. He was a U-boat commander in World War I. He was a nationalist. At first, he actually welcomed Hitler’s rise because he thought it would bring a "national revival" to Germany. It's a bit jarring to think about, right? The guy who wrote the world's most famous poem about the dangers of silence was, for several years, a supporter of the very regime he eventually warned us about.

He didn't start speaking out because he was a radical progressive. He started speaking out because the Nazis began interfering in the church.

It was a slow burn.

By the time he realized the full scale of the horror, it was late. He was arrested in 1937 and spent seven years in concentration camps, including Sachsenhausen and Dachau. He survived, but he spent the rest of his life haunted. He realized that his silence—and the silence of the Protestant church—had paved the way for the Holocaust.

What the poem actually says (and why it varies)

If you look for the "official" version of they came for me and i said nothing, you won’t find one. That’s because Niemöller didn’t write it down as a poem in a study. He spoke it. He said different versions of it in different speeches throughout the late 1940s.

📖 Related: Why Fox Has a Problem: The Identity Crisis at the Top of Cable News

Usually, it goes something like this:

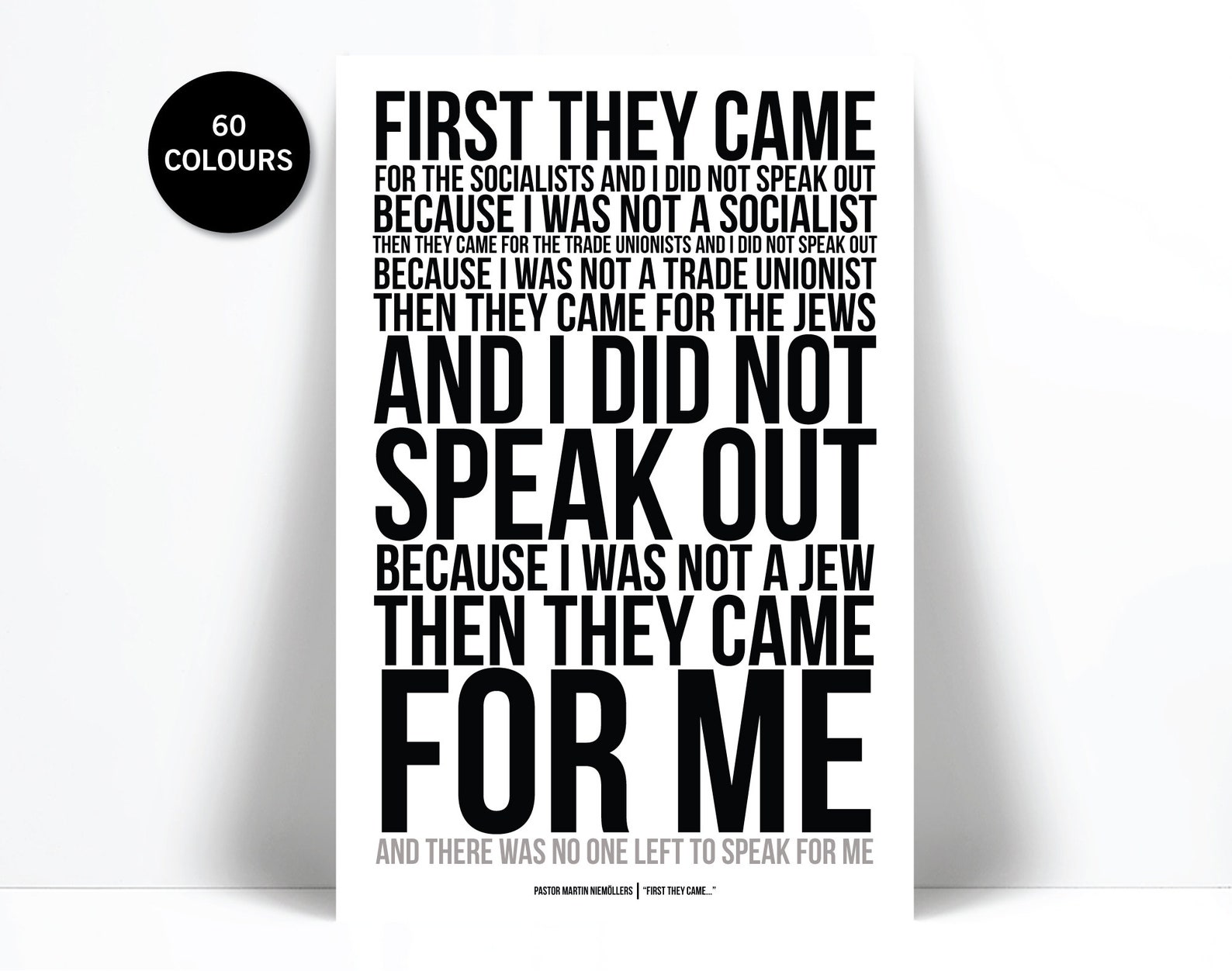

First, they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a socialist. Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a trade unionist. Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out—because I was not a Jew. Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.

Sometimes he included Communists. Sometimes he included the "incurably ill," a reference to the T4 Euthanasia program. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum uses a specific version, but the core message never changes. It’s about the "salami tactic" of authoritarianism. You slice away one group. Then another. Then another. Nobody screams because the blade isn't touching them yet.

Why we keep getting it wrong

We like to use the poem to feel morally superior. We post it on social media to tell other people why they should care about our specific cause. But Niemöller wasn't trying to give us a weapon to use against our neighbors. He was trying to give us a mirror.

When he said they came for me and i said nothing, he was admitting to his own anti-Semitism. That’s the part people skip over in the history books. Early in his career, Niemöller held views that were typical of the German right-wing at the time. He didn't initially speak up for the Jews not because he "forgot," but because he didn't think it was his problem.

He had to go through the fire of the camps to realize that human rights aren't divisible. If you don't defend the person you dislike, you lose the right to be defended yourself.

The psychology of silence

Why do people stay quiet? It's not always cowardice. Sometimes it's just "bystander effect" on a massive, national scale.

👉 See also: The CIA Stars on the Wall: What the Memorial Really Represents

Psychologists often point to something called pluralistic ignorance. Basically, you look around and see no one else is reacting, so you assume everything is probably fine. Or you think, "I'm just one person, what can I do?"

In Nazi Germany, this was amplified by genuine terror. But Niemöller's point was that the terror only became possible because of the initial apathy. By the time the Gestapo is knocking on your door, the "speaking out" phase of the timeline is long gone. The time to speak was years earlier, when the "socialists" or the "unionists" were being targeted.

Why it’s trending again in 2026

We live in a hyper-polarized world. It’s very easy to stay silent when "the other side" gets cancelled, de-platformed, or targeted by legislation. We think, "Well, I'm not one of them, so it doesn't affect me."

But the logic of they came for me and i said nothing is a mathematical certainty. If the standard for state or social overreach is "it's okay as long as it's happening to people I don't like," eventually the circle of "people I like" shrinks until you’re the only one left inside it.

We see this in digital rights, in surveillance culture, and in the way modern political movements operate.

Lessons that actually matter

If you want to move beyond the quote and actually live the lesson, it takes more than a tweet. It takes a weird kind of bravery to defend the rights of someone whose guts you absolutely hate.

If you only support free speech for people you agree with, you don't actually support free speech. You support your own echo chamber.

✨ Don't miss: Passive Resistance Explained: Why It Is Way More Than Just Standing Still

Niemöller’s confession is a reminder that the "me" in the poem is the final victim of a process the "me" helped start through inaction.

Watch the margins. Authoritarianism never starts with the majority. It starts with the people the majority is already annoyed with. If you see a group being dehumanized—even a group you disagree with—that is the "first" group.

Check your own apathy. Are you staying silent because you’re afraid, or because you’re comfortable? Comfort is usually a bigger killer of democracy than fear.

Understand the "Salami Effect." Recognize when rights are being eroded bit by bit. It’s never one giant leap; it’s a thousand tiny steps.

Speak when it’s socially awkward. Real "speaking out" usually happens at dinner tables or in office meetings before it ever happens at a rally.

The weight of they came for me and i said nothing isn't in the tragedy of the ending. It’s in the missed opportunities of the beginning. It’s a call to be the person who speaks up for the "socialist" or the "Jew" or the "outsider" while you still have a voice to use.

Don't wait until the room is empty. By then, the silence is just an echo of your own mistakes.

The most important thing you can do today is look at who is currently being "marginalized" in your own circles. Ask yourself: if they were gone tomorrow, would you feel safer, or would you just be next? History suggests the latter.