In 1973, a high school English teacher named Bruce Severy in Drake, North Dakota, decided to assign Slaughterhouse-Five to his students. It didn't go well. The local school board didn't just disagree with the curriculum; they gathered up 32 copies of Kurt Vonnegut's masterpiece and burned them in the school's furnace. Literally. They incinerated the books like it was a scene out of Fahrenheit 451. When Vonnegut found out, he didn't just call his lawyer or write a snarky tweet—mostly because Twitter didn't exist, but also because he had something better: a typewriter and a bone-deep sense of indignation. He sat down and wrote a letter that eventually became known by its most haunting line, I am very real, a phrase that has since echoed through decades of censorship battles.

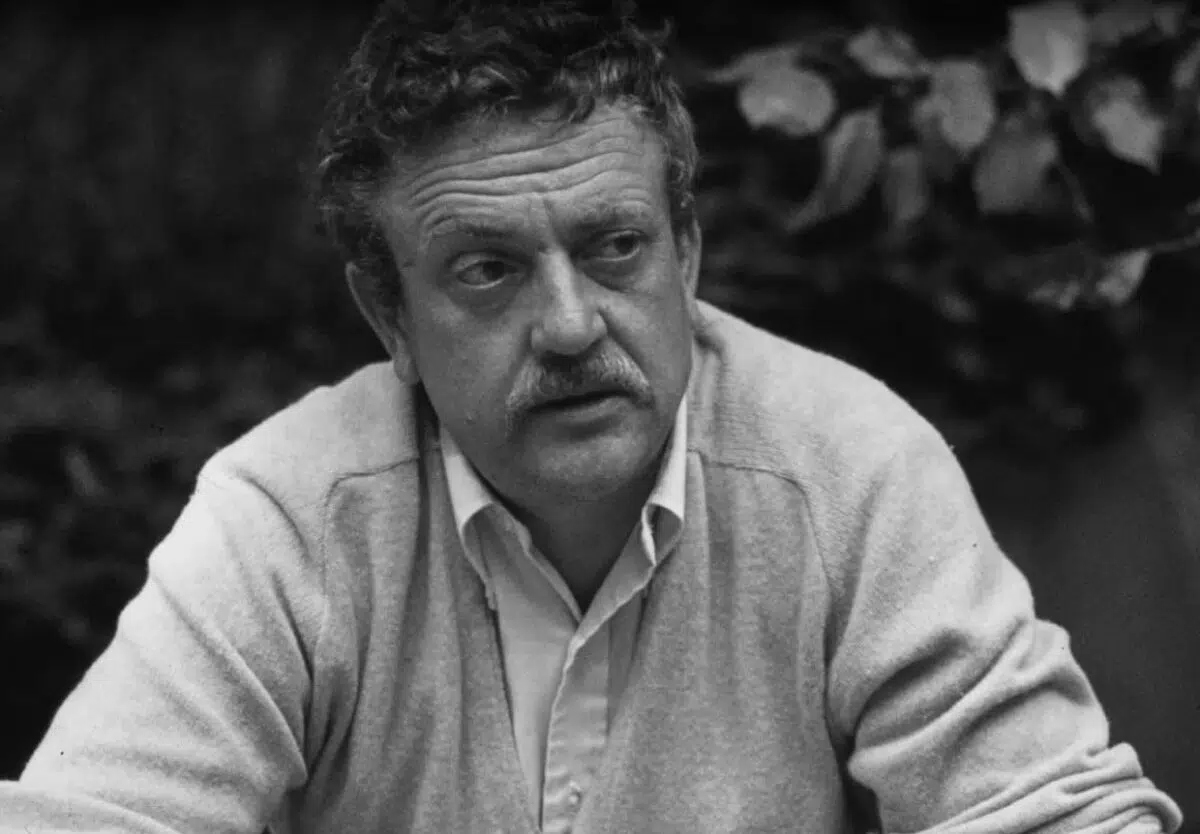

It’s a weirdly personal letter. You’d expect a famous author to be detached or maybe even slightly arrogant about their success, but Vonnegut sounds like a guy whose feelings were genuinely hurt. He was an American citizen, a combat veteran, and a father. He wasn't some "filthy" influence from the big city. He was a human being.

What actually happened in Drake, North Dakota?

People tend to forget how visceral this was. This wasn't a "polite" removal of books from a library shelf. The school board head, a man named Charles McCarthy, claimed the books were "obscene" and "un-Christian." They didn't just ban them; they destroyed them. It's the kind of overkill that usually signals a deep-seated fear of new ideas. Bruce Severy, the teacher who assigned the book, ended up losing his job over the whole mess.

Vonnegut’s response, the I am very real Kurt Vonnegut letter, wasn't just about defending his book. He was defending his character. He told the board members that they had insulted him in a way that was nearly impossible to forgive. He pointed out that he had fought for his country—he was a Scout, he was a member of the 106th Infantry Division during World War II, and he had earned a Purple Heart. He wasn't some abstract monster. He was a person who had seen the worst of humanity firsthand and was trying to write about it with a shred of honesty.

Honestly, the letter is a masterclass in controlled rage. He tells them, "If you were to bother to read my books, to behave as educated persons would, you would learn that they are not sexy, and do not argue in favor of wildness of any kind. They beg that people be kinder and more responsible than they often are." It’s a gut punch. He basically calls them uneducated without ever using the word.

Why the phrase I am very real Kurt Vonnegut matters so much today

We live in an era where "book banning" has made a massive comeback. Whether it's coming from the left or the right, everyone seems to have a list of things they don't want kids to read. But the I am very real Kurt Vonnegut sentiment hits differently because it addresses the dehumanization of the creator. When people call for a book to be burned or banned, they aren't thinking about the person who spent years bleeding onto the page. They’re fighting a ghost. They’re fighting a symbol.

📖 Related: Why Grand Funk’s Bad Time is Secretly the Best Pop Song of the 1970s

Vonnegut’s letter forces you to look at the man behind the prose. He reminds the board that he is a "large, strong person" who earns a living by being "careful and responsible" with words. He wasn't some fly-by-night provocateur. He was a craftsman. By asserting his reality, he was telling the board that their actions had actual, physical victims. They weren't just burning paper; they were attacking his soul.

The irony of the burning

There is something deeply ironic about burning Slaughterhouse-Five. The book is, at its core, a meditation on the senselessness of destruction. It’s about the firebombing of Dresden. It’s about Billy Pilgrim being "unstuck in time" because he can't process the trauma of mass death. To take a book that mourns the incineration of a city and then toss it into a furnace is the kind of dark comedy Vonnegut would have written himself if he weren't so busy being horrified by it.

The content of the letter: A breakdown of his argument

Vonnegut didn't just ramble. He structured his defense around several key points that still serve as the best arguments against censorship today.

- The insult to citizenship: He reminded the board that he was an American citizen who had served his country. He viewed their actions as an attack on the very freedoms he fought for.

- The defense of morality: He challenged the idea that his books were "un-Christian" or "immoral." He argued that his work actually promoted kindness and responsibility.

- The failure of education: He suggested that the board members were failing their own children by shielding them from the world. If you don't teach kids how to handle complex ideas, you aren't protecting them; you're handicapping them.

- The personal toll: This is where the I am very real Kurt Vonnegut line comes in. He makes it clear that their insults "crawl" on his skin.

He wrote: "I am a real person, and you should learn that it is a very much more exposed and sensitive thing to be even a fairly good writer than you can imagine. My work, which should be a source of pride to my children, has been treated as though it were the work of a child-molester."

It’s heavy stuff. He doesn't hold back. He wants them to feel the weight of what they did.

👉 See also: Why La Mera Mera Radio is Actually Dominating Local Airwaves Right Now

Censorship in the 21st century

If you look at the American Library Association's reports lately, book challenges are at an all-time high. It’s not just North Dakota anymore; it’s everywhere. We’re seeing a resurgence of the same logic that drove the Drake school board in 1973. People are scared of "the other." They’re scared of ideas that challenge their worldview.

But the I am very real Kurt Vonnegut letter provides a blueprint for how to push back. It’s not about being louder or meaner than the censors. It’s about being more human. It’s about showing that stories are written by people, and when you silence a story, you are silencing a human voice. Vonnegut’s letter is still taught in schools today—ironically, in many of the same districts that once tried to ban his books—because it is a perfect example of how to stand up for your dignity.

Common misconceptions about the Drake incident

Some people think Vonnegut sued the school board. He didn't. He didn't need to. The letter itself was a more powerful weapon than any lawsuit could have been. It circulated through the press, it was published in newspapers, and it eventually became a staple of civil liberties literature.

Another misconception is that the school board eventually apologized. They didn't. In fact, they doubled down for a long time. It took years for the community to move past the stigma of the book burning. But Vonnegut won in the end. Slaughterhouse-Five is a classic. It’s read by millions of people every year. The names of the school board members who burned the books? They’re mostly forgotten, except as footnotes in Kurt Vonnegut's biography.

How to use Vonnegut's logic in modern debates

When you're dealing with someone who wants to ban a book or silence a creator, the natural instinct is to get defensive or angry. Vonnegut was angry, sure, but he was also incredibly precise.

✨ Don't miss: Why Love Island Season 7 Episode 23 Still Feels Like a Fever Dream

- Humanize the creator. Remind people that writers aren't faceless entities. They are members of the community.

- Highlight the hypocrisy. Vonnegut pointed out that the board members likely hadn't even read the books they were burning. This is almost always true in censorship cases.

- Defend the intent. Most "controversial" books aren't trying to corrupt youth; they're trying to explore the human condition.

- Stand your ground on dignity. Don't let people insult your character without calling it out.

The phrase I am very real Kurt Vonnegut isn't just a signature; it’s a declaration of existence. It says: You cannot erase me.

Practical next steps for readers and educators

If you care about the legacy of writers like Vonnegut, or if you're worried about the current state of censorship, there are a few things you can actually do. Don't just post a quote on Instagram.

- Read the banned books. Honestly, the best way to spite a censor is to read exactly what they don't want you to read. Go buy a copy of Slaughterhouse-Five or Breakfast of Champions.

- Support your local library. Librarians are the front-line soldiers in the war against censorship. They are the ones who have to deal with the angry phone calls and the board meetings. Go tell them you appreciate them.

- Show up to school board meetings. Most of the time, the people calling for bans are a very small, very loud minority. If a dozen people show up to support diverse reading materials, it changes the entire dynamic of the meeting.

- Write your own "I am very real" letter. If you see someone being unfairly targeted or silenced in your community, speak up. You don't have to be Kurt Vonnegut to tell the truth.

Vonnegut ended his letter by saying he didn't expect a response. He didn't get one. But he didn't need one. He had already said everything that needed to be said. He was real, his books were real, and the harm the board caused was real. By putting that on paper, he made sure that the fire in that North Dakota furnace wouldn't be the final word.

The reality is that censorship is usually a sign of weakness, not strength. It's an admission that your own ideas aren't strong enough to compete in the open market of thought. Vonnegut knew that. He knew that as long as he remained "very real," his words would outlast the flames. And they have. If you want to honor that, start by refusing to be silenced. Read the books. Support the teachers. Be kind, and for heaven's sake, be responsible. That's all Vonnegut ever really asked for.