You’ve seen the pose. A person looking up drawing tutorials or staring blankly at a high-ceilinged museum gallery, trying to figure out why their own sketches don’t look like the masters. It’s a specific kind of frustration. Honestly, the gap between what your eyes see and what your hand does is basically a canyon. Most people think they can’t draw because they lack "talent," but that’s usually a load of nonsense. Drawing isn't a gift from the gods; it’s a physical coordination skill, like driving a stick shift or playing tennis.

Why does it feel so hard?

The brain is a lazy organ. It likes shortcuts. When you look at a face, your brain says, "That's an eye," and it hands you a symbol—a football shape with a circle in the middle. But if you actually look at an eye? It’s a wet, fleshy sphere tucked into a socket, surrounded by skin folds that change every time the light shifts. A person looking up drawing basics has to learn how to kill the "symbol" part of their brain. You have to stop drawing what you think things look like and start drawing what is actually there.

👉 See also: Why Your Camping Pot Stainless Steel Choice Actually Matters for Your Next Trip

Why Looking Up is the First Step to Getting Better

When we talk about a person looking up drawing references or inspiration, we’re talking about the observational phase. Most beginners skip this. They sit down, grab a HB pencil, and expect the image to just flow out of their fingers. It doesn't work that way. Even professional concept artists at places like Riot Games or Disney spend hours just looking.

Observation is 90% of the work.

I remember reading about Betty Edwards, the author of Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain. She’s a legend in the art education world. Her whole philosophy is built on the idea that drawing is a global skill—a set of components that you integrate. She famously used the "upside-down drawing" exercise. By turning a reference image upside down, you force the brain to stop recognizing "a man" or "a chair" and start seeing lines, edges, and spaces. It’s a bit of a brain hack. It bypasses the naming centers of the brain.

The Anatomy of Observation

If you’re a person looking up drawing advice, you've probably heard of "negative space." It sounds like some pseudo-intellectual art term, but it’s actually the most practical tool you have. Negative space is the area around the object. If you’re drawing a chair, don’t draw the chair. Draw the shapes of the air trapped between the rungs.

It’s weirdly easier.

Our brains are less opinionated about what "empty air" looks like, so we don't try to simplify it into a symbol. You end up with a more accurate chair by not drawing the chair at all. It’s a paradox that every art student eventually hits, usually during a long, boring figure drawing session where the model has been standing still for forty minutes and the smell of charcoal is starting to get to everyone.

Tools Matter (But Not the Way You Think)

Don't go out and buy a $200 set of Copic markers or a top-of-the-line Wacom tablet yet. Seriously. A person looking up drawing gear often falls into the "gear acquisition syndrome" trap. You think the tools will make the art. They won’t.

- Pencils: A simple 2B and 4B are all you need to start.

- Paper: Use cheap newsprint for drills. If you use expensive paper, you’ll be too scared to mess up.

- Erasers: Get a kneaded eraser. You can shape it into a point to lift highlights.

- References: Use real life whenever possible. Photos flatten 3D space.

The Mental Block Nobody Mentions

There is a psychological wall that every person looking up drawing hits around the three-week mark. The "Ugly Phase." This is when your observational skills (your ability to see mistakes) are developing faster than your motor skills (your ability to fix them).

👉 See also: Why Bodega Cats in New York are More Than Just a Meme

You start to hate your work.

This is actually a good sign. It means your eye is getting sharper. You’re seeing the world more clearly than you were a month ago. The trick is to keep pushing through until your hands catch up. Kim Jung Gi, the late, great master of perspective who could draw entire cities from memory, used to talk about "observational memory." He spent decades just watching people, cars, and animals. He wasn't just looking; he was recording.

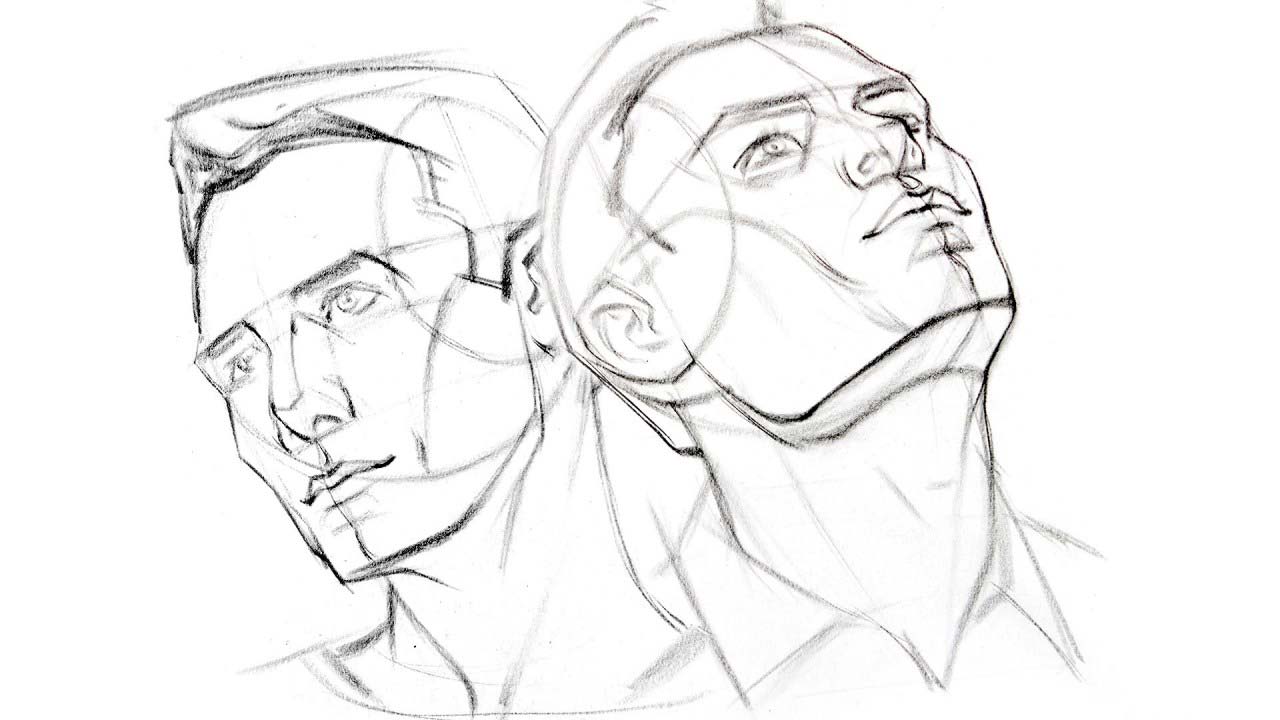

Perspective and the Person Looking Up Drawing

Perspective is usually where people quit. It’s math, basically. One-point, two-point, three-point perspective—it’s the architecture of the visual world. If you’re looking up at a tall building, that’s three-point perspective. The lines don't just go back to the horizon; they also vanish toward a point in the sky.

If you get the perspective wrong, the drawing feels "off" even if the shading is perfect. You can’t hide bad structure with pretty colors. Think of it like a house. Perspective is the foundation and the framing. Shading is the paint and the furniture. If the foundation is cracked, the nicest sofa in the world won’t save the building from leaning.

The Rise of Digital Learning

Today, a person looking up drawing has resources that would have made Renaissance masters weep with envy. You have Procreate, Photoshop, and infinite YouTube tutorials from artists like Stan Prokopenko (Proko) or Aaron Blaise.

Proko is specifically great for anatomy. He breaks down the human body into "mannequinization"—turning complex muscles into simple boxes and cylinders. It makes the human form less intimidating. Instead of trying to draw a complex deltoid, you’re just drawing a shield shape that wraps around a cylinder.

But there’s a downside to the digital age.

The "Undo" button (Cmd+Z) is a dangerous drug. It stops you from committing to your lines. In traditional drawing, if you make a mark with a pen, it's there. You have to work with it. That pressure forces you to be more intentional. If you’re a person looking up drawing tips, try doing a week of "ink only" sketches. No pencils, no erasers. You’ll be surprised at how quickly your confidence grows when you can't take back your mistakes.

Light, Shadow, and the Illusion of Depth

Everything we see is just light bouncing off surfaces. That’s it. To create the illusion of 3D on a 2D piece of paper, you need to understand the "Value Scale."

Value is just how light or dark something is.

If you squint your eyes at a person looking up drawing in a park, their colorful clothes disappear and you just see blocks of light and dark. This is called "simplifying values." Most beginners don't go dark enough. They’re afraid of the black charcoal. But without deep shadows, you don't get bright highlights. You need contrast.

A common mistake is "pillowing"—shading everything softly toward the edges. Real shadows have edges. Some are soft (form shadows), and some are sharp (cast shadows). Knowing the difference is what separates a flat drawing from one that looks like it’s about to pop off the page.

Actionable Steps for the Aspiring Artist

If you are that person looking up drawing techniques right now, here is what you actually need to do. Not tomorrow. Today.

First, grab a boring object. A coffee mug or a crumpled paper bag is perfect. Set it under a single strong light source—a desk lamp works great.

💡 You might also like: Green Nails for Christmas: Why This One Shade is Replacing Red in 2026

Next, set a timer for ten minutes. Spend the first five minutes just looking. Don't touch the pencil. Trace the edges of the object with your eyes. Notice where the shadow is darkest. Look for the "core shadow" and the "reflected light" on the bottom edge.

When you finally start drawing, don't draw the object. Draw the shapes of the shadows. If you get the shadow shapes right, the object will magically appear.

Finally, do this every day. Even for five minutes. Drawing is a muscle. If you don't use it, it atrophies. If you use it daily, you’ll start seeing the world differently. You’ll be standing in line at the grocery store and you’ll find yourself looking at the way the fluorescent light hits a cereal box, and you’ll think, "I know how to draw that."

That’s when you know you’ve moved past being a person looking up drawing and started being an artist.

The most important thing is to lower your expectations. Your first 100 drawings are going to be terrible. Get them out of your system as fast as possible. Once you stop caring if the drawing is "good," you free yourself up to actually learn. The goal isn't a pretty picture; the goal is a better understanding of the visual world.

Keep your head up, keep looking at your references, and keep making marks. The progress is slow, then it’s sudden. You’ll struggle with a hand for a month, and then one day, it just clicks. You’ll draw a thumb that actually looks like a thumb, and it’ll be the best feeling in the world.

Stop researching and start sketching. The paper is waiting.