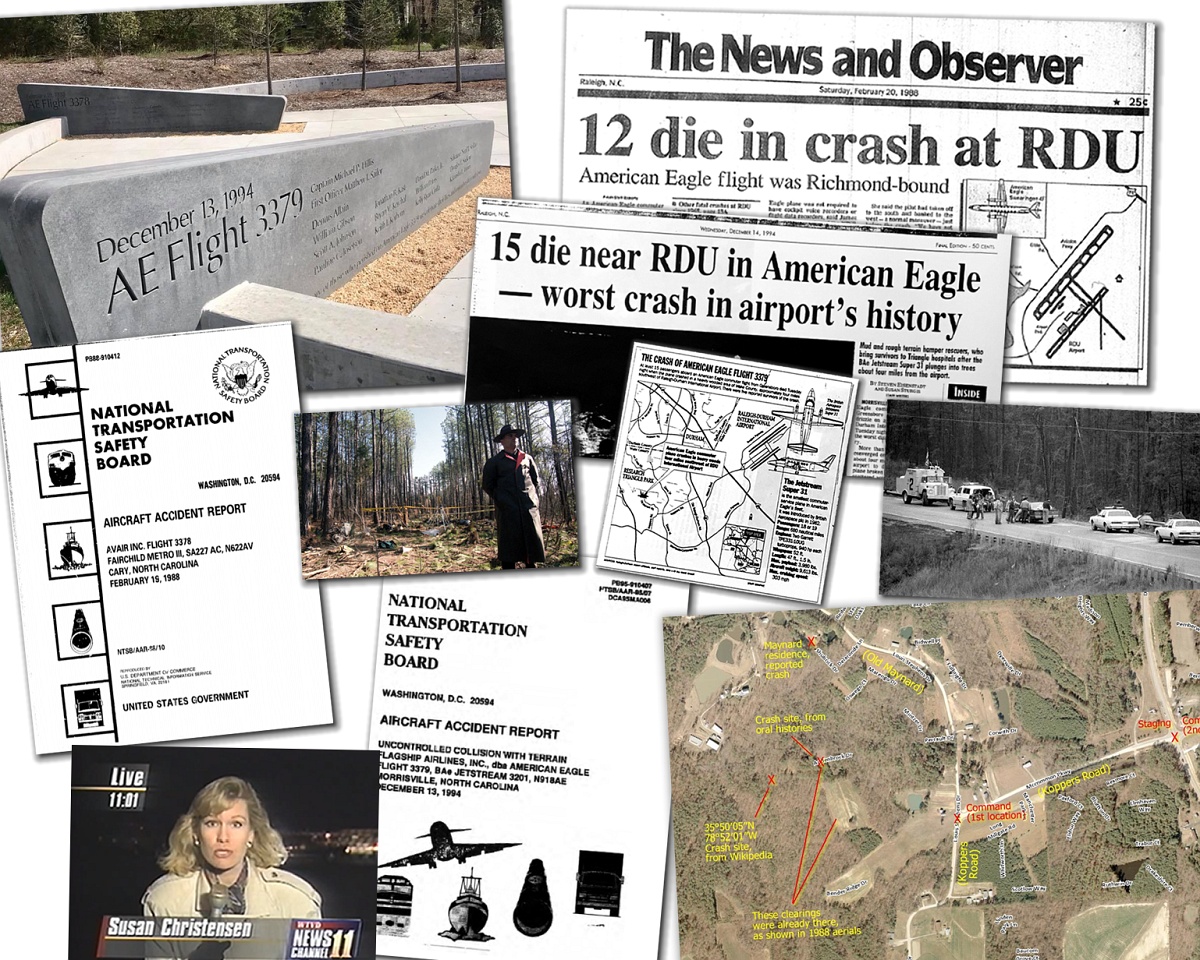

It was a cold Tuesday in December 1994. The sky over North Carolina was a mess—low clouds, freezing drizzle, the kind of weather that makes even seasoned frequent fliers a bit twitchy. American Eagle Flight 3379, a Jetstream 32 turboprop operated by Flagship Airlines, was on its way from Greensboro to Raleigh-Durham. It should’ve been a routine hop. It wasn't. Just four miles from the runway, the plane dropped out of the sky and slammed into a wooded area near Morrisville. 15 people died. Five survived, though "survived" feels like a light word for the trauma they walked away with.

Most people look at a plane crash and want a simple answer. Was it the engine? Was it the ice? With American Eagle Flight 3379, the answer is more about the human brain than the hardware. This wasn't just a "mechanical failure" story. It was a breakdown in how a pilot interprets what a machine is telling him. Honestly, when you look at the NTSB records, it’s a chilling reminder of how fast things go sideways when a pilot loses his "situational awareness."

A Simple Light and a Fatal Mistake

So, what actually happened in the cockpit? The trouble started during the approach to RDU. A "moments-of-terror" situation began with something tiny: an ignition light. Specifically, the left engine’s "ignition" light flickered on. In the Jetstream 32, this often meant the engine had experienced a momentary flameout and the auto-igniters were trying to kick it back to life. Captain Michael Hillis, who was 29 at the time, thought the engine had actually failed. It hadn't. It was just a momentary hiccup, likely caused by the way he manipulated the power levers.

He panicked. Well, maybe "panic" is too strong a word—he misdiagnosed. He assumed he was flying on one engine. This is where it gets technical but also very human. When you think you’ve lost an engine in a twin-prop plane, you have to follow a very specific set of steps to keep the plane balanced. Hillis didn't. He allowed the plane’s speed to bleed off while trying to troubleshoot a problem that wasn't really there. Because he thought the left engine was dead, he didn't use it. But the engine was actually fine; it was just sitting at idle.

The speed kept dropping. 120 knots. 110 knots. 103 knots.

The Aerodynamics of a Nightmare

You’ve got to understand how these smaller commuter planes work. They don't have the massive thrust-to-weight ratios of a Boeing 777. In a Jetstream 32, if you let your airspeed get too low during an approach—especially if you're messing with the power settings unevenly—you risk a stall.

📖 Related: Weather Forecast Lockport NY: Why Today’s Snow Isn’t Just Hype

As the plane slowed down, it reached its "minimum controllable airspeed." The aircraft started to roll. It wasn't a gentle tilt. It was a violent, asymmetric stall. Because the pilots were focused on the imaginary engine failure, they missed the biggest warning sign of all: the plane was literally stopping in mid-air. The NTSB later pointed out that if they had just pushed the nose down and shoved both throttles forward, they probably would’ve flown right out of it. Instead, they stayed confused until the trees were right in front of the windshield.

The Problem With Captain Hillis’s Record

Here is the part of the American Eagle Flight 3379 story that most people find the most frustrating. It turns out, Michael Hillis probably shouldn't have been in that seat. After the crash, investigators started digging into his training records at Comair, his previous employer. What they found was a red flag the size of a house.

He had struggled. A lot.

Specifically, he had a history of failing checkrides and showing "poor judgment" in emergency simulations. Comair had basically encouraged him to resign because his performance wasn't up to par. Yet, he was hired by Flagship Airlines (operating as American Eagle) shortly after. This raised a massive firestorm in the aviation industry about "pilot filtering." How does a pilot with a documented history of struggling under pressure end up captaining a commercial flight?

The industry call it "the rubber stamp." Sometimes, airlines were so desperate for pilots during the regional expansion of the 90s that they didn't look closely enough at the "soft" failures in a pilot's past.

👉 See also: Economics Related News Articles: What the 2026 Headlines Actually Mean for Your Wallet

The Survivors and the Aftermath

It’s easy to talk about stall speeds and NTSB reports, but the ground reality in Morrisville was horrific. The plane broke apart on impact. The tail section stayed relatively intact, which is where the five survivors were located. One survivor, a man named Richard DeMary, became a bit of a hero that night. Despite being injured, he pulled other passengers out of the wreckage. He even tried to reach the cockpit, but the fire was too intense.

Imagine the woods in North Carolina in December. Dark. Wet. Smelling of jet fuel. The emergency responders had a hard time even finding the site because it was so tucked away in the forest.

The NTSB's final report was scathing. They didn't just blame the pilot; they blamed the system. They cited the airline's failure to properly vet Hillis and the lack of oversight in how regional pilots were trained for "engine-out" scenarios. They basically said the crash was "avoidable in every sense of the word."

Why This Crash Changed How You Fly Today

We don't just study crashes to be morbid. We study them to fix things. American Eagle Flight 3379 led to some massive shifts in the industry.

First, it changed the Pilot Records Improvement Act (PRIA). Before this crash, it was surprisingly hard for one airline to see the full training history of a pilot from another airline. There were privacy concerns and legal hurdles. After 1994, the rules tightened up. Now, if you fail a checkride at a small regional carrier, that black mark follows you to the majors. No more hiding "poor judgment" records.

✨ Don't miss: Why a Man Hits Girl for Bullying Incidents Go Viral and What They Reveal About Our Breaking Point

Second, it changed how we train for "Asymmetric Thrust." Pilots are now trained much more rigorously to identify that a "flickering light" does not equal a "dead engine." They practice staying on the flight instruments rather than reacting with their gut.

Key Takeaways from the Flight 3379 Investigation:

- Trust the Airspeed: No matter what is wrong with the engine, the plane won't fly without speed. The pilots forgot the basics of "Aviate, Navigate, Communicate."

- Vetting Matters: A pilot’s past performance is the best indicator of their future behavior in a crisis.

- The "Company Culture" Factor: Flagship Airlines faced intense pressure to keep schedules, which some argued led to a "check-the-box" mentality in training.

What You Should Know Now

If you’re looking into the history of American Eagle Flight 3379, don't just look at the wreckage photos. Look at the NTSB's "Probable Cause" statement. It’s a masterclass in understanding human error. The crash wasn't caused by a mechanical failure; it was caused by the perception of one.

To stay informed on aviation safety, you can actually browse the NTSB’s public database for "AAR-95/07." That’s the official report number. It’s dense, dry, and absolutely haunting. It lists every second of the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) transcript. Hearing—or reading—the confusion in those final moments is a powerful lesson in why "slow is smooth, and smooth is fast" in any high-stakes environment.

Next time you’re on a small regional jet and you feel a little bump or see a light flicker, remember that the pilots up front are now trained specifically on the lessons learned from Flight 3379. The systems are better, the records are more transparent, and the training is lightyears ahead of where it was in 1994.

To dig deeper into this specific era of aviation, you should look into the "Advanced Qualification Program" (AQP) that many airlines adopted shortly after. It shifted training from "can you do this maneuver" to "can you manage this scenario." It’s a subtle difference that has saved countless lives in the thirty years since that plane went down in Morrisville.