The ground feels solid. Until it isn't. If you live in the American Midwest, specifically near the "Bootheel" of Missouri, you’ve likely seen a Madrid fault line map at some point in a school textbook or a local news segment. It’s a jagged, terrifying set of lines that looks like a lightning strike across the map of the United States. But here’s the thing: most of those maps are actually kind of misleading. They imply we know exactly where the cracks are. We don't.

Deep beneath the Mississippi River Valley lies the New Madrid Seismic Zone (NMSZ). It isn't a single, clean line like the San Andreas in California. It’s a messy, ancient "failed rift" buried under miles of river sediment. This makes mapping it a nightmare for the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). You can't just walk outside and see a fault scarp in Memphis or St. Louis. It's hidden. It's silent. And according to history, it’s incredibly dangerous.

What the Madrid Fault Line Map Actually Shows You

If you look at a modern Madrid fault line map, you’ll see three main segments. There’s the Cottonwood Grove fault, the Reelfoot fault, and the Ridgely fault. They form a sort of "Z" shape. This zigzag pattern is the result of the Earth’s crust trying to pull apart hundreds of millions of years ago. It failed to split North America in half back then, but it left a permanent weakness in the plate.

Geologists like Seth Stein from Northwestern University have spent years debating how much stress is actually building up there. Some think the zone is "shutting down." Others, like the folks at the USGS, point to the 1811-1812 quakes as proof that the Midwest is a ticking clock. Back then, the shaking was so violent it reportedly rang church bells in Boston. It made the Mississippi River run backward. Imagine that happening today with a population of millions sitting right on top of it.

💡 You might also like: Tahlequah and the Killer Whale Dead Calf: Why We Can't Look Away

The map isn't just about lines, though. It’s about soil. This is where it gets sketchy. The Midwest is covered in "alluvium"—thick, wet river mud. When a big quake hits, this mud undergoes liquefaction. Basically, the ground turns into a milkshake. A Madrid fault line map that only shows the faults is missing the bigger picture: the "hazard zones" that extend hundreds of miles away because the soft soil carries seismic waves much further than the hard rock in California does.

Why Memphis and St. Louis are sweating

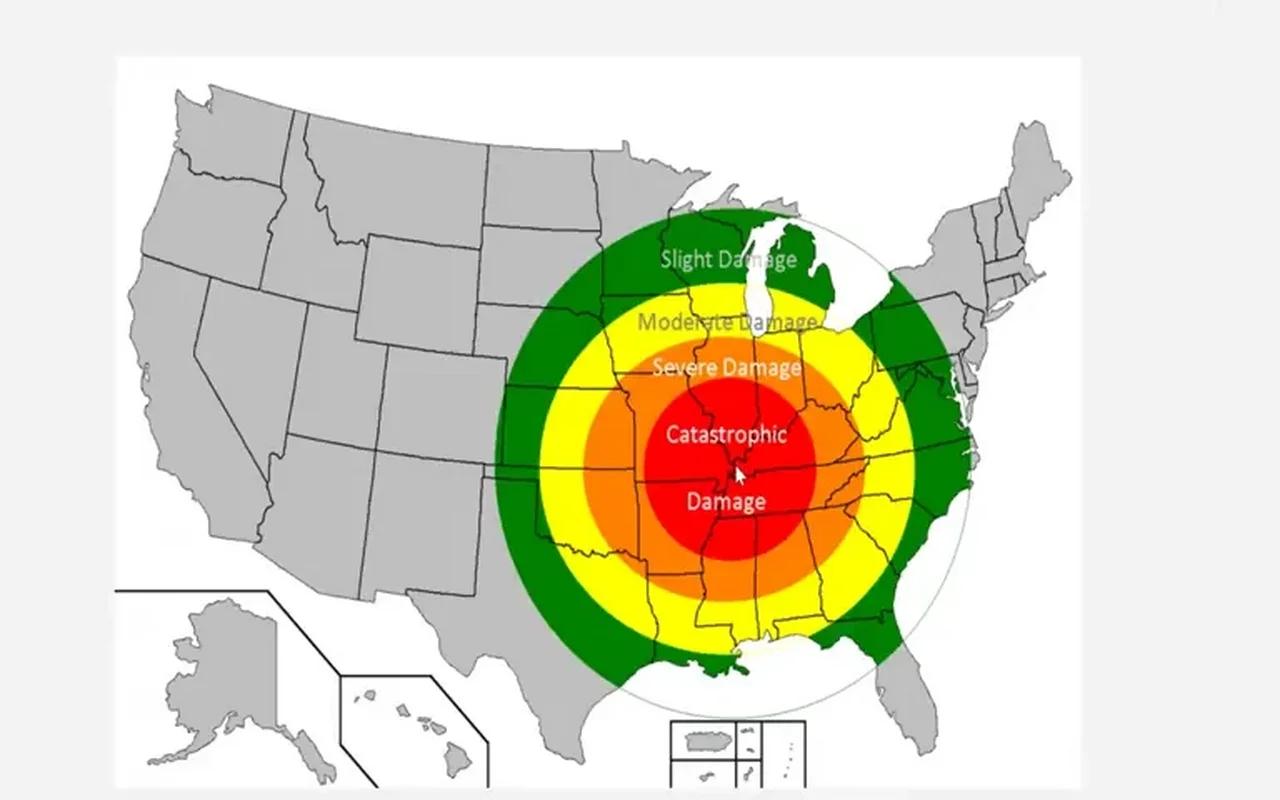

It's not just about being "on the line." It's about how far the energy travels. In 1811, the tremors were felt over an area of 5 million square kilometers. For comparison, the 1906 San Francisco quake was felt over about 160,000 square kilometers. That’s a massive difference.

If you're looking at a Madrid fault line map today, you'll see high-risk areas stretching into Illinois, Kentucky, Arkansas, and Tennessee. Memphis is particularly vulnerable. A lot of the older brick buildings there aren't reinforced. They weren't built with the New Madrid in mind. Honestly, if a 7.7 magnitude hits tomorrow, the infrastructure damage would be astronomical. We're talking about cracked pipelines, collapsed bridges over the Mississippi, and power grids going dark for weeks.

The Problem With Predicting the "Big One"

People want dates. They want to know if they should buy earthquake insurance before their policy renews next month. But the science is, frankly, frustrated.

GPS monitoring has shown very little movement in the New Madrid region over the last few decades. This led some researchers to suggest that the fault is "dead." But then you have the paleoseismologists. These are the experts who dig trenches and look at sand blows—remnants of ancient liquefaction. They've found evidence that massive quakes happen here roughly every 400 to 500 years. If the last one was in 1812, we’re still in the "quiet" window, but the window is getting smaller.

- The 1811-1812 Sequence: Not one quake, but three massive ones over three months.

- The Magnitude Debate: Were they 8.0? Or more like 7.2? Most modern estimates lean toward the low 7s, but in the Midwest, a 7.0 feels like a 9.0 because of the geology.

- Modern Microseismicity: The zone still pops. There are hundreds of tiny quakes every year that you can't feel, but the sensors catch them. They trace the Madrid fault line map perfectly, showing that the "Z" is still active.

The Real Danger is the "Sand Blow"

In 2026, we have better tech than ever to track this. We use LIDAR to see through the trees and see the ripples in the earth. What we see are thousands of "sand blows"—spots where pressurized water and sand shot out of the ground like geysers during the 1812 quakes. Some of these are the size of football fields. They are everywhere in the Bootheel. If you see a map covered in little dots across Southeast Missouri, those are the scars of a violent past.

Is the Hazard Overstated?

There is a legitimate "civil war" in the geological community about the Madrid fault line map. On one side, you have the "Alarmists" (mostly federal agencies and emergency managers). They say we must prepare for the worst-case scenario because the stakes are too high to ignore. On the other side, you have the "Skeptics" who argue that the North American plate is stable and the 1812 quakes were a fluke or a dying gasp of an old system.

Who is right? We probably won't know until it happens. But building codes have already changed. If you build a hospital in Memphis today, it has to meet much higher seismic standards than one built in 1970. This adds millions to construction costs. That's why the accuracy of the Madrid fault line map matters—it’s not just science; it’s billion-dollar economics.

How to Read Your Local Risk

Most people look at a seismic hazard map and see red. Red is bad. But you need to look at the "Peak Ground Acceleration" (PGA). This tells you how hard the ground will actually shake. In the New Madrid zone, the PGA can be incredibly high even far from the fault.

- Check your soil type. Are you on bedrock or river silt? Silt equals trouble.

- Look at the "Z" segments. If you live within 50 miles of the Reelfoot fault, you're in the bullseye.

- Don't ignore the Wabash Valley. North of the New Madrid, there’s another fault system in Indiana and Illinois. It’s like the New Madrid’s quieter, but still dangerous, cousin.

Insurance companies use these maps to set your rates. If your house is sitting on an area marked as "High Liquefaction Potential," you’re going to pay more. It’s that simple.

Moving Forward: Actionable Steps for the "Hidden" Fault

You can't move the fault. You can't stop the plates from shifting. But you can stop being a victim of a map you don't understand.

First, get your hands on a high-resolution Madrid fault line map from the USGS or your state’s geological survey. Don't just look at the lines; look at the "liquefaction susceptibility" layers. If you are in a high-risk zone, the very first thing you should do is check your water heater. If it’s not strapped to the wall studs, a tiny tremor will knock it over, break the gas line, and burn your house down before the shaking even stops. Most "earthquake deaths" in the US aren't from the ground swallowing people; they're from fires and falling masonry.

Second, rethink your "safe spot." In the Midwest, many people are trained for tornadoes—go to the basement. In an earthquake, the basement can be a death trap if the house shifts off its foundation. You need to "Drop, Cover, and Hold On" under a sturdy piece of furniture.

Finally, recognize that the Madrid fault line map is a living document. It changes as we get better satellite data and deeper drill samples. It’s a reminder that the "solid" ground beneath the cornfields is actually a complex, shifting puzzle. We’re just living on the top layer.

Stay informed by checking the USGS Earthquake Hazards Program periodically. They update their National Seismic Hazard Model (NSHM) every few years, and these updates directly influence everything from your insurance premiums to the strength of the bridge you drive over every morning. Respect the rift, but don't live in fear of it—just build smarter.