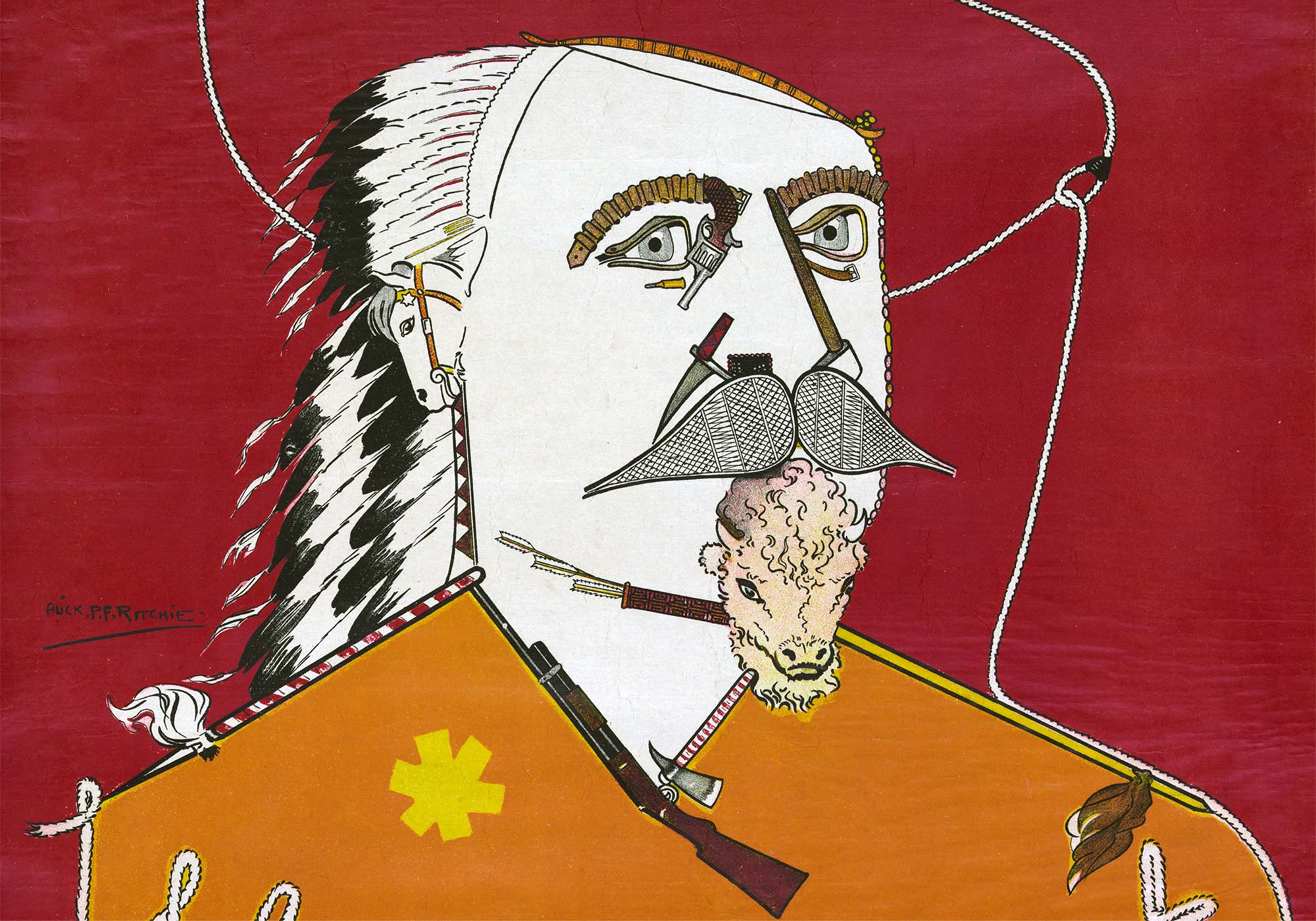

William Frederick Cody wasn't just a man; he was a brand before "branding" was a word people used at dinner parties. You probably know him as Buffalo Bill. Maybe you picture the fringed buckskin jacket, the flowing white hair, or that goatee that looked like it belonged on a Victorian gentleman who’d spent too much time in the sun. But honestly? Most of the "history" we consume about him is actually just leftovers from his own marketing department. He was the world's first true global superstar, a man who played himself on stage so convincingly that the world forgot where the scout ended and the showman began.

From Pony Express to the Great Plains

Cody’s life started in 1846 in Iowa, and it didn't take long for things to get messy. His father died after being stabbed for speaking out against slavery—a brutal introduction to the political volatility of the era. By the time he was eleven, Cody was working. He wasn't playing with wooden blocks; he was riding as a "boy extra" on wagon trains.

📖 Related: Race Swap Sloppy Seconds Twitter: Why This Phrase Is Taking Over Your Feed

Did he actually ride for the Pony Express? That’s where things get murky. Cody claimed he made the longest non-stop ride in the Express's history at age 14. Modern historians like Louis S. Warren, who wrote Buffalo Bill's America, suggest this might be a bit of "creative resume building." Whether he rode every mile he claimed doesn't change the fact that he was out there in the dirt and the danger while most kids his age were learning long division. He was a scout for the Union during the Civil War. He was a hunter. He was the real deal, even if he eventually fluffed the pillows of his own legend.

How He Actually Got the Name

You might think he got the nickname "Buffalo Bill" because he was some kind of conservationist. He wasn't. Not then, anyway. He got it because he was a professional meat provider. After the Civil War, the Kansas Pacific Railroad needed to feed its workers. Cody took a contract to provide buffalo meat.

He killed 4,280 head of buffalo in seventeen months.

It wasn't just a job; it was a competition. He famously won a "buffalo-killing contest" against a man named William Comstock to see who deserved the title. Cody won 69 to 46. It’s a grim statistic by today’s standards, but in the 1860s, it made him a folk hero. This is the part of the story that often gets sanitized. We like the showman, but we forget the sheer scale of the ecological shift he was a part of. He was a man of his time, and that time was incredibly bloody.

The Wild West Show: Reality as Entertainment

In 1883, Cody did something radical. He took the "West"—the violence, the horses, the dust—and he turned it into a circus. But he hated calling it a show. He called it "Buffalo Bill's Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World."

It wasn't a play. It was an exhibition.

📖 Related: Sherri Shepherd of The View: What Most People Get Wrong

He hired real people. When you saw Sitting Bull in the arena, that wasn't an actor in a wig. That was Sitting Bull. When you saw Annie Oakley shooting clay pigeons, she was actually hitting them. This blurred the lines between history and entertainment so effectively that for many Europeans and Easterners, Buffalo Bill’s show was the reality of the American frontier.

The logistics were insane. We’re talking about a traveling city. Hundreds of horses, dozens of buffalo, and a cast of hundreds moved by train across the United States and Europe. In 1887, he performed for Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee. Think about that: a guy who started out as a literal "boy extra" on a wagon train was now being toasted by the Queen of England. He brought the American myth to the world, and the world bought it wholesale.

The Paradox of his Relationships

Cody is a bundle of contradictions. He made his name fighting Native Americans as a scout, yet he was one of the few voices of his era calling for their fair treatment. He famously said, "Every Indian outbreak that I have ever known has resulted from broken promises and broken treaties by the government."

He paid his Native American performers the same wages as his white performers. He gave them the right to bring their families on tour. This doesn't erase the fact that he was essentially commodifying their culture for profit, but it adds a layer of complexity that doesn't fit into a "hero or villain" box.

The same goes for his views on women. He was a staunch supporter of women's suffrage. He believed women should work and be paid exactly what men were paid. "If a woman can do the same work that a man can do and do it just as well, she should have the same pay," he told reporters. This wasn't a popular opinion in the 1890s. He was a progressive in a buckskin jacket.

The Tragic End of the Legend

Money was always Cody's ghost. He made millions. He lost millions. He invested in mines that didn't produce and irrigation projects that took too long to pay off. By the end of his life, he didn't even own his own name. The "Buffalo Bill" trademark was tied up in debts.

He died in 1917, and even his burial was a point of contention. He wanted to be buried on Cedar Mountain in Wyoming, near the town he founded (Cody, Wyoming). Instead, he was buried on Lookout Mountain in Colorado. Rumors have persisted for over a century that his body was secretly swapped and moved to Wyoming under the cover of night. It’s probably not true, but it’s the kind of story Cody would have loved. He knew that a good story is often more durable than the truth.

Why Buffalo Bill Still Matters in 2026

We live in an age of influencers and curated personas. Cody was the original. He taught us how to package "authenticity" and sell it back to the public. He created the Western genre—the tropes of the cowboy, the "noble savage," and the rugged individualist all stem from his arena shows.

If you want to understand the real Buffalo Bill, you have to look past the fringe. You have to see the man who was genuinely grieving for his lost son, the man who struggled with a failing marriage, and the man who was terrified of being forgotten. He wasn't just a character. He was a pioneer who got caught in his own spotlight.

Actionable Ways to Explore the Real History

If you’re tired of the cardboard cutout version of Cody, there are real places where the history feels a bit more tangible.

- Visit the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming. This isn't just a roadside attraction. It’s an affiliate of the Smithsonian and holds the most extensive collection of Cody’s personal items, letters, and firearms. It gives you the "why" behind the "what."

- Read "The Colonel’s Dream" or original newspapers from the 1880s via the Library of Congress. Digital archives allow you to see how the media of his day treated him—half god, half curiosity.

- Research the "Cody Scout" documents. If you want to see the military side of his life without the glitter, look into the official military records of his scouting for the 5th Cavalry. It’s dry, but it’s the raw data of his early life.

- Examine the impact of the Wild West show on European perceptions. If you’re in Europe, many local historical societies in cities like London or Paris still have records of the show’s visit and the massive cultural shock it caused.

Buffalo Bill didn't just tell the story of the West; he built the stage it still sits on today. Understanding him requires acknowledging both the brilliance of his vision and the casualties of his ambition. He was a hunter who became a conservationist, a fighter who became an advocate, and a poor kid from Iowa who became the most famous man on Earth.

Next time you see a Western movie, remember that Cody likely influenced the costume design, the pacing, and the very idea that the West was something worth watching.