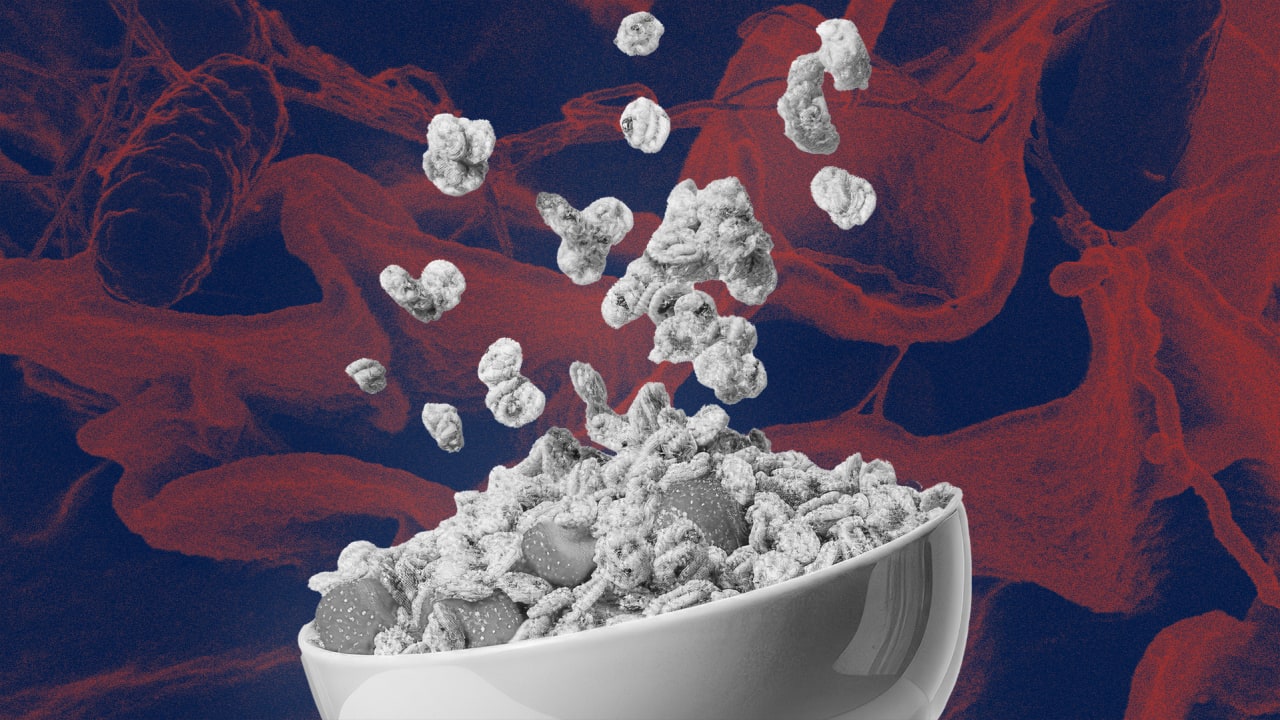

It started with a few granola bars. Then, honestly, it spiraled into a massive headache for millions of American households. If you’ve got a box of Chewy bars or a tub of oats sitting in the back of your pantry, you’re probably wondering if it’s actually dangerous or just a corporate legal team being overly cautious.

The recall on Quaker Oats wasn't just a minor blip. It was a massive safety action triggered by Salmonella concerns that eventually grew to include hundreds of different product varieties. We aren't just talking about one "bad batch." This was a systemic issue that forced the company to pull products from shelves across all 50 states, Puerto Rico, Guam, and Saipan.

Why the recall on Quaker Oats happened in the first place

Salmonella. That’s the short answer. Specifically, the Quaker Oats Company, which is owned by PepsiCo, found the potential presence of Salmonella during routine testing. It's a nasty bacterium. Most people think of it as something you only get from raw chicken or sketchy eggs, but it’s a huge problem in dry food processing plants too.

How does it get into a granola bar? Usually, it's environmental. If a facility has a leak, or if dust from a raw ingredient area migrates to a "ready-to-eat" line, the bacteria can settle and survive for a long time in dry environments. Once it gets into the machinery, every bar passing through that line is at risk.

The initial announcement hit in late 2023, but the scope exploded in early 2024. They kept adding more items. It felt like every time you checked the news, a new flavor of Cap’n Crunch cereal or a specific variety of protein bar was added to the "do not eat" list.

✨ Don't miss: Egg Supplement Facts: Why Powdered Yolks Are Actually Taking Over

The science of the risk

Salmonella isn't a joke. For a healthy adult, it usually means three days of wishing you were dead while stuck in the bathroom. Fever, nausea, and cramps are the standard package. But for kids, the elderly, or anyone with a weakened immune system, it can be fatal. This is why the FDA gets so aggressive. They don't wait for thousands of people to get sick. If the bacteria is found on a contact surface or in a sample, the whole lot goes in the trash.

Identifying the affected products in your kitchen

You can't just look at a box and see if it’s contaminated. It doesn't smell bad. It doesn't look fuzzy. The only way to know is by checking the "Best Before" dates and the UPC codes.

The list is honestly exhausting. It includes the classic Quaker Chewy Bars (Big Chewy, 25% Less Sugar, Variety Packs), Quaker Puffed Granola Cereal, and even those Quaker On-the-Go Snack Boxes. They even had to pull certain Gatorade Protein Bars because Quaker manufactures those too.

Check your "Best Before" dates. Most of the recalled items have dates ranging from early 2024 through October 2024. If you have a Costco-sized box of granola bars you bought last year and forgot about, go look at it right now. Seriously.

🔗 Read more: Is Tap Water Okay to Drink? The Messy Truth About Your Kitchen Faucet

What about the plain oats?

This is a common point of confusion. For a long time, the standard "Old Fashioned" oats in the cardboard cylinder weren't part of the main recall. People were panicking about their morning oatmeal, but the focus was mostly on the processed snack products—the stuff made in specific facilities where the contamination was identified. However, because the list grew so much, many consumers just stopped buying the brand entirely out of fear.

The ripple effect on the supply chain

When a giant like PepsiCo pulls millions of units, it creates a vacuum. Suddenly, store brand granola bars are sold out. Prices for competitors like Nature Valley or Kind might tick up because of the demand.

But for Quaker, the cost is astronomical. We aren't just talking about the lost sales. There's the cost of the logistics—shipping all that "trash" back or verifying its destruction—and the massive blow to brand trust. Quaker has been a staple of the American breakfast for over 140 years. When you're "the" oatmeal company and your oats aren't safe, that’s a hard PR pivot.

What you should do if you find a recalled box

Don't eat it. Don't give it to your dog. Just don't.

💡 You might also like: The Stanford Prison Experiment Unlocking the Truth: What Most People Get Wrong

- Take a photo of the UPC and the date code. You’ll want this for your refund.

- Throw it away. The company recommends putting it in a sealed bag so no animals get into it in the trash.

- Visit the official Quaker Recall website. They set up a specific portal where you can enter your information and get reimbursed. You don't usually need a grocery store receipt, which is a lifesaver since most of us don't keep those for months.

How to get your money back

Quaker actually made the refund process relatively painless compared to some other food recalls I've seen. You go to their site, click through the prompts, and they usually send out coupons or checks to cover the cost of the product. It takes a few weeks, but it's better than nothing.

Lessons learned from the Quaker situation

Food safety is a moving target. Even with the best technology, a single microscopic gap in a seal or a lapse in a cleaning protocol can shut down a multi-billion dollar production line.

This recall serves as a reminder to check your pantry periodically. We all have that "forgotten shelf." Food recalls often stay active for months after the initial news cycle dies down. Just because you haven't heard about the recall on Quaker Oats on the nightly news recently doesn't mean those bars in your cupboard are suddenly safe.

Actionable Steps for Consumers

- Check the Official List: Go to the FDA’s recall database or Quaker’s specific site to see the full list of UPC codes. It is much longer than you think.

- Sign up for alerts: The USDA and FDA have email lists. It sounds boring, but it’s the only way to know about these things before you've already eaten half the box.

- Sanitize your pantry: If you had an open box of recalled bars sitting on a shelf, wipe that shelf down. Cross-contamination is rare with dry goods, but why take the risk?

- Verify your "Safe" Oats: If you're buying new Quaker products, look for the "new" stock. Retailers were supposed to clear out all old inventory, but in smaller convenience stores, older boxes can sometimes linger. Check the dates. If it was made after the recall window, you're good to go.

The reality of modern food production is that we trade a bit of transparency for convenience. When that system breaks, as it did here, the responsibility falls on us to clear out the leftovers. Go check your pantry. It only takes two minutes.