You’ve probably heard the name whispered in late-night documentary voiceovers or seen it buried in a dense Twitter thread about "forever wars." Honestly, the Project for the New American Century (PNAC) sounds like something out of a Tom Clancy novel. It isn’t. It was very real, very influential, and it basically wrote the script for how the United States interacted with the world for the first decade of the 2000s.

If you want to understand why the Middle East looks the way it does today, you have to look at a small group of people in a Washington D.C. office in 1997. They had a vision. They had a plan. And for a while, they had the keys to the White House.

What was the Project for the New American Century anyway?

Think back to the late 90s. The Cold War was over. The Soviet Union had collapsed. People were actually talking about the "end of history." In this vacuum, a group of neo-conservatives felt the U.S. was drifting. They were worried. They thought America was becoming "soft."

So, William Kristol and Robert Kagan started PNAC. It wasn't some shadowy cabal in a basement; it was a non-profit educational organization. Their goal was simple: promote American global leadership. They believed that American leadership was good for America and good for the world. But their definition of "leadership" was heavy on military might.

The roster of people who signed their founding Statement of Principles reads like a "who’s who" of the Bush administration. Dick Cheney. Donald Rumsfeld. Paul Wolfowitz. Jeb Bush. These weren't outsiders. They were the future architects of the Iraq War. They argued for a "Reaganite policy of military strength and moral clarity." Basically, they wanted to spend more on defense and be way more aggressive in challenging regimes that didn't align with U.S. interests.

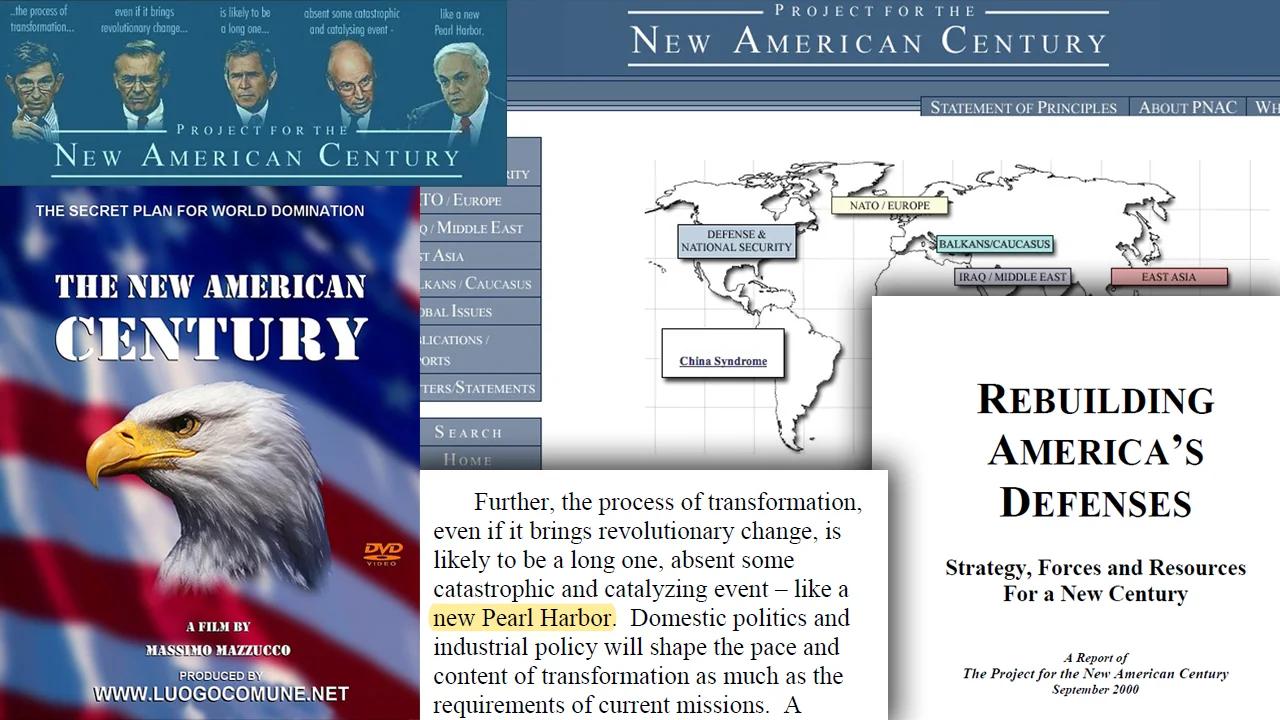

The "New Pearl Harbor" line that sparked a thousand theories

There is one specific line in a 2000 PNAC report titled Rebuilding America's Defenses that gets brought up constantly. The report argued that the process of transforming the U.S. military into a dominant 21st-century force would be a slow one, "absent some catastrophic and catalyzing event – like a new Pearl Harbor."

Then 9/11 happened.

👉 See also: Stuck in Traffic? What Really Happened With the Accident on 287 North Today

Conspiracy theorists jumped on this immediately. But if you look at the actual history, it's less about a "setup" and more about an ideological group seeing a window of opportunity. To PNAC, 9/11 wasn't something they planned; it was the "catalyzing event" they had already predicted would be necessary to convince the public to fund a massive military expansion. They were ready. They had the papers written. They just needed the public's permission to execute.

Why the Iraq War was the PNAC "North Star"

Long before George W. Bush took office, PNAC was obsessed with Saddam Hussein. In 1998, they sent an open letter to President Bill Clinton. They told him that "containment" wasn't working. They insisted that removing Saddam from power needed to be the aim of American foreign policy.

They weren't alone.

Congress passed the Iraq Liberation Act that same year. But PNAC provided the intellectual "why." They argued that a democratic Iraq would transform the Middle East. They saw it as a domino effect. Knock over the big guy, and the rest of the region would follow suit into a pro-Western, democratic future.

History, as we know, had other plans.

The war was longer, bloodier, and more expensive than any of the PNAC signatories predicted. Ken Adelman, a PNAC member, famously called the war a "cakewalk" in a Washington Post op-ed. That quote aged like milk. The complexity of sectarian violence and the lack of a "Day Two" plan turned the Project for the New American Century's dream into a geopolitical nightmare.

The fallout and the quiet closing of doors

By 2006, the brand was toxic. The "New American Century" was looking more like a century of quagmires and trillion-dollar deficits.

👉 See also: Eichmann in Jerusalem: Why Arendt's "Banality of Evil" Still Triggers Us

The organization didn't go out with a bang. It just sort of faded. Gary Schmitt, the former executive director, eventually admitted that the group had "run its course." They had achieved their primary goal—getting their people into power and enacting their policies—but the results were so polarizing that the organization itself couldn't survive the backlash.

But here’s the thing: the people didn't go away.

Even after PNAC officially folded in 2006, the "neoconservative" wing of the GOP remained a powerhouse. You saw its echoes in the Foreign Policy Initiative (FPI), which Kristol and Kagan also helped start. You see it today in the debates between the "America First" wing of the Republican party and the "Old Guard" who still believe in global intervention.

It wasn't just about war

People forget PNAC talked about more than just tanks. They were early advocates for:

- Space Force concepts: Long before the branch was created, they wrote about the need to control space as a military high ground.

- Cyber Warfare: They recognized that the next century would be fought in "bits and bytes."

- Missile Defense: They were obsessed with the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) and pushing it into the modern era.

What most people get wrong about PNAC

A lot of folks think PNAC was a "secret" group. It really wasn't. They published their letters on their website. They did interviews on C-SPAN. They were incredibly public about what they wanted.

The real story isn't a "conspiracy"; it's a story of ideological capture. It’s about how a small, focused group of intellectuals can provide a ready-made worldview to a government in a moment of crisis. When the planes hit the towers, the Bush administration didn't have to sit around wondering what to do. They just pulled the PNAC playbooks off the shelf.

Was it a failure?

Depends on who you ask. If the goal was "global stability," then yeah, it didn't go great. If the goal was to ensure the U.S. remained the undisputed military superpower with a presence in every corner of the globe, they largely succeeded. The U.S. defense budget today is a testament to the "Reaganite strength" they lobbied for in 1997.

Actionable insights for the modern observer

The era of the Project for the New American Century provides a massive lesson in how policy is actually made. It's rarely about a sudden whim of a President. It’s about "policy windows."

- Watch the Think Tanks: If you want to know what the government will do five years from now, don't look at the news; look at the white papers coming out of places like the Center for a New American Security (CNAS) or the Heritage Foundation today.

- The "Pearl Harbor" Factor: Be wary of policies that require a "catastrophic event" to become palatable. History shows that when these events happen, the pre-written plans are rarely tailored to the specific reality of the crisis.

- Ideology vs. Reality: PNAC’s biggest failure was assuming that "democracy" could be exported via military force. When analyzing modern foreign policy, ask if the proponents are accounting for local culture, history, and the "unknown unknowns."

- Follow the Signatories: Don't just look at organizations; look at the names. Many of the junior staffers from the PNAC era are now the senior advisors in today's political landscape.

The Project for the New American Century might be dead as a formal organization, but the DNA of its "benevolent global hegemony" still runs through the veins of American foreign policy. Understanding it isn't about looking at the past—it's about seeing the architecture of the present.

To really dig deeper, look up the 1992 "Defense Planning Guidance" draft written by Paul Wolfowitz. It's the "prequel" to PNAC and shows that these ideas were simmering for decades before they finally boiled over in 2003. Reading the primary sources directly—the letters to Clinton, the 2000 reports—is the only way to cut through the internet noise and see the strategy for what it actually was: a bold, risky, and ultimately transformative attempt to lock in American power forever.