You probably think of sugar as a chemical. A white, crystalline powder that just sort of appears in a bag at the grocery store. But honestly? It’s basically just dried-up grass juice. That’s the big secret. When you look at the process of sugarcane into sugar, you aren't looking at a synthetic laboratory miracle. You’re looking at a massive, muddy, industrial-scale version of making a cup of tea and letting it sit out until the water evaporates.

It starts in a field. Not just any field, but usually somewhere like the Everglades in Florida, the red soil of Brazil, or the monsoon-soaked plains of India. Sugarcane is a beast of a plant. It grows twelve feet high and is so tough it can cut your skin like a razor. Harvesting it is the first real hurdle. In many places, they still burn the fields first to get rid of the "trash"—the dead leaves and snakes—leaving only the stalks standing in a charred, blackened landscape.

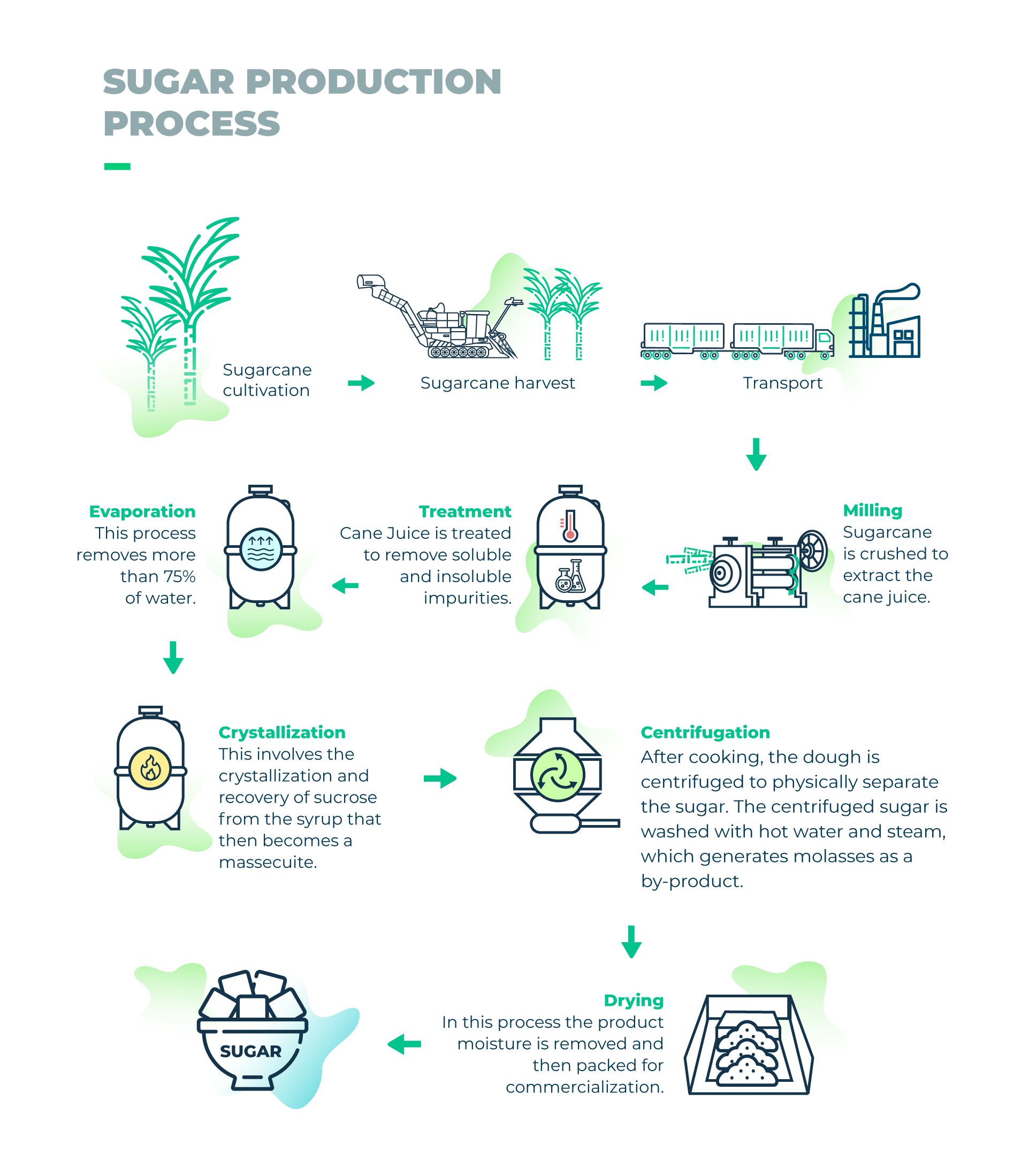

Crushing the Life Out of It

Once that cane is cut, the clock starts ticking. Fast. If you let harvested sugarcane sit for more than a day or two, the sucrose starts breaking down into "invert sugars." Basically, the plant starts eating its own sweetness. This is why sugar mills are always built right in the middle of the fields. You’ve seen those massive trucks overflowing with green and brown stalks? They are in a literal race against fermentation.

At the mill, the stalks are dumped into a series of massive, grooved rollers. These things are terrifying. They apply tons of pressure to squeeze every drop of liquid out. This raw juice is a murky, grey-green soup. It tastes like sweet grass and earth. It is definitely not something you’d want to put in your coffee yet.

While the juice moves one way, the leftover fiber—called bagasse—moves the other. This is where the process gets smart. Most modern mills don't buy electricity. They burn the bagasse in massive boilers to create steam. That steam turns turbines to run the mill. It’s a self-sustaining cycle that makes the sugar industry one of the original "green" energy pioneers, even if the smoke from the chimneys looks anything but green.

The Chemistry of Cleaning Up

Now you’ve got this giant tank of dirty juice. You can't just boil it. It's full of soil, bits of plant, and organic acids that would ruin the crystallization. This is where the process of sugarcane into sugar turns into a chemistry experiment.

Engineers add "milk of lime" (calcium hydroxide) to the juice. This raises the pH. In its natural state, the juice is slightly acidic. If you leave it that way, the sugar won't crystalize properly. The lime reacts with the impurities, and then they blow carbon dioxide through the mix. This creates tiny flakes of calcium carbonate—basically limestone—that grab onto all the dirt and sink to the bottom of the tank.

Why Your Sugar Isn't Always Vegan

Here is a detail that weirds people out. Some refineries, especially older ones or those producing specific types of white sugar, use bone char as a filter. It's exactly what it sounds like: charred cattle bones. It is an incredible decolorizer. It strips the yellow and brown tints out of the syrup better than almost anything else. If you are a strict vegan, you usually look for "certified organic" or "beet sugar" because those almost never touch bone char. But for standard cane sugar? It's a common part of the purification step in the final refining stages.

Boiling It Down to the Grit

After it's cleaned, the juice is mostly water. About 85% water, actually. To get sugar, you have to get rid of that liquid. But you can't just boil it on a high flame like you're making pasta. If you get sugar too hot, it carmelizes. It turns brown and tastes like burnt candy. Great for flan, terrible for white table sugar.

The solution is a vacuum.

By lowering the air pressure inside massive steel vessels called evaporators, the mill can make the juice boil at a much lower temperature. This saves energy and protects the sucrose molecules. The juice thickens into a heavy, dark syrup called "macerite" or just "thick juice."

Then comes the "seeding." This is the part that feels like magic. A technician drops a tiny amount of finely ground sugar dust into the syrup. These tiny specks act as a foundation. The dissolved sugar in the syrup sees these solid crystals and starts grabbing onto them. They grow. Within hours, the tank is no longer full of liquid; it’s a thick, gritty sludge called massecuite.

The Spin Cycle

How do you get the crystals out of that sludge? You spin them. Fast.

The massecuite goes into a centrifuge. Think of it like a giant washing machine on the spin cycle, but way more violent. The liquid—which we know as molasses—is flung through the holes in the drum. The solid sugar crystals stay trapped against the walls.

✨ Don't miss: Bulldog Type Representative Species: What You Actually Need to Know About This Stubborn Family

- Raw Sugar: This is what comes out of the first spin. It’s light brown, slightly sticky, and tastes like honey and earth.

- Refined Sugar: This happens when the raw sugar is sent to a secondary refinery, melted down again, filtered even more, and spun a second time.

- Brown Sugar: Most modern brown sugar is actually just white sugar that has had a little bit of molasses sprayed back onto it.

The Molasses Paradox

People often think molasses is a "health food" alternative. It’s complicated. Molasses is essentially the concentrated "waste" of the sugar process. It contains all the minerals and vitamins that the plant pulled from the soil—things like iron, magnesium, and potassium—which the white sugar crystals left behind.

Blackstrap molasses is the result of the third and final boiling. It’s bitter. It’s thick. It’s packed with nutrients. But it’s also the stuff that didn't make the cut for the sugar bowl. In many parts of the world, this is used mostly for animal feed or fermented into rum. Without the sugar process, we wouldn't have the global rum industry. It’s all interconnected.

Why the Process is Changing

We are seeing a shift in how the process of sugarcane into sugar works because of climate change and labor costs. In places like Australia and Louisiana, mechanical harvesters have almost entirely replaced the "man with a machete" image. These machines are incredible—they cut the cane, chop it into small pieces (billets), and blow the trash back onto the field as mulch.

This mulch is important. It keeps the moisture in the soil. It reduces the need for chemical fertilizers.

Also, there is a massive push for "Low GI" sugar. Brands like Nucane have developed a way to keep more of the natural polyphenols in the sugar during the milling process. These antioxidants slow down how fast your body absorbs the glucose. It’s still sugar, but it doesn't give you that massive "crash" that highly refined white sugar does.

🔗 Read more: How to Make a Naked Photo: Lighting, Safety, and Why Everyone Gets It Wrong

What This Means For Your Kitchen

Understanding this process actually makes you a better baker. If you know that sugar is a crystal that wants to stay a crystal, you understand why you need "interference agents" like corn syrup or lemon juice when making caramel. You are fighting the natural tendency of that grass juice to return to its solid, gritty state.

If you want to use this knowledge practically, start looking at the labels. "Evaporated cane juice" is just a fancy marketing term for sugar that hasn't been refined as much. It’s essentially the stuff that came out of the first centrifuge. It has a deeper flavor because those tiny bits of plant minerals are still clinging to the crystal.

Actionable Steps for the Conscious Consumer:

- Check the source: If you want to avoid bone char, look for sugar labeled "USDA Organic" or "100% Pure Beet Sugar." Beets are processed in a single facility and never require bone char for whitening.

- Store it right: Sugar doesn't "spoil" in the traditional sense because bacteria can't grow on it (it sucks the moisture out of them), but it will absorb smells. Keep it in an airtight glass jar away from your spice rack unless you want cumin-scented cookies.

- Revive the brown: If your brown sugar is a brick, don't throw it out. The molasses has just dried up. Put a piece of bread or a damp paper towel in the container for 24 hours. The sugar will pull the moisture out of the bread and become soft again.

- Experiment with "Raw": Try using Turbinado or Muscovado sugar in your coffee. These are "first-spin" sugars. They have a higher moisture content and a much more complex flavor profile than the white stuff.

The journey from a 12-foot stalk of grass to a teaspoon of white crystals is an incredible feat of engineering. It’s a mix of ancient farming, Victorian-era steam power, and modern centrifugal physics. Next time you stir a spoonful into your tea, remember that it's basically just the sun's energy, captured by a leaf and squeezed out by a giant machine.