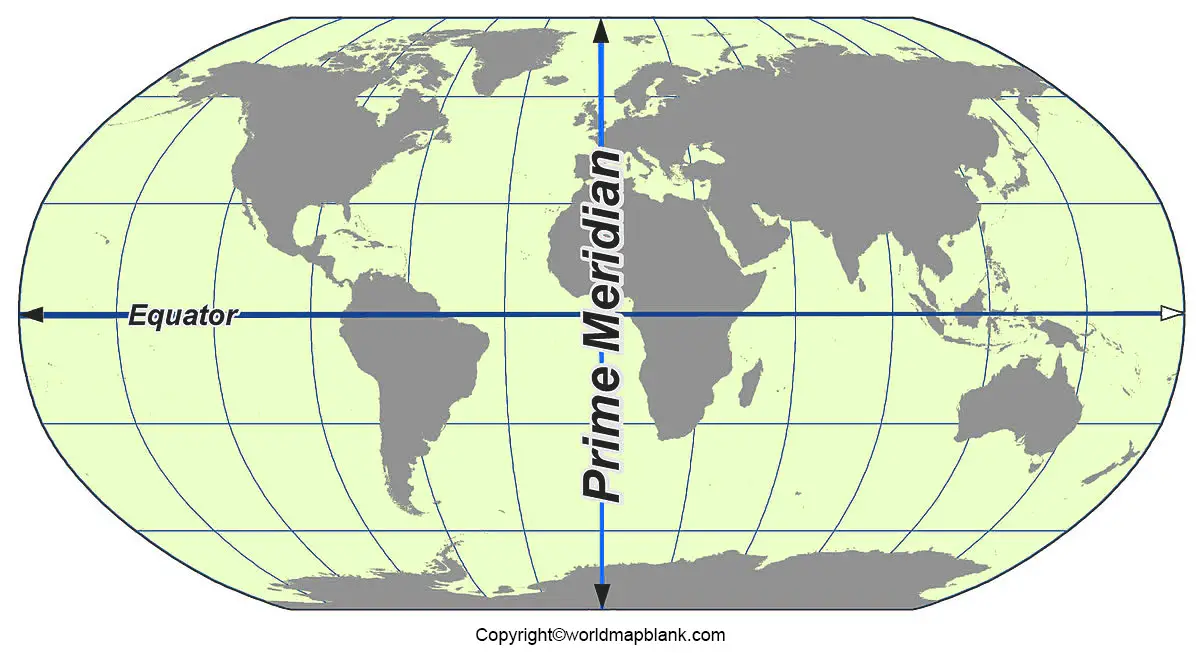

Ever looked at a map and wondered why London gets to be the center of the universe? Or at least, the center of time? That bold vertical line, the prime meridian on a world map, defines how we navigate, how we sync our watches, and how we understand our place on this spinning rock. It’s the zero-point. The "Start Here" button for longitude.

But here is the thing. It’s totally arbitrary.

Nature gave us the Equator. The Earth spins on an axis, so the Equator is a physical reality—a middle ground between the poles. Longitude? That’s just a human invention. We could have put the prime meridian through Paris, Kyoto, or even a random Shack in Nebraska. For a long time, people actually did use different spots. Navigating the seas was a chaotic mess of competing "zeros" until everyone finally agreed to settle on a small neighborhood in South East London.

The Greenwich Power Play

If you visit the Royal Observatory in Greenwich today, you can literally stand with one foot in the Eastern Hemisphere and one in the Western. It's a great photo op. But why there? Why did a tiny hill in London become the anchor for the prime meridian on a world map?

It wasn't because of some mystical geographical energy. It was mostly about ships and money. By the late 1800s, the British Empire was the dominant maritime power. Most of the world’s charts were already using Greenwich as their reference point because the British Admiralty produced the most reliable nautical almanacs.

In 1884, 41 delegates from 25 nations met in Washington, D.C., for the International Meridian Conference. They needed a single, unified system. Before this, you had the "Paris Meridian" and the "Ferro Meridian." Imagine trying to coordinate a train schedule or a shipping route when every country thinks "noon" happens at a different time. It was a nightmare.

The vote for Greenwich wasn't even close. 22 countries voted yes. Tiny San Domingo (now the Dominican Republic) voted no. France and Brazil played hardball and abstained. The French, in particular, were annoyed. They kept using their own "Paris Meridian" for another few decades before finally caving in 1911. They didn't even call it Greenwich Time at first; they called it "Paris Mean Time retarded by 9 minutes and 21 seconds."

Spite is a powerful motivator in cartography.

👉 See also: Campbell Hall Virginia Tech Explained (Simply)

Wait, the Line Moved?

If you take your high-tech smartphone to the "official" stainless steel strip at Greenwich, you’ll notice something annoying. Your GPS will tell you that you aren't at $0^{\circ} 0' 0''$.

You’re actually about 102 meters (roughly 334 feet) east of the line.

This isn't a glitch in your phone. And the brass rail isn't "wrong" in a historical sense. It’s just that our tech got better than our telescopes. The original 1884 line was calculated using a "transit circle" telescope. Sir George Airy, the Astronomer Royal, used it to track the movement of stars. But he didn't account for the fact that Earth isn't a perfect sphere and that local gravity can slightly deflect a plumb line.

Modern satellites use the WGS84 (World Geodetic System 1984) coordinate system. It uses the Earth's center of mass as its reference point. Because of the way the Earth’s mass is distributed, the "Reference Meridian" used by GPS shifted slightly away from Airy’s old telescope.

Basically, the prime meridian on a world map is a ghost. It's a mathematical concept that doesn't care about brass strips in the pavement.

Why Longitude Was a Death Sentence

We take the prime meridian on a world map for granted now. But for centuries, not knowing your longitude meant you were probably going to crash your ship into a reef and die.

Finding latitude is easy. You look at the sun or the North Star. Finding longitude is hard. It requires knowing exactly what time it is at your "home" port while you are in the middle of the Atlantic. Every four minutes of time error equals one degree of longitude error. In the tropics, that’s about 68 miles.

✨ Don't miss: Burnsville Minnesota United States: Why This South Metro Hub Isn't Just Another Suburb

The British "Longitude Act" of 1714 offered a massive prize—£20,000—to anyone who could solve the problem. A self-taught clockmaker named John Harrison finally figured it out with his "marine chronometers." These were clocks that didn't lose time on a rocking, humid ship. Because his work was centered at Greenwich, the Greenwich line became the gold standard for every sailor with a Harrison-style clock.

This is why we talk about GMT (Greenwich Mean Time). It’s the heartbeat of the planet. Even in the age of Atomic Clocks and Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), Greenwich remains the spiritual home of "Zero."

The Impact on Your Daily Life

You might think the prime meridian on a world map is just for geography nerds or pilots.

Wrong.

It dictates your life every single day.

- Time Zones: The world is divided into 24 time zones, each theoretically 15 degrees of longitude wide. Everything is an offset of the prime meridian.

- The International Date Line: Directly opposite the prime meridian ($180^{\circ}$) is the International Date Line. Without the zero at Greenwich, we wouldn't know when today becomes tomorrow.

- Aviation: Pilots don't use local time for flight plans. They use "Zulu" time, which is just another name for the time at the prime meridian. This prevents mid-air collisions that might happen if two planes were using different local offsets.

- The Internet: Servers often sync to UTC. When you buy a concert ticket the second it goes on sale, the backend logic is likely using a timestamp rooted in the prime meridian's logic to ensure fairness across global time zones.

How to Find It and Use It

If you're looking at a prime meridian on a world map, you're looking at the vertical axis. Most digital maps like Google Maps or Apple Maps don't draw a giant bold line for it unless you're zoomed out or have grid lines turned on.

To see it clearly, look for Western Europe and Western Africa. The line passes through:

🔗 Read more: Bridal Hairstyles Long Hair: What Most People Get Wrong About Your Wedding Day Look

- United Kingdom (Greenwich)

- France

- Spain

- Algeria

- Mali

- Burkina Faso

- Togo

- Ghana

- Antarctica (The South Pole)

Most people assume the line is "straight" through the ocean, and it is. But the International Date Line on the other side of the world zigs and zags to avoid splitting countries in half. The prime meridian is much more disciplined. It cuts right through Ghana and Spain without a care in the world.

If you are a traveler, visiting the line in Tema, Ghana, is often more "pure" than Greenwich because it's closer to the intersection with the Equator. That spot—where $0^{\circ}$ latitude meets $0^{\circ}$ longitude—is in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. It’s called "Null Island." There’s nothing there but a weather buoy, yet it’s one of the most famous places in digital mapping because that’s where computers put you when they have no idea where your coordinates are.

Actionable Steps for Map Lovers

Understanding the prime meridian on a world map makes you a better navigator and a more informed global citizen. Here is how to actually apply this knowledge:

1. Fix Your GPS Expectations

If you visit Greenwich, don't get mad when your phone says you aren't at zero. Accept the 102-meter offset as a lesson in the evolution of science. The brass line is history; the phone is math.

2. Learn the Offsets

Stop googling "what time is it in Tokyo." If you know Tokyo is roughly $139^{\circ}$ East, you can estimate it's about 9 hours ahead of the prime meridian ($139 / 15 \approx 9$). It makes you feel like a wizard.

3. Check Your Map Projection

The prime meridian on a world map looks different depending on the projection. On a Mercator map (the one that makes Greenland look huge), it’s a straight vertical line. On a Gall-Peters or a Robinson projection, it might be the only straight vertical line while the others curve. Recognizing the prime meridian helps you see how a map is distorting the world.

4. Explore Null Island

If you work in data or GIS, keep an eye out for "0,0" in your datasets. It’s almost always a mistake where the software defaulted to the intersection of the prime meridian and the equator. Knowing this prevents massive data errors in business or logistics.

The line is imaginary. We made it up in a room in 1884. But it is the scaffolding that holds the modern world together. Without it, we are just lost in time.