Hollywood usually breaks things when they try to fix them. We've all seen it. A studio takes a black-and-white classic, sprinkles some modern CGI dust on it, hires a "bankable" lead, and the whole thing collapses under the weight of its own lack of soul. But when we talk about the remake of The Bishop’s Wife, things get interesting. Most people know it as The Preacher’s Wife.

It arrived in 1996. It had Denzel Washington. It had Whitney Houston.

Honestly, the stakes were impossibly high. The 1947 original wasn't just some movie; it was a Cary Grant vehicle that defined the post-war holiday spirit. It was light, ethereal, and arguably perfect. Attempting to recapture that magic almost fifty years later seemed like a fool's errand. Yet, the 1996 version didn't just copy-paste the script. It shifted the perspective, leaned into the gospel tradition, and somehow created a film that stands on its own two feet today.

The Massive Shadow of 1947

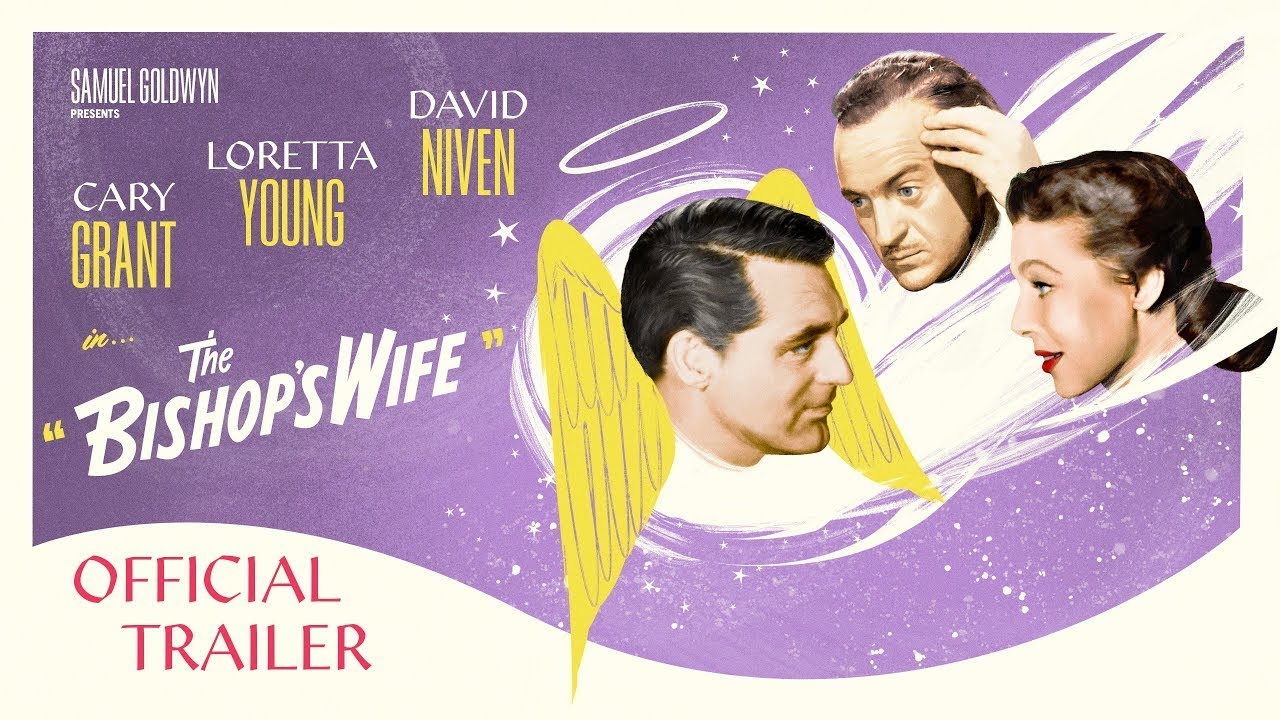

To understand why the remake of The Bishop’s Wife matters, you have to look at the source material. The 1947 film featured Cary Grant as Dudley, an angel sent to help Bishop Henry Brougham (David Niven) and his wife Julia (Loretta Young). Henry is obsessed with building a massive cathedral. He’s lost his way. He’s ignored his family.

Grant’s Dudley was suave. He was charming in that "I’m a movie star who happens to be an angel" kind of way. It was a fantasy about the upper-middle class and their polite spiritual crises.

Then 1996 happened.

Penny Marshall, the director, took a different route. She didn't want a carbon copy. She moved the setting from a wealthy, snowy parish to a struggling inner-city church in New Jersey. The "Bishop" became Reverend Henry Biggs, played by Courtney B. Vance. The stakes weren't just about a fancy building anymore; they were about the survival of a community.

Denzel Washington vs. Cary Grant: The Angel Dilemma

Denzel Washington had a problem. How do you follow Cary Grant without looking like you’re doing a bad impression?

💡 You might also like: Kiss My Eyes and Lay Me to Sleep: The Dark Folklore of a Viral Lullaby

He didn't try.

In the remake of The Bishop’s Wife, Denzel’s Dudley is playful, almost mischievous. He brings a human warmth that Grant’s version—as perfect as it was—sometimes lacked. Grant was an icon of perfection. Denzel was a guy you’d actually want to grab a coffee with, even if he did have celestial powers.

There’s a specific chemistry shift here. In the original, the tension between Dudley and Julia felt like a sophisticated ballroom dance. In the remake, Denzel and Whitney Houston had a vibe that felt dangerous in a way a church-centered movie rarely allows. You actually wonder, for a second, if this angel might just forget his heavenly duties and stay for the girl. That’s a testament to the acting, but also to a script that understood 1990s audiences wanted a bit more "will-they-won't-they" heat.

Whitney Houston and the Power of the Soundtrack

You can’t talk about the remake of The Bishop’s Wife without talking about the voice.

The 1947 version had a nice score. It was fine. It was very "Golden Age of Hollywood."

The 1996 version, however, is basically a vessel for one of the greatest gospel albums of all time. Whitney Houston was at the absolute peak of her powers. Songs like "I Believe in You and Me" and "Step by Step" didn't just sit in the background. They drove the narrative. The music became the spiritual backbone of the film, replacing the somewhat stiff religious themes of the original with something visceral and loud.

The soundtrack actually remains the best-selling gospel album of all time. Think about that. A remake of a 1940s fantasy film produced a record that sold over six million copies. That doesn't happen by accident. It happened because Penny Marshall recognized that to make the story relevant to a modern (at the time) audience, the "soul" of the film had to be literal.

📖 Related: Kate Moss Family Guy: What Most People Get Wrong About That Cutaway

Why the Change in Title Matters

Why isn't it just called The Bishop’s Wife?

Marketing, sure. But there’s a theological and cultural nuance there. In the African American church tradition, the title "First Lady" or "Preacher's Wife" carries a specific weight and social expectation. By renaming it The Preacher's Wife, the filmmakers signaled that this wasn't just a story about a man’s mid-life crisis. It was about Julia’s life, her voice, and her role in a community that was being squeezed by urban decay and corporate greed (personified by Gregory Hines’ character).

The Script’s Subtle Surgery

If you watch them side-by-side, the plot beats of the remake of The Bishop’s Wife are strikingly similar to the original.

- A man of God prays for help.

- An angel arrives but doesn't immediately reveal his identity.

- The angel spends more time with the wife than the husband.

- Jealousy ensues.

- The angel fixes the community and leaves, with no one remembering he was there.

But the remake adds a layer of social commentary. In the 1947 version, the "villain" is essentially Henry’s own ego and a wealthy widow who wants to control the church's design. In the 1996 version, the villain is Joe Hamilton, a developer who wants to tear down the church to build luxury condos.

It’s a classic David vs. Goliath setup. It makes the "miracles" feel more necessary. When Dudley helps the youth choir or fixes the boiler, it’s not just a whimsical trick; it’s a survival tactic for a neighborhood on the brink.

Critics and the "Cozy" Factor

Critics weren't all sold on it back in '96. Some felt it was too sugary. Some missed the crisp, dry wit of the original. Roger Ebert actually gave it a decent review, noting that it was a "sweet-tempered" movie that relied heavily on the charisma of its leads.

And he was right.

👉 See also: Blink-182 Mark Hoppus: What Most People Get Wrong About His 2026 Comeback

This isn't The Godfather. It’s a comfort movie. It’s meant to be watched with a blanket and a cup of cocoa. The remake of The Bishop’s Wife succeeded because it leaned into that "cozy" factor without becoming completely mindless. It’s a movie about the exhaustion of trying to do good in a world that values profit. That’s a theme that actually resonates more in 2026 than it did in 1996.

Fact-Checking the Production

There are a few things people get wrong about this movie.

- The Director: A lot of people forget Penny Marshall directed this. It was a huge departure from A League of Their Own or Big, but you can see her touch in the way she handles the ensemble cast.

- The Casting: Denzel wasn't the first choice. Initially, there were talks about different pairings, but once Whitney was on board, the search for a lead who could match her presence became paramount.

- The Location: While the original was filmed mostly on sets in Los Angeles (despite the winter setting), the remake used locations in New York and New Jersey to get that gritty, authentic cold-weather feel.

The Legacy of the Remake

Is the remake of The Bishop’s Wife better than the original?

That’s a trap question. They serve different masters. The 1947 film is a masterpiece of the studio system—a perfectly paced, witty, and slightly cynical look at faith. The 1996 film is a cultural touchstone for a different demographic. It brought the story to a Black audience that rarely saw themselves reflected in "prestige" holiday fantasies.

It also served as a reminder of Whitney Houston’s screen presence. For many, this is the film where she looked the most vibrant and felt the most "at home," likely because of her real-life roots in the church.

Key Takeaways for Film Buffs

If you’re planning a double feature, keep these things in mind:

- Watch the eyes. Cary Grant plays Dudley with a "knowing" twinkle. Denzel plays him with a "longing" look. It changes the whole vibe of the angel-human relationship.

- Listen to the silence. The 1947 version uses silence and dialogue to build tension. The 1996 version uses music to release it.

- Notice the children. The role of the children in both films is crucial. They are the first to "see" the angel for who he is, a classic trope that both directors use to signal the angel’s purity.

How to Appreciate the Remake Today

To truly get the most out of the remake of The Bishop’s Wife, stop comparing it to the original for five minutes. Look at it as a mid-90s time capsule.

Practical Steps for Your Next Viewing:

- Seek out the 4K restoration: Both films have been cleaned up recently. The colors in the 1996 version—the deep reds and blues of the church—are stunning.

- Listen to the soundtrack first: Put on the Whitney Houston album before you hit play. It sets the emotional stage better than any trailer ever could.

- Check the credits: Look at the supporting cast. People like Loretta Devine and Cedric the Entertainer (in a small role) provide the texture that makes the world feel lived-in.

- Compare the "Skaters" scene: Both movies have a famous ice-skating scene. The 1947 version is a feat of technical grace; the 1996 version is a masterclass in joyous chemistry.

The remake of The Bishop’s Wife didn't replace the original. It expanded the room. It took a story about a man losing his way and turned it into a story about a community finding its voice. In a world of lazy reboots, that’s a miracle in itself.