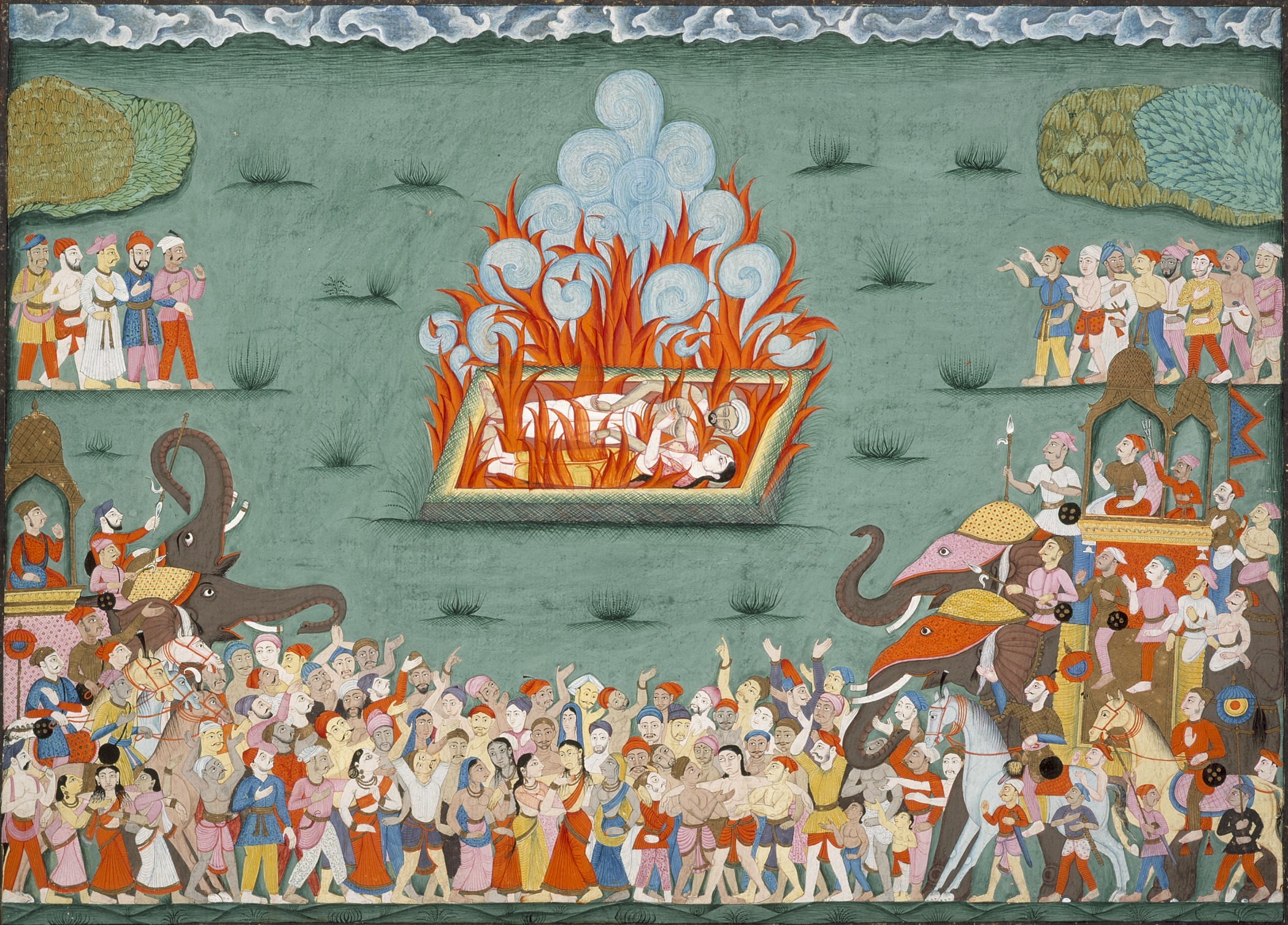

It is a haunting image. A widow, often young, sits atop her husband’s funeral pyre as the flames begin to rise. This is the practice of sati, a historical ritual in India that has sparked centuries of debate, horror, and complex sociological study. Most people think they know what it is—a simple case of forced religious martyrdom—but the reality is a lot more tangled and, frankly, much darker than just "tradition."

History isn't a straight line.

When you look at the practice of sati, you aren't just looking at a religious act; you're looking at a collision of property laws, colonial politics, and genuine, if misplaced, devotion. It wasn't ever "one thing." In some eras, it was a rare exception for the elite. In others, particularly during the 18th and 19th centuries in Bengal, it became a terrifyingly frequent occurrence.

Defining the Practice of Sati Beyond the Myths

Let’s get the basics down first. The word Sati (or Suttee) actually comes from the Sanskrit word for "virtuous woman." It refers to the Goddess Sati, who immolated herself because she couldn't stand the insult her father gave to her husband, Shiva. But here’s the kicker: in the mythology, Sati didn't die on her husband's funeral pyre. Shiva wasn't even dead! She died to protect his honor.

Over time, the term shifted from the person to the act itself.

By the time the British East India Company started poking around, the practice of sati was understood as a widow sacrificing herself on her husband’s pyre. If she did this, she was supposedly guaranteed to bring seven generations of her family to heaven. That’s a heavy weight to put on a grieving woman's shoulders. Honestly, it’s a lot of pressure.

Some accounts from the Gupta period (around 300-600 CE) mention it, but it wasn't a widespread "must-do" thing back then. It was localized. It was specific. You’d see it among the Rajput warrior clans where "Jauhar" (mass self-immolation to avoid capture by invaders) was a thing, but that’s technically a different branch of the same grim tree.

✨ Don't miss: 61 Fahrenheit to Celsius: Why This Specific Number Matters More Than You Think

Why Did It Happen? It Wasn’t Just Religion

If you think this was purely about faith, you’re missing the point. Economics played a massive role.

In Bengal, under the Dayabhaga system of law, widows actually had certain rights to their husband’s property. Think about that for a second. If a widow stays alive, she keeps the land or the money. If she dies on the pyre, that wealth stays with the brothers or the sons. You don't have to be a cynic to see the incentive there. It’s a brutal reality of how inheritance laws can literally kill.

The Colonial Lens

Then came the British. They were obsessed with it.

They used the practice of sati as a moral justification for their rule. "We are here to civilize you," was the vibe they went for. But they were also terrified of causing a rebellion by banning it too early. So, for a long time, they just "regulated" it. They sent officials to make sure the woman wasn't drugged and was over 16. Imagine that job description.

Raja Ram Mohan Roy, often called the "Father of Modern India," was the one who really pushed the needle. He had seen his own sister-in-law forced onto a pyre, and he was haunted by her screams. He didn't just argue from a "modern" perspective; he went back to the ancient Vedas to prove that the practice of sati wasn't even a mandatory part of Hinduism. He fought fire with scripture.

The 1829 Ban and the Roop Kanwar Case

In 1829, Lord William Bentinck finally banned it. It didn't vanish overnight, but it became a crime.

🔗 Read more: 5 feet 8 inches in cm: Why This Specific Height Tricky to Calculate Exactly

Fast forward to 1987.

Most people think of Sati as an ancient, "Middle Ages" problem. Then Roop Kanwar happened in the village of Deorala, Rajasthan. She was an 18-year-old girl who had been married for only eight months. She ended up on her husband's pyre in front of thousands of people. The fallout was massive. It led to the Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act, which made even "glorifying" the act a serious crime.

The Roop Kanwar case proved that the practice of sati wasn't just a ghost of the past. It was a lingering cultural trauma that could be triggered by specific social pressures and fundamentalist leanings. It forced India to look in the mirror and decide what kind of modern nation it wanted to be.

Sorting Fact from Fiction

You’ll hear some people claim that thousands of women were "jumping" into fires daily. That’s an exaggeration. Statistical records from the early 1800s suggest about 500 to 800 cases a year in the Bengal Presidency. Still way too many, but not a universal practice.

Others try to romanticize it as the ultimate expression of love.

Let's be real: when you look at the accounts of women being held down with long bamboo poles or drugged with opium so they wouldn't scream, the "romance" evaporates pretty quickly. There is a massive difference between a voluntary act and a socially coerced execution.

💡 You might also like: 2025 Year of What: Why the Wood Snake and Quantum Science are Running the Show

The Lasting Impact on Women's Rights

The fight against the practice of sati was the literal birthplace of the modern Indian women’s movement. It taught activists how to use the law, how to use the press, and how to challenge religious authorities.

It’s not just a "dead" tradition.

The mindset that a woman’s value is entirely tied to her husband is something that still lingers in various forms of social oppression today. Understanding the practice of sati is about understanding how societies control women’s bodies and their property.

How to Approach This History Today

If you're researching this, keep these things in mind:

- Check the Source: British colonial records are often biased to make themselves look like "saviors," while some nationalist records might downplay the horrors to protect "tradition."

- The Law Matters: Look into the Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987. It is one of the strictest laws in India for a reason.

- Context is King: Understand that "Sati" the goddess and "Sati" the ritual are two different things that got merged by history.

Moving Forward: Actionable Insights for the Curious

History shouldn't just be something we read; it should be something we learn from. If you want to dive deeper into the social structures that allowed the practice of sati to exist, there are specific steps you can take to understand the broader context of gender and law.

- Read Raja Ram Mohan Roy’s Tracts: Don't just take a textbook's word for it. Read his actual arguments from the 1820s. It’s fascinating to see how he used religious texts to dismantle a religious practice.

- Research the Dayabhaga vs. Mitakshara Systems: If you want to understand why Sati was more common in Bengal than in other parts of India, look at these two different inheritance systems. It explains the "why" behind the money.

- Support Modern Advocacy: Organizations like the All India Progressive Women's Association (AIPWA) continue to fight the cultural remnants of these practices. Supporting them is a way to turn historical knowledge into modern action.

- Visit the National Archives of India: If you’re ever in Delhi, the records from the 1820s provide a chilling, first-hand look at the "Sati Reports" filed by British officials. It’s a sobering experience.

The practice of sati is a dark chapter, but ignoring it or oversimplifying it does a disservice to the thousands of women who lived through it. By looking at the cold, hard facts—economic, legal, and social—we can ensure that "tradition" is never again used as a mask for violence.