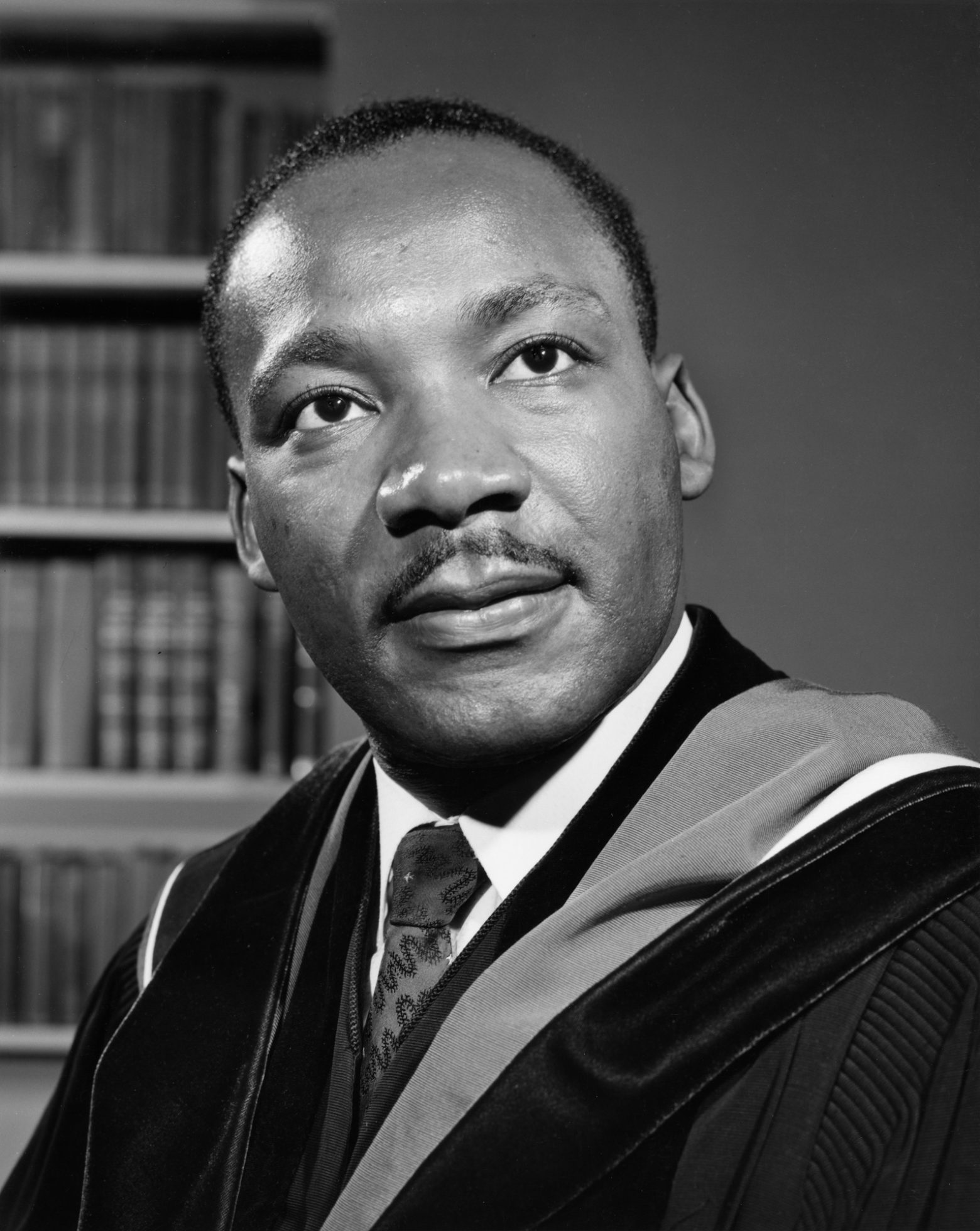

You know the one. He’s standing at a podium, jaw set, eyes focused on a horizon only he can see. Or maybe it’s the profile shot where he looks like a monument carved out of stone before he was even gone. Most people have a specific portrait of Martin Luther King Jr. burned into their retinas, usually from a grainy textbook or a social media post every January. But here’s the thing. Those photos, as iconic as they are, often flatten the man into a symbol. They turn a living, breathing, occasionally exhausted human being into a safe, static image.

Images matter. They aren't just snapshots; they are arguments.

When we look at a portrait of Martin Luther King Jr. today, we are seeing the result of decades of curation. We see the dreamer. We rarely see the man who was depressed, the man who joked with his staff to break the tension of constant death threats, or the man who looked genuinely tired of being the moral conscience of a country that didn't always want one. If you want to understand the civil rights movement, you have to look at how Dr. King was framed—literally and figuratively.

The Camera as a Tool of War

In the 1960s, photography wasn't just about art. It was a weapon. The SCLC (Southern Christian Leadership Conference) knew this better than anyone. They understood that a well-placed portrait of Martin Luther King Jr. could do more to move the needle in Washington than a thousand letters.

Take the work of Benedict Fernandez. He captured King in the final year of his life, specifically around 1967 and 1968. These aren't the "I Have a Dream" photos. In Fernandez’s work, King looks heavier. Not physically, but spiritually. There is a specific shot of him in a locker room, leaning against a wall, looking down. It’s a quiet, intimate portrait. You can see the weight of the Vietnam War opposition on his face. At that point, King was being attacked from all sides—the LBJ administration was furious with him, and younger activists thought he was moving too slowly.

That’s the portrait we need to see more of. It reminds us that courage isn't the absence of fatigue. It's doing the work when you’re bone-tired and the world is yelling at you.

Why the "Dreamer" Image Dominates Everything

Why do we keep seeing the same five photos? It’s basically about comfort.

The image of King smiling or looking peacefully resolute is easy to digest. It suggests that the "problem" was solved. When a gallery displays a portrait of Martin Luther King Jr. from the 1963 March on Washington, it feels triumphant. It fits a neat narrative of progress. But if you look at the portraits taken by Bob Adelman or Moneta Sleet Jr. during the Selma to Montgomery march, the vibe is different. You see the grit. You see the sweat.

👉 See also: Sport watch water resist explained: why 50 meters doesn't mean you can dive

Moneta Sleet Jr. actually became the first African American man to win a Pulitzer Prize for Journalism in 1969. He won it for his photograph of Coretta Scott King at her husband’s funeral. While that’s a portrait of her, King is there in the stillness, in the gravity of the grief. It’s a stark contrast to the vibrant, booming King we see on television specials.

Honestly, the way we consume these images says more about us than it does about him. We choose the portraits that make us feel like we’re on the right side of history without having to do the uncomfortable work King was actually demanding toward the end of his life, like addressing economic inequality and systemic poverty.

The Artistic Evolution of King’s Likeness

Beyond photography, the painted or sculpted portrait of Martin Luther King Jr. has its own weird, controversial history. You’ve probably seen the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial in Washington, D.C. It’s massive. It’s imposing. It’s also been heavily criticized.

The sculptor, Lei Yixin, carved King out of the "Stone of Hope." Some critics argued that the style was too reminiscent of "socialist realism"—the kind of art you’d see of Stalin or Mao. They felt it made King look too confrontational, too "stern." Others loved it for exactly that reason. They argued that King wasn't a "cuddly" figure; he was a radical who challenged the status quo.

Then you have the more contemporary interpretations. Artists today are moving away from the suit-and-tie rigidity. They’re using street art, vibrant acrylics, and even digital collage to reinvent what a portrait of Martin Luther King Jr. looks like for Gen Z and Gen Alpha. They’re adding color and context that wasn’t allowed in the 1960s press.

A Quick Reality Check on "Rare" Photos

You’ve probably seen those "rare" photos of King on your feed. Just a heads-up: most of them aren't actually rare. They are usually just from the archives of the High Museum of Art in Atlanta or the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

What's actually rare is seeing a photo of King where he isn't "on." He was a public figure who was almost always aware of the lens. Finding a portrait of Martin Luther King Jr. where he is genuinely unguarded—laughing at a dinner table or sitting in a moment of genuine doubt—is the real holy grail for historians.

✨ Don't miss: Pink White Nail Studio Secrets and Why Your Manicure Isn't Lasting

The Commercialization of the Image

It’s impossible to talk about King’s image without talking about copyright. The King Estate is notoriously protective. This is why you don't see his face on every random commercial product. While some people find this frustrating, it’s also a way to prevent his image from being completely diluted.

When you see a portrait of Martin Luther King Jr. in a high-end gallery or a documentary, it has likely been vetted. There is a deliberate effort to maintain the dignity of his likeness. But the downside is that it can make him feel untouchable. It turns him into a "brand" rather than a person. We have to balance that respect with the need to keep his humanity accessible.

He was a man who liked pool. He was a man who liked scanned-over notes and coffee. If we lose that in the portraits, we lose the most important lesson: that ordinary people can do extraordinary things.

How to View a Portrait Like a Historian

Next time you’re looking at an image of Dr. King, don’t just look at his face. Look at the background. Look at who is standing next to him.

Often, a portrait of Martin Luther King Jr. will crop out the women who were doing the heavy lifting behind the scenes. It might crop out the "unruly" protesters who didn't fit the suit-and-tie aesthetic the media wanted to project.

- Check the date: Was this before or after he came out against the Vietnam War? His face changes.

- Look at the hands: King’s hands were often expressive, holding a pen or gesturing for emphasis. They show his energy.

- Observe the lighting: Is he being depicted as a saint (halo-like lighting) or a worker?

The most "human" portraits are often the ones where he isn't looking at the camera. He’s looking at a colleague. He’s looking at a document. He’s just... being.

The Lasting Power of the Visual

The portrait of Martin Luther King Jr. remains one of the most recognizable images in human history. It rivals the Mona Lisa in terms of global saturation. But unlike a painting of a mysterious woman, King’s image carries the burden of a movement.

🔗 Read more: Hairstyles for women over 50 with round faces: What your stylist isn't telling you

It’s easy to get lost in the aesthetics. Don’t. The point of his portrait isn't to decorate a wall. It’s to remind us of the friction between what is and what should be.

If a portrait makes you feel too comfortable, it’s probably not telling the whole story. The best images of King are the ones that make you feel a little bit of the fire he felt. They should make you want to move, not just admire.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Understanding

If you want to move beyond the surface-level imagery, start by exploring the digital archives of the Library of Congress. Search for "Civil Rights Movement" rather than just King’s name to see the environment that shaped his face.

Another great move is to visit the National Civil Rights Museum at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis. Seeing the physical space where the final "portrait" of his life was taken—the balcony—changes how you view every other photo of him. It grounds the abstract symbol in a very real, very heavy reality.

Lastly, look into the work of Gordon Parks. His photography of the era provides the necessary contrast and context to understand how Black life in America was being documented alongside King’s rise. This helps you see King not as a solo act, but as part of a massive, complex tapestry of human struggle.