Georgia gardening is a wild ride. Honestly, if you've ever tried to keep a lavender plant alive in a humid Atlanta July or prayed your citrus wouldn't turn into an icicle in the Blue Ridge mountains, you know the struggle is real. It’s not just about the heat. It’s the weird, swinging pendulum of Southern weather. That's where the plant zone map Georgia gardeners rely on comes into play, but here’s the kicker: the map changed recently, and it changed a lot more than some people realize.

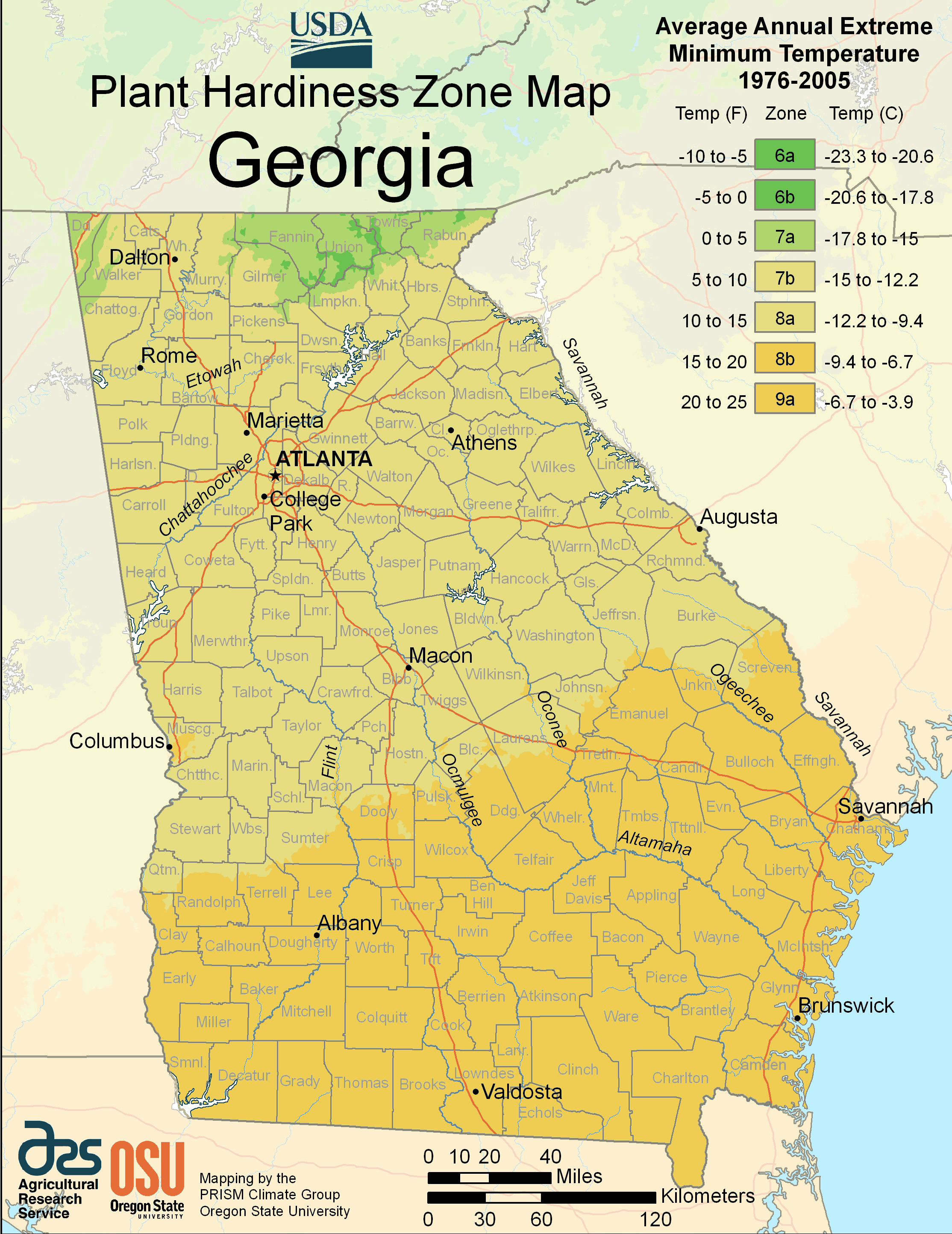

The USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map isn't just a colorful graphic for seed packets. It’s a data-driven snapshot of the coldest night of the year. For Georgia, a state that stretches from the literal Appalachian Trail down to the marshy Atlantic coast, those numbers tell a story of shifting climates. In late 2023, the USDA released its most significant update in over a decade. If you are still planting based on the 2012 map, you are basically gambling with your root systems.

Why the New Plant Zone Map Georgia Data Actually Matters

Most of Georgia shifted. We aren't talking about a tiny nudge; about half of the country moved up into a warmer half-zone, and the Peach State was right in the crosshairs of that shift.

You might think, "Great! I can finally grow lemons in Macon!" Well, maybe. But it’s more complicated than just getting warmer. The plant zone map Georgia uses is based on the average annual extreme minimum temperature. It doesn’t track how hot your summers get—which, let's be real, is usually what kills plants in Georgia—it only tracks how cold it gets before things start dying.

Specifically, the 2023 update incorporated data from over 13,000 weather stations. That is a massive jump from the 7,000 stations used in the previous version. This means the map is more granular. It picks up "urban heat islands" in places like downtown Atlanta or Savannah where concrete holds onto heat, making those micro-climates technically warmer than the surrounding suburbs.

The North Georgia Shift: Zones 7a to 8a

Up in the mountains, places like Blairsville or Blue Ridge used to be the chilly outliers. They were firmly in Zone 7. Now, much of that region has crept into Zone 7b. If you’re in the foothills or the Atlanta metro, you’ve likely migrated from 7b to 8a.

🔗 Read more: Finding the Right Word That Starts With AJ for Games and Everyday Writing

What does that mean for your backyard? It means your "average" coldest night is now somewhere between 10°F and 15°F, rather than 5°F to 10°F. Two-word summary: Less ice. But don't get cocky. Georgia is famous for "false springs." You’ll get a week of 70-degree weather in February that coaxes your azaleas into blooming, followed by a brutal frost that turns those blossoms into brown mush. The map tells you what can survive the winter, but it doesn't account for the chaotic timing of a Georgia freeze.

Central and South Georgia: Welcoming the Tropics?

As you move south of the fall line—think Columbus, Macon, and Augusta—the plant zone map Georgia reveals a definitive lean toward Zone 8b and even 9a.

Zone 9a used to be reserved for the very tip of the coast and the Florida border. Now, it’s pushing further inland. This is a game-changer for people wanting to grow things like Gardenias, certain types of palms, or even Oleander.

- Check your specific zip code on the USDA website. Do not guess.

- Look for the "b" vs "a" designation. "a" is the colder half of the zone; "b" is the warmer half.

- Don't throw away your frost blankets just because you moved up a zone.

University of Georgia (UGA) Extension experts often point out that while the map says we are getting warmer, our extremes are still violent. Remember the "flash freeze" of December 2022? Temperatures dropped 40 degrees in a matter of hours. A plant rated for Zone 8 might survive a steady 15°F, but it might not survive a 50-degree drop in one afternoon. The map is a guide, not a guarantee.

Soil and Drainage: The Silent Killers

Georgia’s red clay is legendary. It’s also a nightmare for drainage. If you’re looking at the plant zone map Georgia and thinking you can plant Mediterranean herbs because your zone is now warmer, stop. Those plants hate wet feet. During a soggy Georgia winter, that red clay holds water like a bathtub. A plant that could survive 15°F in dry soil will rot and die at 30°F if its roots are sitting in a frozen puddle of clay.

💡 You might also like: Is there actually a legal age to stay home alone? What parents need to know

You have to amend that soil. Compost, pine bark, and grit are your best friends. If you're in South Georgia, you deal with the opposite: sandy soil that loses nutrients faster than a leaky bucket. The map tells you the temperature, but the dirt tells you the truth.

The Myth of the "One Size Fits All" Georgia Garden

People often ask if they can grow "northern" plants like Peonies or Lilacs now. Honestly? It’s getting harder, not easier. These plants need "chill hours"—a specific amount of time spent under 45°F—to set buds. As the plant zone map Georgia shifts warmer, we are getting fewer chill hours.

If you live in Tifton or Valdosta, trying to grow a traditional lilac is basically a fool's errand. They’ll live, sure, but they won't bloom. They’ll just be leafy green disappointments. Instead, you have to look for "low-chill" varieties specifically bred for the Deep South.

Native Plants are the Real Cheat Code

If you want a garden that doesn't require a PhD and a constant IV drip of fertilizer, go native. Plants that have been in Georgia since before the Oglethorpe days don't care about a shift in the USDA map.

- Oakleaf Hydrangea: Unlike the finicky blue mopheads, these are tough as nails.

- Beautyberry: It’s purple, it’s weird, and birds love it.

- Native Azaleas: Skip the Big Box store hybrids and find the ones that actually belong here.

Practical Steps for Using the New Map

Stop looking at the back of the seed packet as the Gospel truth. Look at the map, then look at your specific yard. Do you have a north-facing slope that stays shady and icy? That’s a micro-zone. Is your patio tucked against a brick wall that soaks up sun all day? That’s another micro-zone.

📖 Related: The Long Haired Russian Cat Explained: Why the Siberian is Basically a Living Legend

Step 1: Identify your new number. Go to the USDA website and plug in your zip code. If you were 7b and now you're 8a, acknowledge that your "safety net" has moved.

Step 2: Audit your current perennials. Did anything struggle last winter? Did anything thrive? If your "hardy" shrubs are looking ragged, they might be reacting to the lack of a true dormant period rather than the cold itself.

Step 3: Mulch like your life depends on it. In Georgia, mulch isn't just for looks. It regulates soil temperature. It keeps the roots cool in the 100-degree August heat and insulated during a January cold snap. Two to three inches of pine straw or wood chips is the minimum.

Step 4: Water strategically. Most people stop watering in the winter. Big mistake. If a freeze is coming, water your plants deeply the day before. Moist soil stays warmer than dry soil and helps the plant withstand the desiccating winds of a cold front.

The plant zone map Georgia uses is a living document. It reflects a world that is getting warmer and weather that is getting more erratic. Use the data to pick your plants, but use your common sense to keep them alive. Watch the sky, touch your soil, and remember that in Georgia, the weather will always find a way to surprise you.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Zip Code Verification: Visit the USDA Agricultural Research Service website to confirm your specific 2023 zone designation, as many Georgia counties are now split between two zones.

- Plant Selection: When buying new trees or shrubs this season, choose species rated for at least one half-zone colder than your current location to provide a "buffer" against extreme weather events.

- Micro-Climate Mapping: Spend a weekend tracking the sun and wind patterns in your yard; use south-facing walls to plant "marginal" species like citrus or ginger that benefit from extra warmth.

- UGA Extension Resources: Utilize the University of Georgia's College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences database to find "low-chill" fruit varieties that match the decreasing chill hours in the updated Georgia climate.