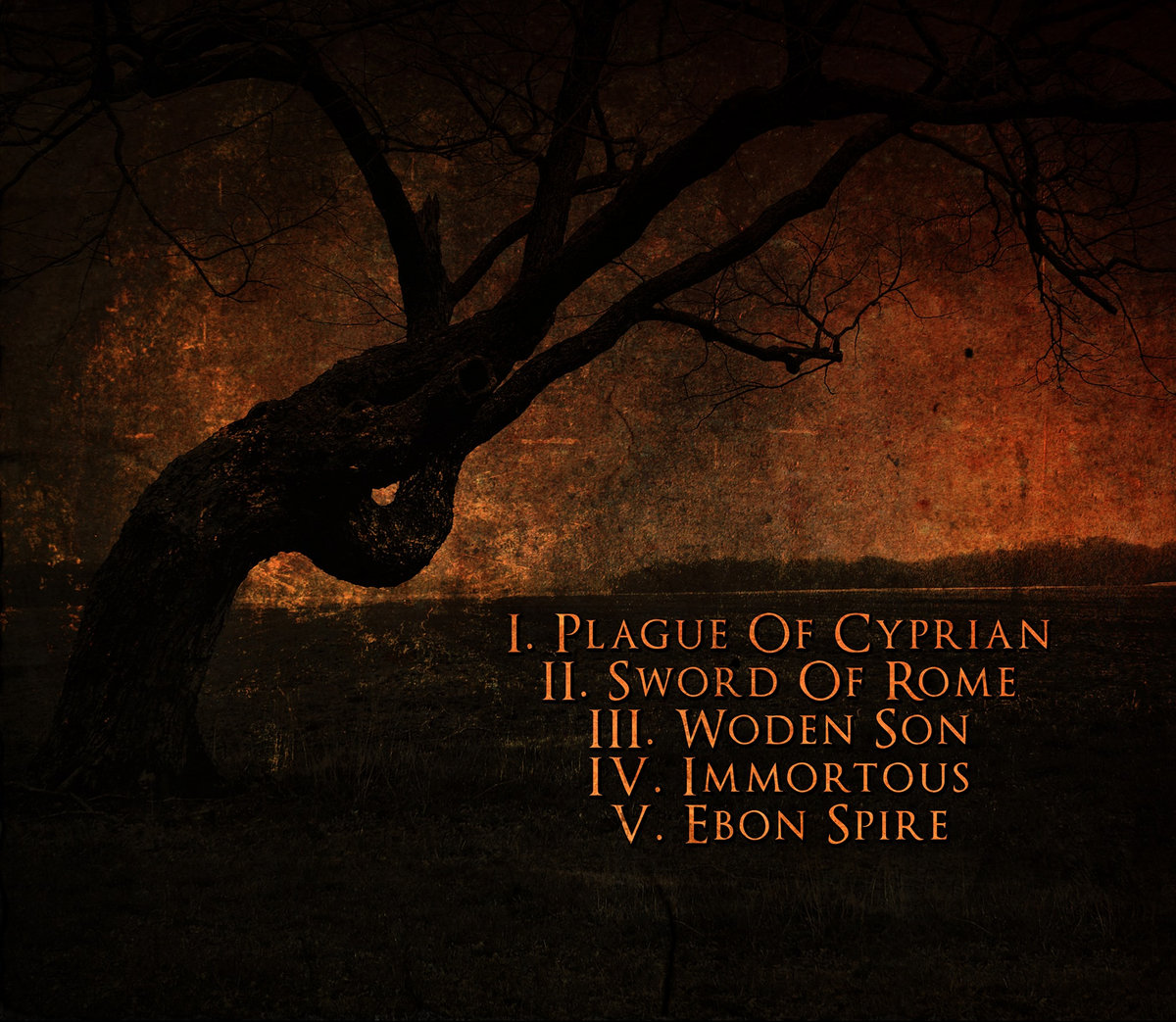

History is messy. People like to talk about the fall of Rome as if it was one big, dramatic crash, but it was really a series of punches to the gut that lasted centuries. One of the hardest hits? The Plague of Cyprian. It hit in the middle of the third century, right when the Roman Empire was already basically falling apart from civil wars and economic collapse.

It was brutal.

Imagine a city like Rome or Alexandria where 5,000 people are dying every single day. That isn't a "scary statistic" from a textbook; it was the reality for people living through it around 250 AD. This wasn't just a localized flu. It stretched from Ethiopia, up through Egypt, and across the entire Mediterranean. It lasted for nearly twenty years. Honestly, the fact that the Roman Empire survived the third century at all is a miracle given how many soldiers, farmers, and tax-paying citizens this disease wiped out.

What Was the Plague of Cyprian, Anyway?

You’ve probably heard of the Black Death. You might have heard of the Antonine Plague that happened a century earlier. But the Plague of Cyprian is the one that historians and scientists are still arguing about today. We call it "Cyprian" because of St. Cyprian, the Bishop of Carthage. He was the guy on the ground writing about it. He didn't just record the death toll; he described the symptoms in terrifyingly vivid detail.

He talked about the "bowels being relaxed into a constant flux" and the "fire that originates in the marrow" which burned the throat. People’s eyes were bloodshot. Their feet or parts of their limbs had to be amputated because of gangrene. They lost their hearing and their sight. It sounds like something out of a horror movie, but for the Romans, it was just Tuesday.

The Mystery of the Pathogen

Scientists are still trying to figure out what actually caused it. For a long time, people thought it was smallpox, mostly because the Antonine Plague was likely smallpox. But the symptoms don't quite line up. Smallpox usually involves a very specific kind of skin rash and pustules, which Cyprian doesn't focus on as much as the internal hemorrhaging and gastrointestinal failure.

Some modern researchers, like those who analyzed the "Funerary Complex of Harwa" in Luxor, Egypt, suggest it might have been a viral hemorrhagic fever. Think Ebola. That would explain the high contagion and the way it seemed to liquefy the internal organs of its victims. Others lean toward a severe strain of influenza or even a form of measles that was much more lethal than what we see today.

📖 Related: Why the EMS 20/20 Podcast is the Best Training You’re Not Getting in School

Back then, they didn't have microscopes. They didn't know about viruses. They thought the air was "corrupt." When you read Cyprian’s accounts, you realize he wasn't trying to be a doctor; he was trying to provide spiritual comfort to a population that thought the world was literally ending.

How the Disease Reshaped the World

The Plague of Cyprian didn't just kill people; it killed the way the world worked.

Think about the Roman army. It was the backbone of the empire. But a virus doesn't care about your military training or your rank. The plague ripped through the barracks. At one point, the Emperor Hostilian died from it in 251 AD. When your leader dies from a disease that is also killing your neighbors, the sense of "divine protection" over the state starts to vanish.

The economy took a nosedive too. No farmers meant no grain. No grain meant famine. No taxpayers meant the government couldn't pay the soldiers who hadn't died yet. It was a vicious cycle. The silver content in Roman coins dropped because the state was desperate to make their money stretch further. Inflation went through the roof.

It was a total systems failure.

- Labor Shortage: Large estates (latifundia) couldn't find enough workers to harvest crops.

- Urban Flight: People who could afford to leave the cities fled to the countryside, hoping to escape the "bad air."

- Military Weakness: Frontiers were left unguarded as legions were thinned out by sickness.

The Rise of Christianity Through the Chaos

One of the most fascinating things about the Plague of Cyprian is how it actually helped Christianity grow. At the time, Christians were a persecuted minority. But while the pagans were (understandably) terrified and often abandoned their sick relatives in the streets to save themselves, the Christians stayed.

👉 See also: High Protein in a Blood Test: What Most People Get Wrong

They saw it as a duty to care for the dying, regardless of whether they were Christian or not.

Cyprian himself told his followers that there was no merit in just loving their own. This "radical" idea of nursing the sick—providing water, food, and basic comfort—actually saved lives. Sometimes people just need a little hydration to survive a fever. Because the Christians stayed and provided that care, they had a much higher survival rate, and their neighbors noticed.

It changed the social fabric of the Empire. The "old gods" seemed powerless, while the Christian community seemed resilient and organized. This wasn't a sudden conversion, but the plague acted as a massive catalyst.

Comparing Cyprian to Other Pandemics

It’s easy to get these ancient plagues mixed up.

The Antonine Plague (165–180 AD) hit during the height of Roman power. It was bad, but the empire was strong enough to absorb the blow. The Plague of Cyprian hit when the empire was already on its knees. Later, the Plague of Justinian (541 AD) would involve the actual bubonic plague bacteria (Yersinia pestis), which is a different beast entirely.

Cyprian’s plague is unique because of its timing. It occurred during the "Crisis of the Third Century," a fifty-year period of near-constant civil war and barbarian invasions. If the plague hadn't happened, Rome might have stabilized much sooner. Instead, it faced a "perfect storm" of disasters.

✨ Don't miss: How to take out IUD: What your doctor might not tell you about the process

Lessons from the Ancient World

We can actually learn a lot from how the Romans handled (or failed to handle) this.

First, infrastructure matters. Rome’s incredible road system was great for trade, but it was also a superhighway for the Plague of Cyprian. The disease followed the trade routes perfectly. Once it hit a major port like Alexandria, it was only a matter of weeks before it showed up in Rome.

Second, the psychological toll is often just as heavy as the physical one. The writings from this era reflect a deep sense of nihilism. People stopped planning for the future. When you don't know if you'll be alive in a month, you don't plant crops or invest in businesses.

What Modern Science Tells Us

Archaeology is finally catching up to the written records. In the 2014 excavations at the Funerary Complex of Harwa in Thebes, archaeologists found bodies covered in a thick layer of lime. This was an ancient way of disinfecting. They also found large kilns where the victims were likely cremated in mass.

The presence of lime and mass disposals tells us that the authorities were overwhelmed. They weren't doing traditional burials anymore; they were just trying to stop the stench and the perceived "contagion."

Why We Still Talk About It

The Plague of Cyprian serves as a grim reminder of human vulnerability. It shows us that even the most powerful empire on Earth can be humbled by something invisible. It’s a story of collapse, but also of adaptation. The Roman Empire did eventually recover under leaders like Diocletian and Constantine, but it was a different version of Rome—more authoritarian, more bureaucratic, and eventually, Christian.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs and Researchers

If you're looking to understand this period better, don't just read history books. Look at the primary sources.

- Read "De Mortalitate" by Cyprian: It’s his treatise on the plague. It’s short, punchy, and gives you a direct window into the 3rd-century mindset.

- Compare the Symptoms: Look at the clinical descriptions provided by Cyprian and compare them to modern viral hemorrhagic fevers like Ebola or Marburg. It's a fascinating exercise in medical sleuthing.

- Track the Coinage: If you’re into economics, look at the "denarius" debasement charts from 240 AD to 270 AD. The drop in silver purity is a direct map of the empire’s desperation during the plague years.

- Explore Archaeological Reports: Follow the work of the Italian Archaeological Mission to Luxor (MAIL). Their findings at the Harwa complex are the closest we’ve come to "seeing" the plague's impact on the ground.

The Plague of Cyprian wasn't just a medical event; it was a turning point for Western civilization. It broke the old world and forced a new one to grow in its place. Understanding it helps us understand how societies handle extreme pressure—and who they become when the fever finally breaks.