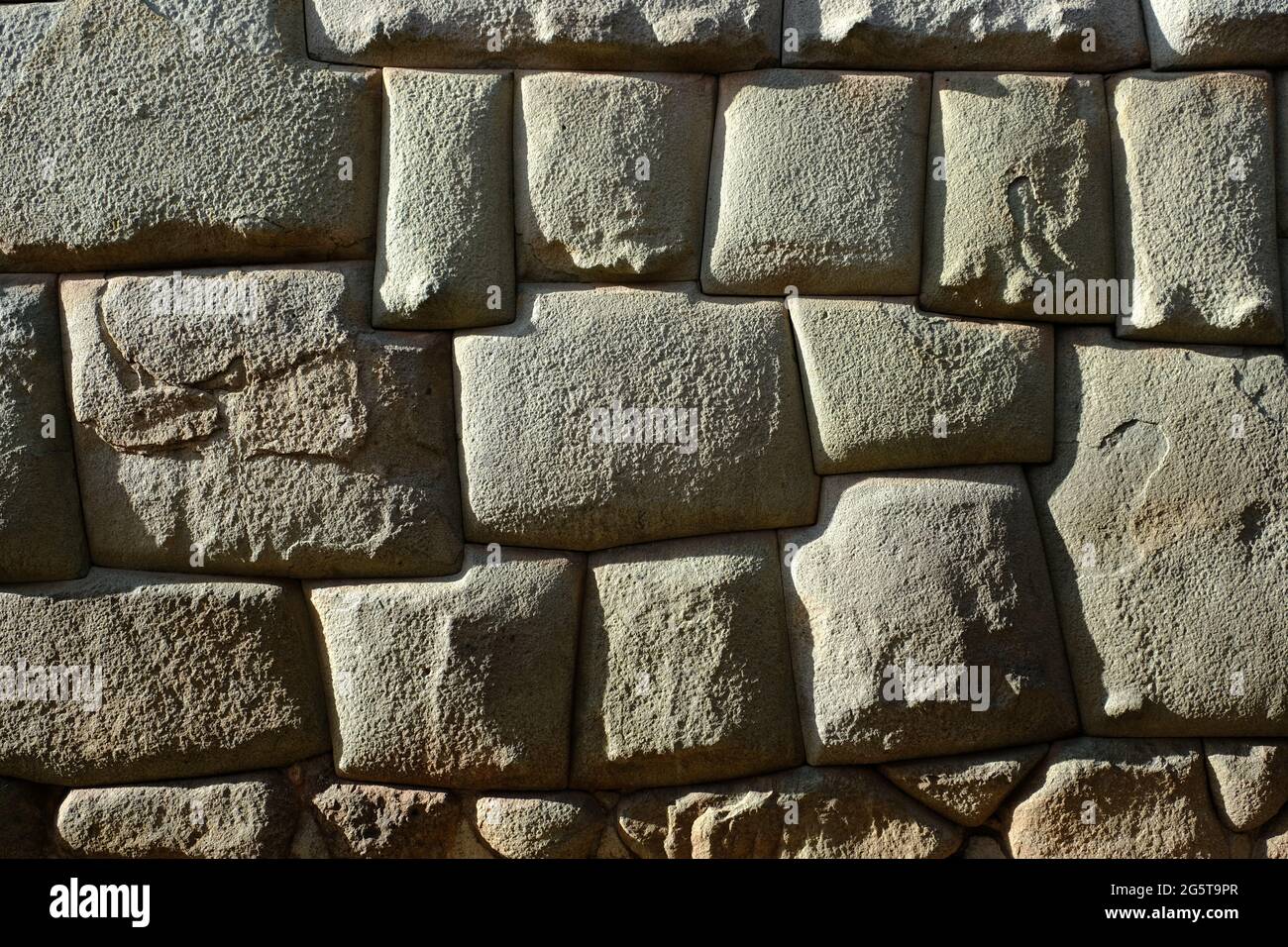

You’re walking down Hatun Rumiyoc street in Cusco, dodging selfie sticks and local vendors, and then you see it. It’s a green diorite block. Honestly, at first glance, it just looks like a very big, very clean rock stuck in a wall. But then you start counting the corners. One, two, three... all the way to twelve. This is the Piedra de los 12 Ángulos, and it’s basically the ultimate "flex" of Inca engineering.

It’s not just a tourist trap. It’s a mathematical miracle.

Cusco is full of these moments where you realize the Spanish tried their hardest to build over the Inca foundations, but they couldn’t quite match the craftsmanship. This stone is part of the wall of the Palace of Hatunrumiyoc, which belonged to Inca Roca. Today, it serves as the foundation for the Archbishop's Palace. It’s a weird metaphor for Peruvian history: colonial weight resting on an indestructible indigenous base.

What makes the Piedra de los 12 Ángulos so special?

Most people think the "twelve angles" are just for show. They aren't. In Inca architecture, every single notch and protrusion served a structural purpose. The Piedra de los 12 Ángulos is a masterpiece of "ashlar" masonry, where stones are shaped to fit together without a single drop of mortar.

Think about that.

No cement. No glue. Just friction and gravity. You literally cannot fit a piece of paper—or even a razor blade—between these stones. It’s tight. If you visit today, you’ll notice a small fence and often a guard dressed in traditional Inca attire nearby. They have to protect it because, for some reason, people really want to touch those seams. Don't do that. The oils from human skin actually degrade the stone over centuries.

✨ Don't miss: Historic Sears Building LA: What Really Happened to This Boyle Heights Icon

The precision here is staggering because diorite is hard. We’re talking about a 6-to-7 on the Mohs scale. The Incas didn't have iron or steel tools. They used harder "cobble" stones—usually hematite or black basalt—to basically beat the diorite into submission. It was a process of constant abrasion and sanding. Imagine spending months, maybe years, just to get one stone to fit into its neighbors like a 3D jigsaw puzzle.

The Earthquake Proof Secret

Cusco sits on a major fault line. It shakes. A lot.

In 1650 and 1950, massive earthquakes leveled the Spanish colonial buildings. The cathedrals crumbled. The houses split open. But the Inca walls? They barely moved. The Piedra de los 12 Ángulos stayed exactly where Inca Roca’s architects put it.

The secret is in the "dance."

When the earth shakes, these stones are designed to vibrate and shift in place. Because they have so many angles—like the twelve on this specific stone—they lock into each other during the tremors. They move, they settle, and then they lock back into their original position. It’s basically high-tech seismic insulation made of rock. The Spanish built rigid walls with mortar, which cracks under pressure. The Inca built flexible, interlocking systems.

🔗 Read more: Why the Nutty Putty Cave Seal is Permanent: What Most People Get Wrong About the John Jones Site

The Myth of the "Thirteenth Angle"

Every tour guide in Cusco has a different story. Some will tell you that the twelve angles represent the twelve months of the year. Others say they represent the twelve royal families (panacas) of Cusco.

The truth? We don't actually know if the number twelve was intentional or just a byproduct of the stones surrounding it. Architecture in the Andes was often organic. If the stone below it had five points, the stone above it had to adapt. It’s a reactive way of building.

There’s also a persistent rumor about a 13-angled stone or even a 14-angled one hidden elsewhere in the city. Some people claim they've found a 13-point stone in the 뒷 alleys of San Blas. While there are stones with many angles throughout the Sacred Valley—Ollantaytambo has some beauties—the Piedra de los 12 Ángulos remains the most famous because of its sheer size and central location. It’s the celebrity of the lithic world.

How to actually see it without the crowds

If you go at 10:00 AM, you’re going to have a bad time. You’ll be fighting through tour groups from three different continents.

- Go at dawn. The light hits the street in a way that highlights the texture of the diorite around 6:30 AM. Plus, the street is empty.

- Go late at night. The street lamps give it a moody, ancient vibe.

- Look at the surrounding stones. Everyone focuses on the big one, but the entire wall is a masterclass. Look at how the stones at the bottom are larger to support the weight (the "megalithic" style) and how they taper as they go up.

The "Perfect Fit" Controversy

Archaeologists like Jean-Pierre Protzen have spent decades trying to figure out exactly how the Incas did this. He actually experimented with stone-tool techniques to prove that you don't need "aliens" or "lasers" to make the Piedra de los 12 Ángulos.

💡 You might also like: Atlantic Puffin Fratercula Arctica: Why These Clown-Faced Birds Are Way Tougher Than They Look

It’s called the "protracted trial and error" method. You shape the stone, you test the fit, you see where it's hitting, you grind that spot down, and you try again. It’s tedious. It’s exhausting. It’s deeply human. To suggest that the Incas couldn't do this themselves is kind of an insult to the incredible labor and mathematical genius they possessed.

They also used "scribing" techniques, similar to how log cabin builders fit uneven logs together. By using a tool to trace the shape of the bottom stone onto the top stone, they could match the contours exactly.

What you need to know before you go

The stone is located on Calle Hatun Rumiyoc, about two blocks from the Plaza de Armas. It’s free to look at. You don't need a ticket.

But remember:

- No touching. Seriously. There are cameras and guards.

- Watch for the "Inca" cosplayers. They are happy to take a photo with you, but they expect a tip (usually 5 to 10 soles).

- The street is narrow. Watch out for the occasional delivery motorcycle that zooms through.

Exploring the rest of the wall

Once you’ve had your fill of the twelve angles, keep walking up the hill toward the San Blas neighborhood. The stonework changes. It gets a bit more "rustic," but it’s still impressive. The transition from the imperial "Seda" style (smooth and rectangular) to the "Cellular" style (polygonal like a honeycomb) tells the story of Cusco’s different construction phases.

The Piedra de los 12 Ángulos isn't just a rock. It’s a testament to a civilization that viewed stone as something living. To the Inca, these stones were "uacas"—sacred objects. When you look at the twelve angles, you aren't just looking at a wall; you're looking at a 500-year-old conversation between a mason and the earth.

Actionable Steps for your visit

- Map it out: Save "Calle Hatun Rumiyoc" on your offline Google Maps.

- Timing: Set an alarm for 6:00 AM. Walking through Cusco when the sun rises over the Andes is a spiritual experience, twelve angles or not.

- Context: Visit the Museo Inka beforehand. It’s just around the corner and gives you the historical context of the Palace of Hatunrumiyoc so you understand why this wall was built there in the first place.

- Photography: Use a wide-angle lens if you have one, but for the stone itself, a standard 35mm or 50mm lens will capture the seams better without distortion.

Don't just take a photo and leave. Stand there for five minutes. Look at the seams. Think about the fact that no mortar is holding that massive weight in place. It’s been standing for over half a millennium, survived multiple invasions, and withstood earthquakes that leveled "modern" buildings. That’s the real power of the stone.