History isn't just a list of dates. It's usually a story about someone getting pushed too far. In May 1902, that "someone" was about 147,000 miners in Eastern Pennsylvania. They walked off the job, extinguished their headlamps, and basically held the entire American economy hostage for months. This wasn't just some local squabble over pennies. It was a brutal, high-stakes standoff that forced a U.S. President to threaten the military takeover of private industry. If you’ve ever wondered why the federal government sticks its nose into labor disputes today, you can trace a direct line back to this specific winter of 1802.

Working in the anthracite mines was a nightmare. Pure and simple. Miners weren't just fighting for more money; they were fighting to not die in a dark hole 500 feet underground. By the time the Pennsylvania coal strike of 1902 kicked off, these guys were dealing with stagnant wages that hadn't moved in years, despite the cost of living skyrocketing. They wanted a 20% raise. They wanted an eight-hour workday. Mostly, they wanted the coal operators to actually acknowledge that the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) existed. The owners? They weren't having it. George Baer, the spokesperson for the mine owners, famously (and arrogantly) claimed that the interests of the laboring man would be protected "not by the labor agitators, but by the Christian men to whom God in His infinite wisdom has given the control of the property interests of the country."

Talk about a PR disaster.

Why the Anthracite Region Was a Powder Keg

Anthracite coal is different. It’s hard, it’s shiny, and back then, it was the primary fuel used to heat homes in major cities like New York and Philadelphia. Unlike bituminous coal, which was found all over the place, anthracite was concentrated in a few counties in Pennsylvania. This gave the miners incredible leverage. If they stopped digging, the East Coast froze.

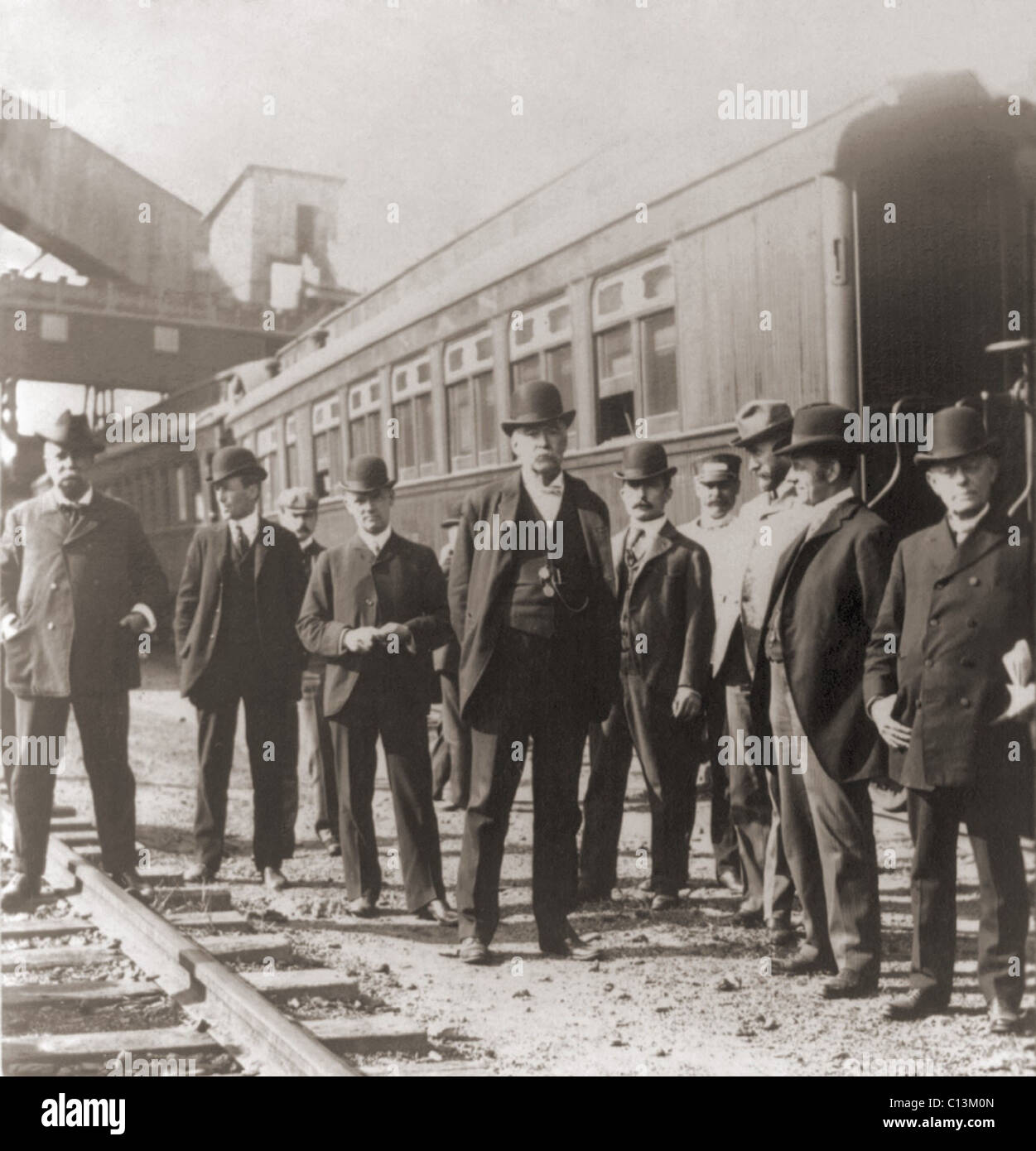

John Mitchell led the charge. He was the president of the UMWA, and honestly, he was a bit of a genius at optics. He knew that for the strike to work, the miners had to stay peaceful. He didn't want the state militia coming in to crack skulls because of a riot. He wanted the public to see the "Christian men" owners as the villains. It worked. For months, the mines stayed silent. The "breakers"—those massive, soot-stained buildings where coal was processed—sat like ghosts against the Appalachian skyline.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Air France Crash Toronto Miracle Still Changes How We Fly

As summer turned to autumn, people started panicking. The price of coal went from $5 a ton to $30. Schools started closing because they couldn't heat the classrooms. The poor were literally breaking up their furniture to burn for warmth. This is where the Pennsylvania coal strike of 1902 stopped being a labor issue and started being a national security crisis.

Enter Teddy Roosevelt: The Man Who Broke the Rules

Presidents didn't usually get involved in strikes. Before 1902, if a President sent troops, it was to help the owners break the strike. Think back to the Pullman Strike or Homestead. The government was the "muscle" for big business.

Theodore Roosevelt changed the game.

He was terrified of a winter coal famine. He saw the social unrest brewing in the cities and realized that if he didn't act, there might be a revolution on his hands. He summoned both the union leaders and the mine owners to the White House in October. This was unheard of. The owners were insulted. They refused to even speak to Mitchell in the same room. They told Roosevelt he should just do his job, send in the army, and force the miners back to work.

🔗 Read more: Robert Hanssen: What Most People Get Wrong About the FBI's Most Damaging Spy

Roosevelt was privately fuming. He later said he wanted to take one of the owners by the "seat of his breeches" and chuck him out the window. Instead, he played a dangerous hand. He leaked word that if a settlement wasn't reached, he would order the U.S. Army to seize the mines and operate them as a government entity. This was a massive stretch of executive power. It might have been unconstitutional, but it worked. J.P. Morgan, the legendary financier who had a massive stake in the railroads that hauled the coal, realized Roosevelt wasn't bluffing. He pressured the owners to accept a commission to settle the dispute.

The "Square Deal" and What the Miners Actually Got

The strike ended on October 23, 1902. The miners went back to work, but the final verdict didn't come until March of the following year when the Anthracite Coal Strike Commission released its report.

- The Win: Miners got a 10% wage increase (half of what they asked for).

- The Compromise: The workday was shortened from ten hours to nine.

- The Loss: The owners still refused to officially recognize the UMWA as a bargaining unit.

- The "Standard": This established the "Square Deal," Roosevelt’s philosophy that the government should act as an impartial referee between capital and labor.

It’s easy to look at the 10% raise and think the miners lost. But they didn't. They proved that a united workforce could stand up to the "robber barons" and win. They proved that the President of the United States had to care about the "forgotten man" in the mines.

Common Misconceptions About 1902

A lot of people think this strike ended child labor in the mines. It didn't. The "breaker boys"—kids as young as eight or nine who sat for hours picking slate out of the coal—were still there long after 1902. It took decades of further agitation and new laws to fix that horror. Another myth is that the strike was totally peaceful. While Mitchell tried his best, there were still clashes with the Coal and Iron Police, a private force hired by the owners that was notoriously brutal.

💡 You might also like: Why the Recent Snowfall Western New York State Emergency Was Different

The Long-Term Impact on Your Life Today

We still live in the shadow of the Pennsylvania coal strike of 1902. It fundamentally shifted how Americans view the role of the federal government. Before this, the "Laissez-faire" approach meant the government stayed out of the way of business. After this, the public expected the President to step in when the economy was at risk.

It also marked the rise of the labor union as a political powerhouse. John Mitchell became a hero. In many mining towns, "Mitchell Day" was celebrated for decades like a religious holiday. The strike showed that the "little guy" had a voice, provided that voice was loud enough to reach the White House.

How to Explore This History Yourself

If you're ever in Northeast Pennsylvania, you can actually feel this history. It’s baked into the landscape. Here is how you can actually connect with the legacy of the 1902 strike:

- Visit the Lackawanna Coal Mine Tour: Located in Scranton, you can go 300 feet underground in an actual anthracite mine. It is cold, damp, and claustrophobic. It gives you immediate empathy for what those 147,000 men were fighting for.

- Check out the Eckley Miners' Village: This is a "patch town" that has been preserved as a museum. You can see the disparity between the modest miners' shacks and the owners' influence.

- Read the Commission Reports: If you’re a real history nerd, the 1903 report of the Anthracite Coal Strike Commission is available in many digital archives. It contains thousands of pages of testimony from miners describing their daily lives.

- Look for the Statues: In Scranton’s Courthouse Square, there is a massive statue of John Mitchell. It’s a reminder that in this part of the world, he was more important than the President.

The 1902 strike wasn't just a labor dispute. It was the moment America decided that the "common good" mattered more than the absolute rights of property owners. It was messy. It was cold. It was tense. But it set the stage for the modern middle class.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Knowledge

To truly grasp the scale of the labor movement that followed this event, research the Ludlow Massacre or the Battle of Blair Mountain. These events show what happened when the government didn't intervene as a neutral party. You can also look into the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, which finally gave miners the official union recognition they were denied in 1902.