It’s hard to overstate how much the Penn State sex scandal fundamentally broke the world of college athletics. Seriously. Before 2011, Jerry Sandusky was a retired defensive coordinator who was basically a living legend in State College. He had this charity, The Second Mile. He was the right-hand man to Joe Paterno, a coach who was more like a deity than a guy on a sideline. Then the grand jury report dropped.

Everything shifted.

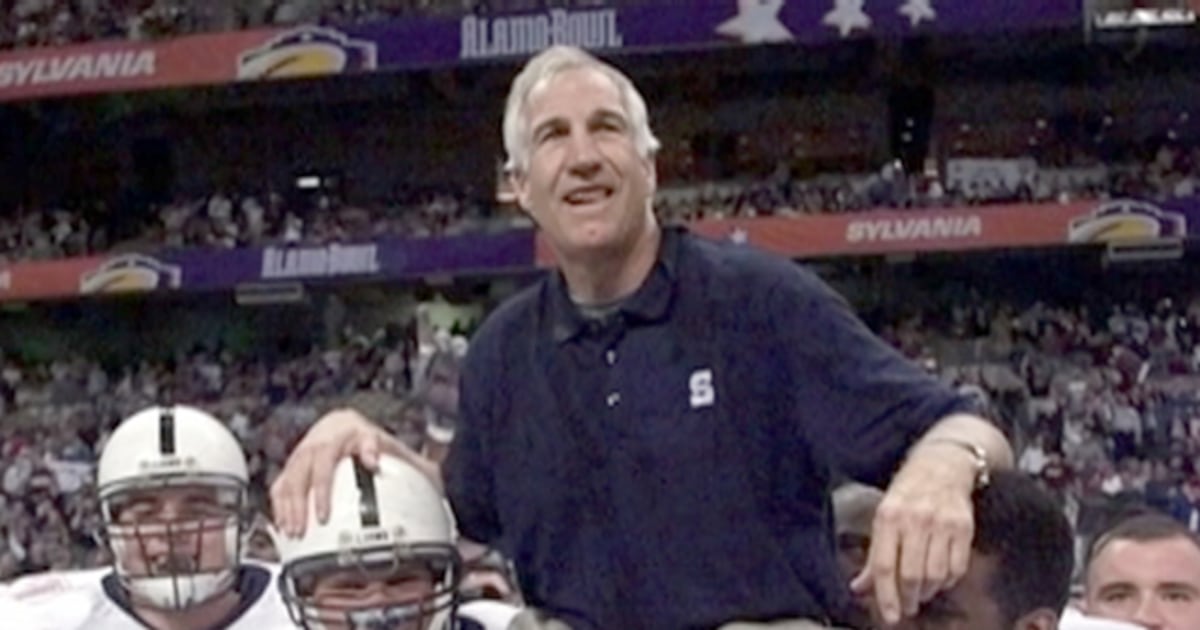

People often forget how fast the dominoes fell once the news broke. On November 5, 2011, the world found out that Sandusky had been charged with decades of horrific sexual abuse involving minors. Within days, the campus was in a state of literal riot. By November 9, Joe Paterno—the man who had more wins than anyone in major college football history—was fired over the phone. Not in person. Not with a gold watch. Just a phone call that ended an era.

Why the Penn State sex scandal still haunts Happy Valley

The reason we’re still talking about this isn't just because of the crimes themselves, which were genuinely stomach-turning. It’s about the cover-up. Or, more accurately, the "failure to act." When people search for details on the Penn State sex scandal, they aren't just looking for crime stats. They’re looking for how a massive institution with thousands of eyes on it could let something like this happen for years.

The 2012 Freeh Report, led by former FBI Director Louis Freeh, was the hammer. It alleged that Paterno, University President Graham Spanier, and other top officials basically prioritized the reputation of the football program over the safety of children. Now, look, there’s been a ton of debate about that report since it came out. Some people think it went too far; others think it didn't go far enough. But the impact was undeniable. The NCAA didn't just slap Penn State on the wrist. They leveled them.

A $60 million fine. A four-year postseason ban. A massive reduction in scholarships. And, most controversially at the time, the vacating of 111 wins from Paterno’s record between 1998 and 2011.

It felt like the "death penalty" without actually being the death penalty.

🔗 Read more: Why Funny Fantasy Football Names Actually Win Leagues

The victims and the human cost

We shouldn't get too bogged down in the football of it all. Honestly, the football is the least important part. The victims—referred to in court documents as Victim 1, Victim 4, and so on—faced lifelong trauma while the system designed to protect them looked the other way.

One of the most harrowing accounts came from Mike McQueary. He was a graduate assistant back in 2001. He walked into the Lasch Football Building showers and saw something he couldn't unsee. He reported it to Paterno. Paterno reported it to his superiors. But it stopped there. No police. No social services. Just a quiet conversation in wood-paneled offices. That 10-year gap between McQueary’s report and Sandusky’s arrest is the darkest part of this whole saga.

Breaking down the legal fallout

The court cases dragged on for years. It wasn't just Sandusky. Graham Spanier, Gary Schultz, and Tim Curley all faced charges related to child endangerment.

- Jerry Sandusky: He was convicted on 45 of 48 counts. He was sentenced to 30 to 60 years in prison. He’s basically going to spend the rest of his life behind bars at SCI Laurel Highlands.

- The Administrators: After years of legal maneuvering, Spanier eventually served a short jail sentence in 2021. It took a decade to get there.

- The Settlement: Penn State has paid out over $250 million to settle claims with victims. That is a staggering amount of money, but it’s just a fraction of the institutional damage.

How the rules changed after the Penn State sex scandal

If there is any "silver lining" (and that’s a tough phrase to use here), it’s that the Penn State sex scandal forced a total rewrite of how universities handle reporting. Before this, "Mandatory Reporting" laws were kinda fuzzy in a lot of states. Not anymore.

Pennsylvania overhauled its Child Protective Services Law. Now, if you work at a university and you suspect something is wrong, you don't just tell your boss. You call the police. You are legally required to act. The "Chain of Command" excuse that people tried to use in the early 2000s doesn't fly in 2026.

The NCAA’s role and the "Restoration"

Something weird happened a few years after the sanctions. In 2015, the NCAA actually restored Paterno's vacated wins. Why? Because of a settlement in a lawsuit brought by Pennsylvania state officials. It was a polarizing move. For some fans, it felt like justice for a coach they believed was unfairly scapegoated. For others, it felt like a slap in the face to the victims.

💡 You might also like: Heisman Trophy Nominees 2024: The Year the System Almost Broke

It showed that even years later, the wounds from the Penn State sex scandal were nowhere near healed. The community was, and still is, split. You have the "JoePa" loyalists who still gather at his grave, and you have those who believe his statue coming down was the only way for the school to move forward.

What we get wrong about the timeline

A lot of people think this all started in 2011. It didn't. Investigation records show that the police were actually looking into Sandusky as far back as 1998. 1998! A mother reported an incident in the Penn State showers, the police investigated, but the local DA at the time didn't bring charges.

Think about that.

If the system had worked in '98, over a dozen other kids might have been spared. This wasn't a failure of one man; it was a systemic collapse of law enforcement, university administration, and charitable oversight.

The Second Mile: A lesson in trust

Sandusky used his charity, The Second Mile, as a scouting ground. It’s a terrifying lesson in how "good guys" in the community can hide in plain sight. He had the keys to the kingdom. He had the trust of parents who were looking for mentors for their sons.

Today, non-profits and youth sports organizations have drastically different vetting processes. Background checks aren't just a formality now; they are exhaustive. If you're volunteering with kids today, you're likely undergoing a process that was directively influenced by the failures found in the Sandusky case.

📖 Related: When Was the MLS Founded? The Chaotic Truth About American Soccer's Rebirth

Lessons learned and the path forward

So, what’s the takeaway from all this mess?

First, institutional ego is a killer. When an organization becomes "too big to fail"—whether it's a tech giant or a blue-blood football program—it starts to protect the brand over the person. Penn State was the ultimate "Success with Honor" brand. They leaned so hard into that image that they couldn't admit there was a monster in the basement.

Second, the culture of silence is real. It takes an incredible amount of courage to speak up when you’re the low man on the totem pole, like Mike McQueary was. We have to build environments where the whistleblowers aren't the ones who lose their careers.

Actionable steps for the present day:

- Verify Reporting Protocols: If you work in any educational or athletic setting, don't assume the "boss" will handle it. Familiarize yourself with your state's specific mandatory reporting laws.

- Due Diligence on Charities: When donating to or volunteering for youth organizations, look for transparency in their board of directors and their safety policies.

- Support Victim Resources: Organizations like RAINN (Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network) provide the infrastructure that victims in the Penn State case didn't have at the time.

- Stay Critical of Power: Whether it's college football or corporate boardrooms, remember that no individual is bigger than the safety of the community.

The Penn State sex scandal wasn't just a sports story. It was a massive, painful wake-up call for how we protect the most vulnerable people in our society. It's a reminder that "honor" isn't found in a win-loss record, but in what people do when they think no one is watching.