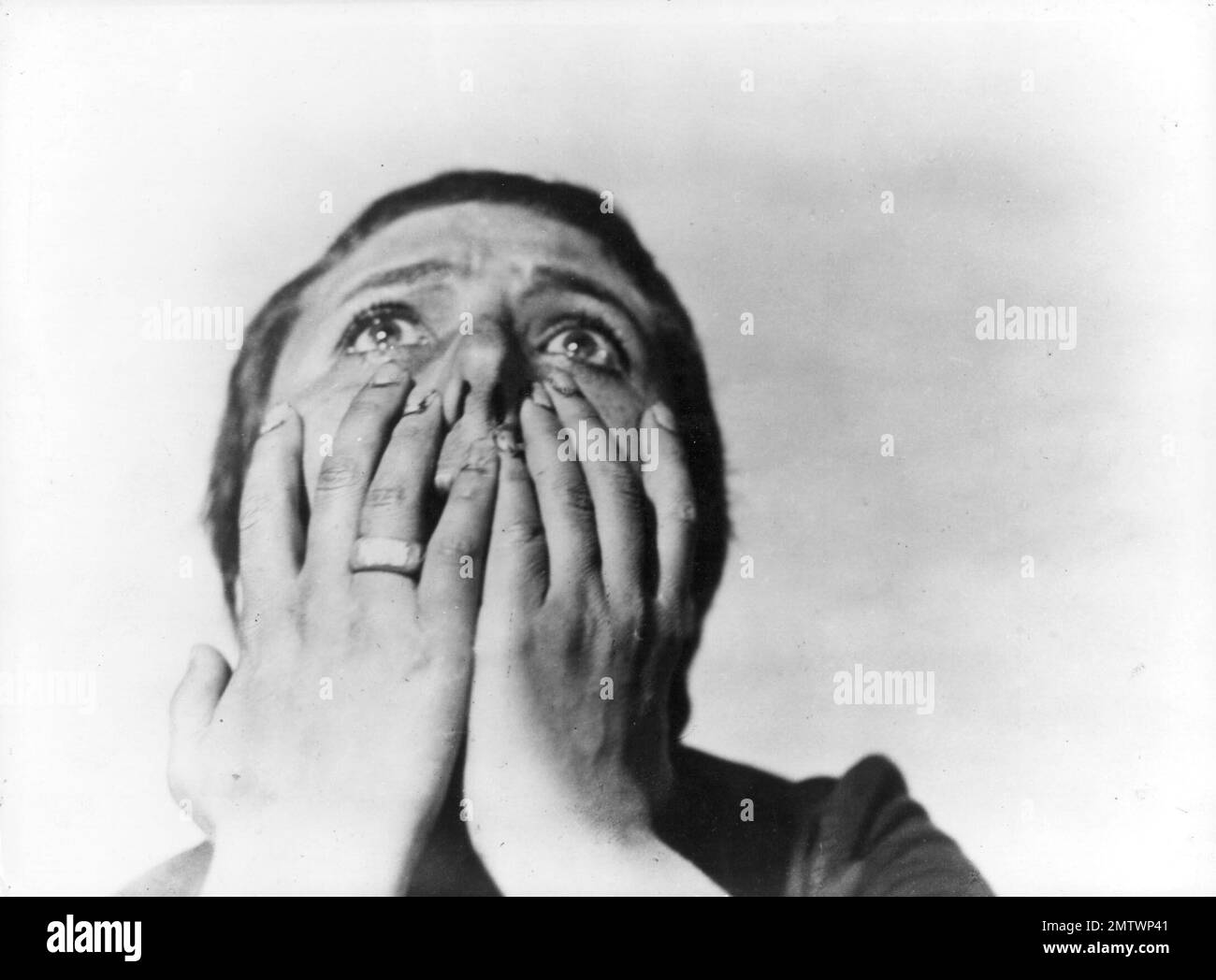

You’ve probably seen the face. Even if you haven’t watched a single second of silent film, you know those eyes. They’re wide, wet with tears, and looking upward toward a heaven that feels both infinitely close and devastatingly far away.

That face belongs to Renée Jeanne Falconetti. In 1928, she gave a performance in The Passion of Jeanne d’Arc that didn’t just change acting—it basically broke the medium of film.

Honestly, calling it a "movie" feels a bit small. It’s more like a visual haunting. Director Carl Theodor Dreyer didn't want to make a standard historical epic with horses and clashing swords. He wanted to film the human soul. And he did it by ignoring almost every rule in the book.

Why The Passion of Jeanne d’Arc Still Terrifies Modern Viewers

Most people expect silent films to be dusty, slow, and full of over-the-top pantomime. Not this one. The Passion of Jeanne d’Arc is violent. Not necessarily in a "blood and guts" way—though the ending is brutal—but in its camera work.

Dreyer and his cinematographer, Rudolph Maté, used close-ups like a weapon. They didn't care about showing you the room. They didn't care about where the chairs were or how many people were in the court. Instead, they shoved the camera right into the actors' faces.

You see every pockmark. Every bead of sweat. Every twitch of a cruel mouth.

It’s uncomfortable. It’s supposed to be. By stripping away the background, Dreyer forces you into the trial. You aren't watching a play from the back row; you’re trapped in a small, white-walled room with a group of powerful men trying to break a nineteen-year-old girl.

🔗 Read more: A Simple Favor Blake Lively: Why Emily Nelson Is Still the Ultimate Screen Mystery

The Mystery of the Lost Prints

For decades, we actually didn't have the "real" movie. It’s one of the weirdest stories in film history.

- The original negative was destroyed in a fire at a Berlin warehouse.

- Dreyer tried to rebuild it using alternative takes, but that version was destroyed in a second fire.

- Censors in France and the Catholic Church hacked the remaining copies to pieces because they hated how the priests looked like villains.

Basically, everyone thought the masterpiece was gone forever. Then, in 1981, a janitor at a mental hospital in Norway found several film canisters in a closet. They were labeled "The Passion of Joan of Arc." It turned out to be a pristine copy of Dreyer’s original, uncensored cut.

It’s kind of poetic, right? A film about a "mad" saint found in a psychiatric ward.

What Really Happened with Falconetti?

There is a dark legend that Dreyer was a monster on set. People say he made Falconetti kneel on stone floors for hours until she was in genuine agony. There are rumors she went insane after the shoot and never acted in a film again.

The truth is a bit more nuanced.

Yes, Dreyer was demanding. He wouldn't let the actors wear makeup. He wanted the raw texture of skin. If a scene called for Joan to have her head shaved, they did it for real, on camera. You can see the genuine shock and grief in Falconetti’s eyes because she’s actually losing her hair in front of a crew of men.

💡 You might also like: The A Wrinkle in Time Cast: Why This Massive Star Power Didn't Save the Movie

But Falconetti wasn't a fragile victim. She was a successful stage actress in Paris before this. While she did move to South America later and died in Argentina, the "insanity" stories are mostly just that—stories. The reason she never did another movie? She probably didn't need to. After you’ve touched the sun, why bother with a flashlight?

Historical Accuracy vs. Artistic Truth

Dreyer based the script on the actual 1431 trial transcripts. He hired a historian, Pierre Champion, to make sure the dialogue was legit.

But he also cheated.

The real trial lasted for months. Dreyer compresses it into a single, grueling day. He also ignores the politics of the Hundred Years' War. He doesn't care about the English vs. the French. He cares about the individual vs. the institution.

This is why The Passion of Jeanne d’Arc feels so modern. It’s about how systems of power—whether religious, political, or social—try to crush someone who doesn't fit the mold.

The Technical Weirdness That Makes It Work

If you watch closely, the spatial logic makes no sense. If a priest is looking right, Joan might also be looking right, even though they’re supposed to be looking at each other.

📖 Related: Cuba Gooding Jr OJ: Why the Performance Everyone Hated Was Actually Genius

In film school, they call this breaking the 180-degree rule. Usually, it’s a mistake. In this movie, it’s a choice. Dreyer wanted you to feel disoriented. He wanted the world to feel like it was tilting.

The sets themselves were massive and expensive—designed by Hermann Warm, the guy who did The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari—but you barely see them. They were painted pink and yellow so they would show up as specific shades of gray on the new panchromatic film they were testing.

It was a colossal waste of money if you’re looking for "epic scale," but it created a stark, minimalist world that feels like a dream. Or a nightmare.

How to Actually Watch It Today

Don't just put it on in the background while you're on your phone. You’ll miss everything.

- Find the Criterion Collection version. It has the 1981 Norwegian find.

- Pick your soundtrack. Since it’s a silent film, there isn't one "correct" score. Richard Einhorn’s Voices of Light is the most famous, and it’s beautiful. But some people prefer watching it in total silence.

- Watch the eyes. Just the eyes.

Actionable Insights for Cinephiles

If you want to understand why this film matters for your own creative work or appreciation:

- Study the "Face as a Landscape": Notice how Dreyer treats a face like a setting. You can learn more from a forehead wrinkle than a CGI explosion.

- Identify Emotional Pacing: Look at how the cuts get faster as Joan gets closer to the stake. It creates physical anxiety in the viewer.

- Question Authority: The film’s most "villainous" characters are the ones who are most sure they are doing God's work. It’s a masterclass in portraying institutional arrogance.

The film ends with fire and a riot. It’s messy. It’s loud, even though it’s silent. You’ll walk away feeling a bit bruised, but that’s the point. It’s a reminder that 100 years ago, filmmakers were already doing things with a camera that we’re still trying to figure out today.

Go watch it. It’s about as "human" as art gets.