Ever stood at a butcher counter and just... stared? Honestly, we’ve all been there. You want a good steak, but the labels look like a foreign language. You see "Chuck" and think "Roast," but then there’s "Flat Iron" hiding inside it. It’s a lot. Understanding the parts of a beef cow isn't just for farmers or industrial meatpackers; it’s basically the secret code to saving a ton of money and actually cooking a decent dinner.

Most people think a cow is just a giant pile of steak. It isn’t.

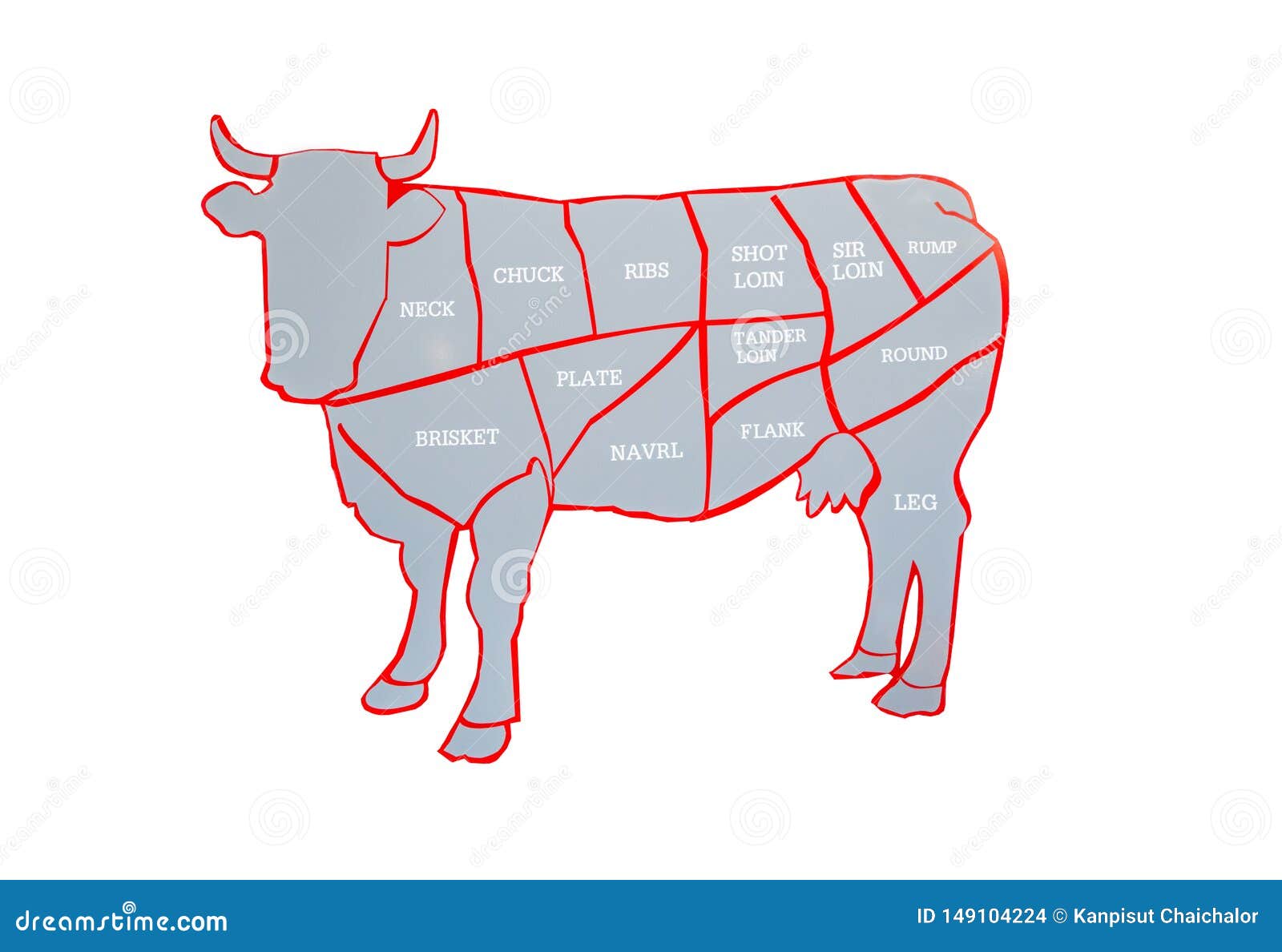

In reality, a beef carcass is divided into what the industry calls "primal cuts." These are the big chunks. Think of them as the zip codes of the cow. From there, you get the sub-primals—the actual steaks and roasts you recognize. But here’s the kicker: the muscle’s job during the cow's life determines exactly how you have to cook it. If you mess that up, you’re chewing on shoe leather.

Why Location Is Everything

Think about a cow’s daily life. They spend all day walking and grazing. The muscles that do the heavy lifting—the legs, the neck, the shoulder—are packed with connective tissue and collagen. These are the "tough" parts. Then you have the back. The back doesn't do much. It just sits there. That’s where the tender stuff lives.

Take the Chuck. This is the shoulder. It supports about 60% of the animal's weight. Because it’s constantly working, it’s lean but riddled with gristle. If you try to grill a thick slab of chuck like a Ribeye, you’re going to have a bad time. But if you braise it? That collagen melts into gelatin. It becomes succulent. On the flip side, the Loin—located right along the spine—is lazy. It’s tender because it never had to work a day in its life.

The Front End: Chuck and Brisket

The Chuck is the largest primal cut. It's basically the neck and shoulder blade area. Most people know it for "Pot Roast," but there’s a hidden gem here: the Flat Iron Steak. For decades, this was just part of a roast until researchers at the University of Nebraska and the University of Florida figured out how to "seam" out the heavy connective tissue. Now, it’s the second most tender muscle in the entire animal.

👉 See also: Finding MAC Cool Toned Lipsticks That Don’t Turn Orange on You

It’s surprisingly affordable.

Then we have the Brisket. This is the breast muscle. It’s incredibly tough. In the past, this was a "trash" cut that nobody wanted because it takes forever to cook. Now, thanks to the Texas BBQ explosion and pitmasters like Aaron Franklin, brisket is liquid gold. It’s two muscles: the "point" (fatty) and the "flat" (lean). You have to cook it low and slow—usually around 225°F—for 12 to 16 hours to break down those fibers.

The Rib: Where the Money Is

Moving back from the shoulder, we hit the Rib. This is where things get fancy. You get the Ribeye, the Prime Rib, and Short Ribs here. The Ribeye is famous for marbling. Marbling is just a fancy word for intramuscular fat. Unlike the "fat cap" on the outside of a steak, marbling melts into the meat while it cooks. It acts as a natural basting agent.

- Ribeye Steak: Sold boneless or "bone-in."

- Tomahawk: Just a Ribeye with a massive, cleaned rib bone attached for aesthetics. You’re basically paying for a handle.

- Back Ribs: What’s left after the ribeye meat is removed. Great for BBQ, but not a lot of meat on them.

The Loin and Flank: The High-Rent District

If the cow had a luxury penthouse, it would be the Short Loin and the Sirloin. This is where the Filet Mignon comes from. The tenderloin is a long, pencil-shaped muscle that sits tucked inside the loin. It does zero work. That’s why you can cut it with a butter knife.

Ever wonder about the difference between a T-Bone and a Porterhouse? It’s all about the Tenderloin. Both steaks are a cross-section of the Short Loin, featuring a T-shaped bone with a Strip steak on one side and a Tenderloin on the other. To be called a Porterhouse, the tenderloin section must be at least 1.25 inches wide. If it’s smaller, it’s just a T-Bone.

✨ Don't miss: Finding Another Word for Calamity: Why Precision Matters When Everything Goes Wrong

Don't Ignore the Bottom

The Flank and Plate are located on the belly. This is where you get Skirt Steak and Flank Steak. Skirt steak is the actual diaphragm muscle. It’s very thin, very grainy, and has a massive beefy flavor. It’s the go-to for authentic fajitas. The trick here? You must slice it against the grain. If you slice with the grain, the long muscle fibers stay intact, and it’s like eating rubber bands.

The Back End: Round and Shank

The Round is the hind leg and rump. It’s lean. Very lean. Because there’s almost no fat, it’s prone to drying out. This is where "London Broil" or "Top Round" comes from. It’s best for deli roast beef where you can slice it paper-thin.

The Shank is the lower leg. It’s arguably the toughest part of the cow because it’s full of tendons. But it contains the marrow bone. When you see Osso Buco on a menu, you’re eating the shank. The bone marrow leaks out during the long braising process, creating a rich, buttery sauce that you just can't get from any other part of the animal.

The "Fifth Quarter": Offal and Variety

We can't talk about the parts of a beef cow without mentioning the stuff most people ignore. In the industry, this is the "Fifth Quarter."

- Tongue (Lengua): High fat, very tender if boiled then peeled.

- Oxtail: Actually from the tail. It's incredibly bony but makes the best stock on the planet.

- Tripe: The stomach lining.

- Liver: Nutrient-dense, though the flavor is polarizing.

The trend of "nose-to-tail" eating, popularized by chefs like Fergus Henderson, has brought these cuts back to high-end menus. It's more sustainable, and frankly, some of these bits have more flavor than a standard sirloin.

🔗 Read more: False eyelashes before and after: Why your DIY sets never look like the professional photos

Stop Buying the Wrong Thing

Buying beef is an investment. If you’re making a stew, don’t buy "stew meat" in those pre-cut packs. Those are often just random scraps of different muscles that cook at different rates. Buy a whole Chuck Roast and cut it up yourself. You’ll get a consistent texture every time.

If you want a steak but can't afford a $30 Ribeye, look for the Picanha (Sirloin Cap) or the Teres Major. The Teres Major is a tiny muscle in the shoulder that is almost as tender as a Filet but costs half as much. Most butchers don't put it in the case because it’s a pain to trim, so you might have to ask for it specifically.

Actionable Tips for Your Next Trip to the Butcher

- Touch the meat (through the plastic): For roasts, you want it to feel firm but not rock hard.

- Look for "Select" vs "Choice" vs "Prime": These are USDA grades based mostly on marbling. Prime is the best, Select is the leanest. Most grocery store meat is Choice.

- Check the grain: Look at the lines in the meat. Always plan to slice perpendicular to those lines.

- Ask for "Dry-Aged": If you want a funkier, more intense beef flavor, look for dry-aged cuts. The moisture evaporates, concentrating the flavor and allowing natural enzymes to tenderize the meat.

Understanding the anatomy of the animal changes how you cook. You stop fighting the meat and start working with it. Braise the tough stuff, sear the tender stuff, and never, ever overcook a Flank steak.

Next time you're at the store, skip the pre-packaged ground beef and look at the Short Ribs. Ask the butcher to grind them for you. It’ll be the best burger you’ve ever had in your life.