Money has a way of disappearing just when you think you’ve finally mastered it. In the mid-1850s, the United States was riding a massive wave of optimism. We were building railroads across the wilderness, telegraph lines were stitching the world together, and the California Gold Rush had injected a steady stream of "real money" into the economy. Everything looked great on paper. Then, it all fell apart. The Panic of 1857 wasn't just another dip in the market; it was the moment the world realized that when New York sneezes, London and Paris catch a cold. It was the first truly global financial crisis, and honestly, the way it started is almost like a bad movie plot.

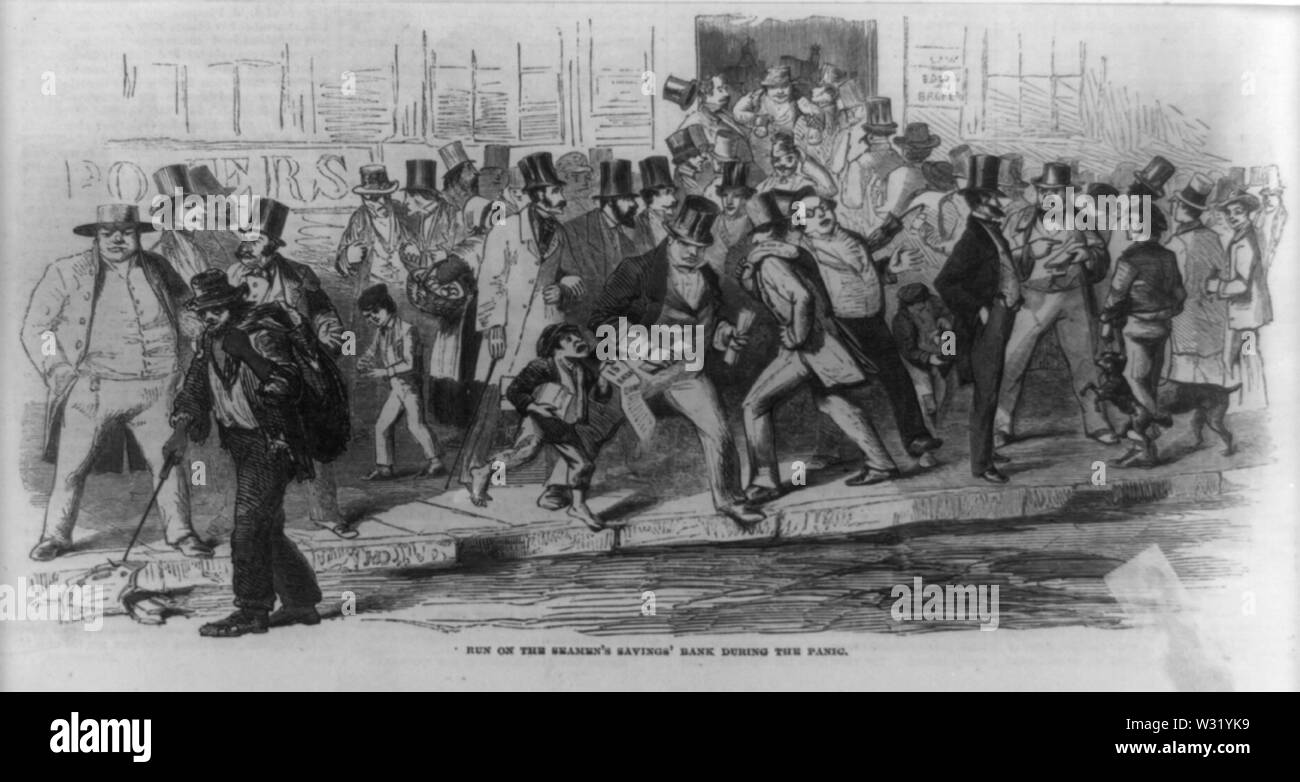

A ship sank. That's basically the spark. The SS Central America, a massive steamer carrying tons of gold from California to New York, went down in a hurricane off the coast of the Carolinas in September 1857. At the time, banks relied on that gold to back up their lending. When the gold didn't arrive, the trust evaporated. People got scared. They ran to the banks to pull their money out, and as we've seen throughout history, when everyone tries to leave the room at once, the door gets stuck.

Why the Panic of 1857 Was More Than Just a Shipwreck

While the sinking of the SS Central America is the dramatic "hook" everyone remembers, the rot was already there. You have to understand that the 1850s was an era of insane speculation. Think of it like the dot-com bubble or the 2008 housing crash, but with steam engines and iron rails. Railroad companies were the tech giants of the 19th century. They were borrowing massive amounts of capital to lay tracks into territories that barely had people living in them yet.

Investors were throwing money at anything with "Railroad" in the name. But by 1857, the market realized that many of these lines weren't going to be profitable for years, if ever. The wheat market also took a massive hit. The Crimean War in Europe had ended, which meant Russian wheat was back on the market. Suddenly, American farmers who had expanded their operations to feed Europe were looking at a surplus and crashing prices.

Then came August 24, 1857. The New York branch of the Ohio Life Insurance and Trust Company failed. This wasn't just some small-town bank; it was a major institution. Its failure sent a shockwave through the financial district. If a "safe" insurance and trust company could go belly up because of bad railroad loans, who was safe? The panic was on. Within weeks, banks in New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore suspended "specie payments." That's a fancy way of saying they refused to give people gold or silver for their paper notes.

The Telegraph: A High-Speed Delivery System for Fear

Before this era, news traveled at the speed of a horse or a sailing ship. If a bank failed in New York, it might take a week for a businessman in New Orleans to find out. But by 1857, the telegraph had changed the game. Information moved instantly. This meant that the panic didn't slowly ripple outward; it exploded.

A merchant in Chicago could see the ticker tape and realize his credit in New York was worthless before his lunch break was over. This speed made the Panic of 1857 unique. It was a "modern" crisis. The interconnectedness of the world, which had been celebrated as a sign of progress, suddenly became a liability. It turns out that when you link everyone's wallets together, one guy's bankruptcy can bankrupt a whole city.

💡 You might also like: Mississippi Taxpayer Access Point: How to Use TAP Without the Headache

The North-South Divide and the Road to Civil War

Historians like James McPherson have pointed out that the Panic of 1857 did more than just break banks; it broke the country. The North was hit incredibly hard. Factories closed, unemployment skyrocketed, and the "bread or death" riots broke out in New York City. People were hungry and angry.

The South, however, stayed relatively stable. Why? Because the world still needed cotton. King Cotton didn't care about New York railroad stocks. Southern plantation owners looked at the chaotic, starving North and felt a dangerous sense of superiority. They believed their economic system—built on the horrific reality of slavery—was more stable and "superior" to Northern industrial capitalism.

This created a massive shift in political leverage. Southerners in Congress used the crisis to push back against Northern demands for tariffs. They argued that the North was a basket case and that the South was carrying the nation's economy. This arrogance fueled the fire that eventually led to secession in 1861. If you want to understand why the Civil War felt inevitable, look at the economic resentment brewed in 1857. The South felt it didn't need the North. They were wrong, obviously, but the 1857 crash gave them the false confidence to try and go it alone.

Real People, Real Losses

It’s easy to talk about "markets" and "railroads," but the human cost was staggering. In New York City alone, an estimated 30,000 to 40,000 people lost their jobs. This was in a city much smaller than it is today. There were no federal unemployment checks. There was no FDIC to insure your bank deposit. If your bank closed its doors, your life savings were simply gone.

I think about the workers in the textile mills in New England. One day they were working ten-hour shifts, and the next, the gates were locked because the owner couldn't get the credit to buy raw cotton. We see diary entries from the time—real accounts from people like George Templeton Strong—describing the eerie silence of the business districts. The bustling energy of Manhattan just... stopped.

The Global Domino Effect

Because the U.S. was such a major exporter of raw materials, the crash didn't stay on our shores. By late 1857, the panic hit Great Britain. The Bank of England had to step in and suspend the Bank Charter Act of 1844. Then it hit France. Then Germany. Then even South America.

📖 Related: 60 Pounds to USD: Why the Rate You See Isn't Always the Rate You Get

This was the first time economists saw a truly "contagious" financial disease. It proved that the 19th-century world was already a globalized economy. You couldn't just isolate one country's failures. The panic lasted about a year and a half in its most acute phase, but the recovery was slow. The U.S. wouldn't truly find its footing again until the massive government spending of the Civil War began.

What We Get Wrong About the Recovery

People often assume that some brilliant government policy fixed the Panic of 1857. Honestly? Not really. President James Buchanan was a big believer in "laissez-faire" (hands-off) economics. He basically told the country to wait it out. He blamed the banks for over-issuing paper money and blamed the people for living too extravagantly.

His solution was to reduce government spending. In hindsight, that's exactly what you don't want to do during a massive contraction, but the economic theories of the time were pretty primitive. The recovery was a slow, painful crawl. It was mostly driven by the sheer resilience of the American spirit and the fact that the fundamental resources—the land, the coal, the iron—were still there. The "bubble" had popped, and the "real" economy had to rebuild from the ground up.

Practical Lessons from 1857 for Today

While the world of 1857 feels like ancient history with its top hats and telegrams, the mechanics of the crash are eerily familiar. Human nature hasn't changed. We still get greedy, we still over-leverage, and we still panic when the "safe" things stop being safe.

If you're looking at your own finances or the current state of the market, here are the takeaways that actually matter:

Liquidity is King. The Panic of 1857 was a "liquidity crisis." People had assets (land, railroad stock), but they didn't have cash. When the bills came due, they couldn't pay. In your own life, having an emergency fund that isn't tied up in the stock market or real estate is the only way to survive a systemic shock.

👉 See also: Manufacturing Companies CFO Challenges: Why the Old Playbook is Failing

Beware of "New Era" Thinking. Every time someone says "this time it's different" because of new technology (whether it's railroads or AI), be skeptical. Technology increases efficiency, but it doesn't eliminate the basic laws of supply and demand. If the "growth" is based on future promises rather than current revenue, it's a bubble.

Interconnectivity is a Double-Edged Sword. We live in a world of instant information. The 1857 telegraph was just the beginning. Today, a tweet can trigger a bank run in minutes. Diversifying where you keep your money—and even what kind of money you hold—is more important now than it was back then.

Understand the Geopolitical Ripple. Economics isn't just about numbers; it's about power. The Panic of 1857 shifted the political balance between the North and South, directly contributing to the Civil War. When the economy shifts today, look at who gains "unearned" confidence. Those are the places where the next political conflict will likely start.

To truly understand our modern financial system, you have to look back at 1857. It was the moment the training wheels came off the global economy. It showed us that we are all connected, for better or worse. The next time you see a market dip or a major bank struggle, remember the SS Central America. Remember that the "real" money is often at the bottom of the ocean, and all we're left with is the trust we have in each other. When that trust breaks, everything else goes with it.

Keep an eye on the debt-to-income ratios of major infrastructure projects today. History shows that when we build too much too fast on borrowed money, the bill eventually comes due. Diversify your holdings across different sectors so you aren't over-exposed to a single "railroad" of our time. Stay informed, but don't let the speed of the news cycle dictate your long-term strategy.