Buffalo, New York. 1901. Imagine walking through a gate and seeing 8,000 electric bulbs glowing at once on a single tower. For people who still used kerosene lamps to read the evening paper, this wasn't just a fair. It was alien technology. The Pan-American Exposition of 1901 was supposed to be the moment the United States declared itself the leader of the Western Hemisphere. It was flashy. It was expensive. And honestly, it turned into one of the most cursed events in American history.

People remember the tragedy—the assassination of President William McKinley—but the "Pan" was so much more than a crime scene. It was a sprawling, 350-acre vision of a future that never quite arrived.

The Electric City That Outshone the Sun

The first thing you’ve gotta understand is the light. Before the Pan-American Exposition of 1901, most people lived in a world of shadows after sunset. Buffalo was the perfect stage because it was right next to Niagara Falls. The organizers tapped into that massive hydraulic power to fuel the "Electric Tower."

Standing 375 feet tall, the tower was covered in creamy, ivory-colored staff—a mix of plaster and hemp fiber—that looked like solid marble but was basically glorified papier-mâché. At night, it turned gold. Then emerald. Then deep crimson. This wasn't just lighting; it was a psychological flex. Thomas Edison himself was there, filming the crowds with his new kinetograph. You can still find that grainy footage in the Library of Congress archives today. It looks like a ghost story, people in top hats and corsets drifting through a neon-lit dreamscape.

The colors were intentional. Architect Carrère and Hastings wanted a "Rainbow City." Unlike the "White City" of the 1893 Chicago World's Fair, Buffalo went bold. They used ochre, blue, and deep reds to represent the different cultures of the Americas. Or at least, what they thought those cultures looked like.

When Everything Went South

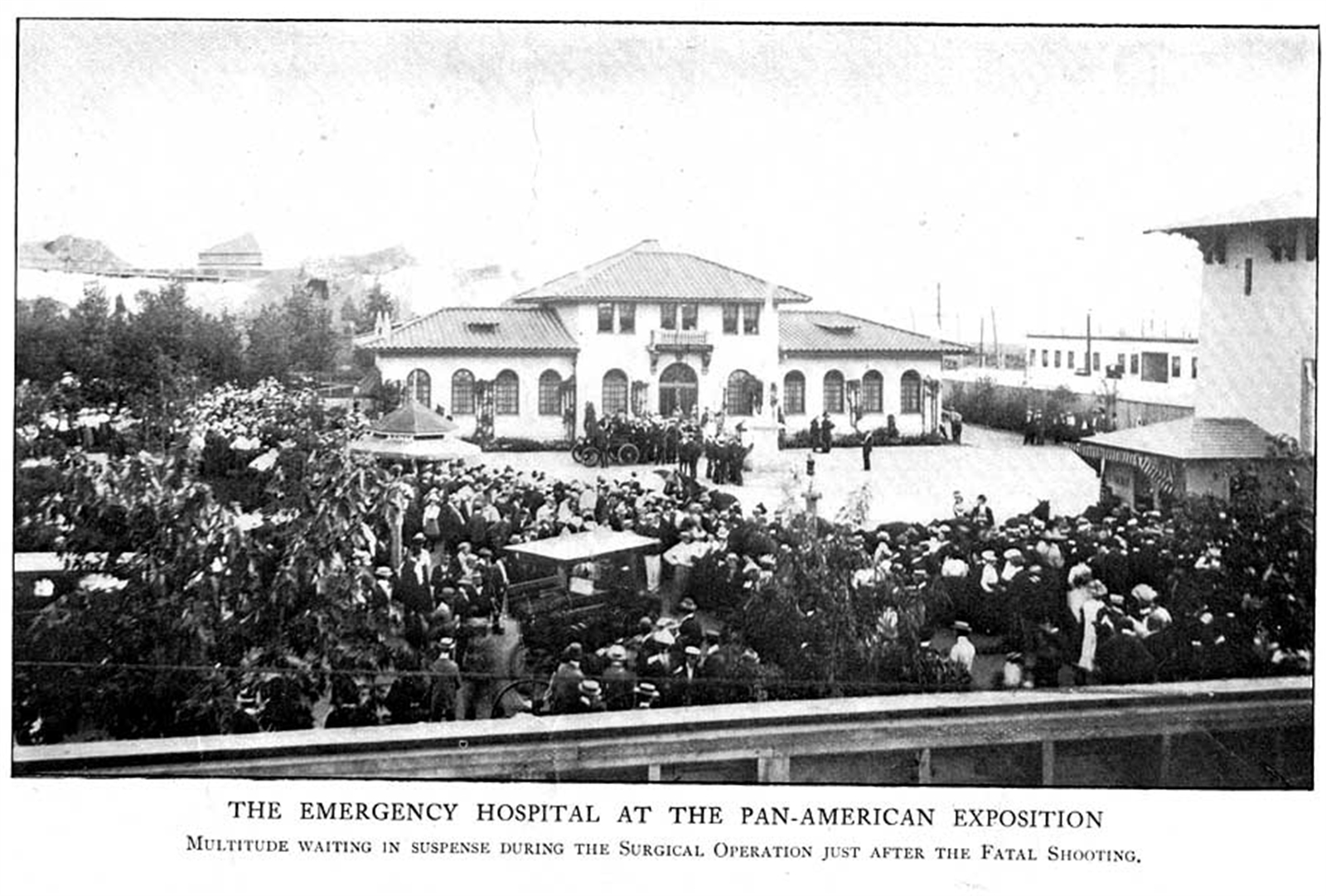

Everything seemed fine until September 6. President McKinley was standing in the Temple of Music, shaking hands. He was a popular guy. He’d just won a second term. Then Leon Czolgosz, an anarchist who’d hidden a .32 caliber Iver Johnson revolver under a handkerchief, stepped up.

✨ Don't miss: Anderson California Explained: Why This Shasta County Hub is More Than a Pit Stop

Two shots.

One bullet bounced off a button. The other tore through the President's stomach.

Here’s the part that really stings: the fair was literally a celebration of modern science, yet science failed the President. They had an X-ray machine on-site—a brand new invention—but the doctors were too scared to use it. They thought the radiation might hurt him. Even weirder? The operating room where they took McKinley didn't have electric lights. They had to use pans to reflect sunlight onto the wound.

He died eight days later of gangrene. The "City of Light" plunged into mourning, and the festive atmosphere evaporated instantly. You can still visit the site today in Buffalo’s Delaware Park area, though the Temple of Music is long gone. A simple stone marker on Fordham Drive marks the spot where the shots rang out. It’s a quiet, residential street now. Kinda eerie if you think about it too long.

The Problematic Side of the Midway

We can't talk about the Pan-American Exposition of 1901 without talking about the "Midway." This was the entertainment strip. It had a massive "Trip to the Moon" ride that used rocking rooms and fans to simulate space travel. People loved it.

🔗 Read more: Flights to Chicago O'Hare: What Most People Get Wrong

But there was a darker side.

The "human zoos" were a staple of these turn-of-the-century fairs. They had an "Old Nuremberg" village, an "African Village," and an "Indian Congress." The organizers brought in hundreds of Indigenous people from across the Americas to live in "authentic" settings while tourists gawked at them. It was deeply exploitative. Geronimo, the famous Apache leader, was actually there. He spent his time signing autographs and selling bows and arrows to tourists. Think about that for a second—one of the most feared warriors in American history turned into a souvenir vendor.

It highlights the massive contradiction of 1901. On one hand, you had the Electric Tower representing the peak of human ingenuity. On the other, you had a society that still viewed other cultures as museum exhibits.

Why the Pan Still Matters to Buffalo

Most of the buildings were never meant to last. They were built out of that "staff" material I mentioned earlier. Once the fair ended in November, they just tore them down or let them rot. It’s a tragedy for architecture fans. Imagine a city of palaces that just... disappears.

However, one building survived. The New York State Building was built out of solid Vermont marble because the organizers wanted it to be a permanent museum. Today, it’s the Buffalo History Museum. If you walk through its halls, you can see the original floor plans and artifacts from the expo.

💡 You might also like: Something is wrong with my world map: Why the Earth looks so weird on paper

What You Can Still See Today

- The Buffalo History Museum: The only surviving major structure.

- The Albright-Knox Art Gallery: Construction started for the fair, though it wasn't finished in time.

- Delaware Park: The general layout of the lake and the bridge still reflects the 1901 landscape.

- Historical Markers: Look for the plaque on Fordham Drive for the McKinley assassination site.

The fair was a financial disaster. It lost over $6 million (in 1901 money!). Between the rainy weather early in the season and the President's death, the crowds just didn't stay. But it put Buffalo on the map as a global city. For a few months, this was the most important place on Earth.

Unraveling the Myths

One common misconception is that the fair was a failure from day one. It wasn't. Before the assassination, it was a tech marvel. The "Aero Cycle" was a massive teeter-totter that lifted cars full of people high into the air. People saw the first "silent" films. They tasted new foods. It was a sensory overload that we can't really comprehend in the age of the internet.

Another myth? That Leon Czolgosz was part of a massive conspiracy. Honestly, he was a loner. He was inspired by the assassination of King Umberto I in Italy, but he acted mostly on his own. The fair's security was actually pretty tight for the time, but they just weren't prepared for a guy with a bandaged hand.

How to Explore this History Yourself

If you’re a history buff or just someone who likes weird, forgotten stories, Buffalo is worth the trip. Don't just go for the wings. Go for the ghosts of 1901.

- Visit the Buffalo History Museum first. They have the most comprehensive collection of Pan-American artifacts, including the gun used by Czolgosz. Seeing the actual weapon is a heavy experience.

- Walk Delaware Park. Use a digital map of the 1901 grounds to overlay where the Electric Tower once stood. It’s crazy to see how a massive lake and palace complex turned back into a public park.

- Check out the Wilcox Mansion. This is where Theodore Roosevelt was inaugurated after McKinley died. It’s a National Historic Site now. It bridges the gap between the tragedy at the fair and the start of the "Progressive Era" in American politics.

- Read "The City of Light" by Lauren Belfer. It’s a novel, sure, but the historical research is impeccable. It captures the tension between the wealthy elite and the workers who actually built the "Rainbow City."

The Pan-American Exposition of 1901 serves as a time capsule. It caught the world at a turning point—moving from the Victorian era into the frantic, electric, and often violent 20th century. It showed us that no matter how bright we light up the night, we can't always see what's coming around the corner.