Look at your thumb. Now imagine everything you’ve ever known—every high school crush, every tax return, every war, and every single person you’ve ever seen on the news—is sitting on a speck of dust about a tenth of the size of that thumbnail. That is basically what happened on February 14, 1990. NASA’s Voyager 1 was about 3.7 billion miles away, screaming toward the edge of the solar system at roughly 40,000 miles per hour, when it turned its camera around one last time. The result was the image of earth from voyager, a photo that shouldn’t have worked and almost didn’t happen.

It’s grainy. It’s blurry. Honestly, if you didn’t know what you were looking at, you’d probably think it was a smudge on your screen or some sensor noise from a cheap 90s camcorder. But that tiny pixel, caught in a scattered beam of sunlight, changed how we think about our place in the universe.

The fight to get the shot

Most people think NASA just decided to take a "selfie" on a whim. That’s not even close to the truth. Carl Sagan, who was part of the imaging team, had been pushing for this photo since the late 70s. He knew the image of earth from voyager would be a philosophical gut-punch. But the engineers? They were terrified.

Pointing a sensitive camera back toward the Sun—even from four billion miles away—is like staring at a laser with your naked eye. There was a very real risk of frying the Vidicon cameras. Plus, Voyager was old. It was running on technology that makes a modern calculator look like a supercomputer. NASA leadership argued that there wasn’t any real "science" to be gained from looking back. It was a vanity project in their eyes. Sagan had to go all the way to the top, eventually getting NASA Administrator Richard Truly to sign off on the command.

Even then, it wasn't a quick "point and click" situation. The spacecraft had to execute a complex series of 60 separate exposures. Earth was just one part of a "Family Portrait" of the solar system. Because Earth is so close to the Sun from that distance, it was incredibly difficult to capture without the Sun’s glare washing everything out.

Why it looks the way it does

If you look closely at the original image of earth from voyager, you’ll notice these weird diagonal bands of light. Those aren't "beams" from heaven or alien tractor beams. They are internal reflections. Because the camera was pointed so close to the Sun, light bounced around inside the camera optics, creating those streaks. By sheer cosmic luck, Earth just happened to be sitting right in the middle of one of those rays.

🔗 Read more: Calculating Age From DOB: Why Your Math Is Probably Wrong

It makes the photo look more cinematic than it actually is.

The Earth itself is less than a single pixel (0.12 pixel, to be exact) in size. It’s a pale blue dot. Voyager 1 was so far away—beyond the orbit of Neptune—that the Earth didn't show any features. No clouds. No continents. No blue oceans. Just a faint, bluish point of light. It’s a sobering reminder that from the perspective of the cosmos, we are practically invisible.

The technical nightmare of 1990 data

We take high-speed internet for granted now. Back then? Voyager had to beam that data back across billions of miles using an 8-bit signal. It took months for the full sequence of photos to reach Earth. When the scientists finally processed the digital files, they had to hunt through the noise to even find the Earth.

Sagan’s legacy and the "Pale Blue Dot" speech

You can't talk about the image of earth from voyager without mentioning Sagan’s 1994 speech. It’s become the definitive text of the space age. He pointed out that every king and peasant, every "young couple in love," and every "corrupt politician" lived out their lives on that "mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam."

It was a call for environmentalism and human kindness.

💡 You might also like: Installing a Push Button Start Kit: What You Need to Know Before Tearing Your Dash Apart

If we look at that photo and still think we’re the center of the universe, we’re missing the point. The photo highlights our "imagined self-importance," as Sagan put it. In 2020, for the 30th anniversary, NASA JPL engineer Kevin Gill reprocessed the original data using modern image-processing techniques. He cleaned up the noise and adjusted the color balance, making the dot pop just a bit more. It didn't change the content, but it made the isolation feel even more profound.

The "Family Portrait" context

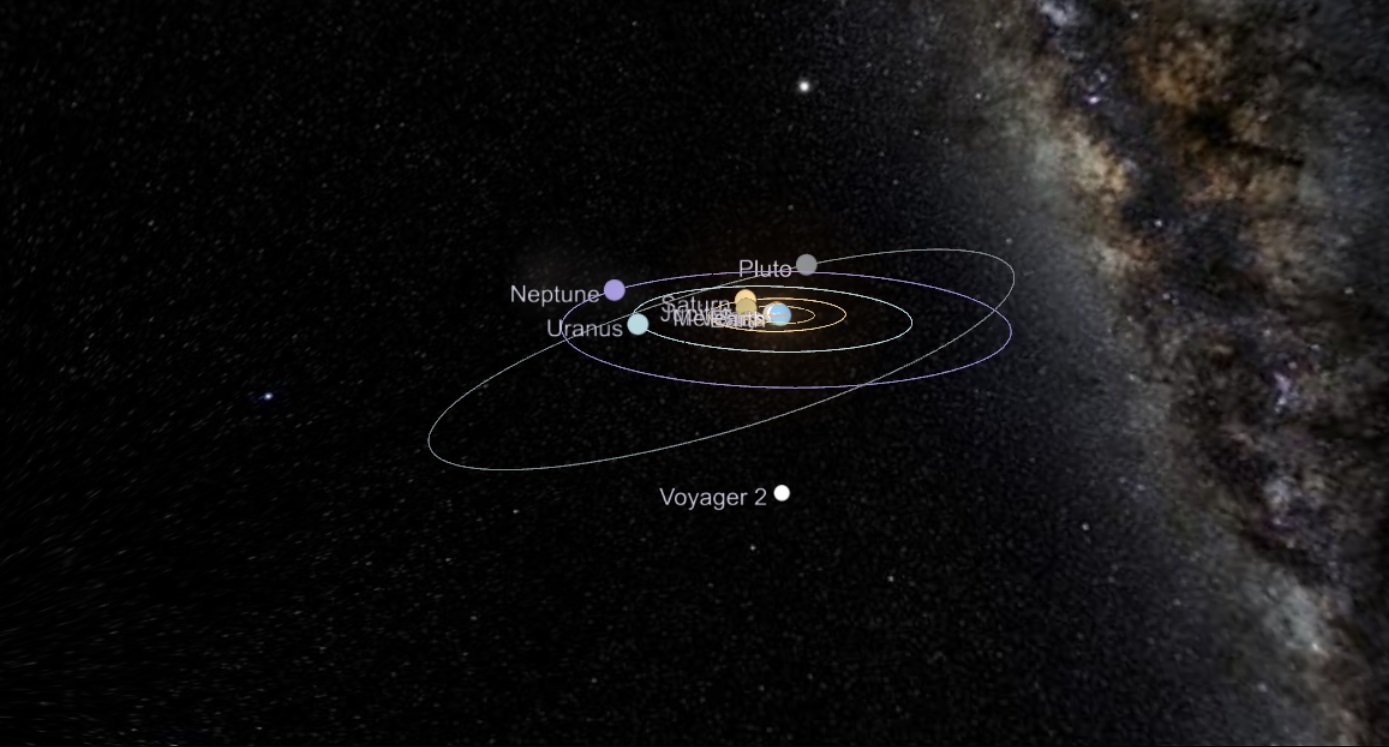

While the Pale Blue Dot gets all the glory, it was actually part of a larger mosaic. Voyager 1 took photos of Neptune, Saturn, Jupiter, Venus, and Uranus too. It tried to catch Mars and Mercury, but Mercury was lost in the Sun's glare and Mars was obscured by the scattered light in the camera.

This was the last time Voyager 1’s cameras were ever turned on.

After the sequence was completed, NASA sent the command to shut down the imaging system forever. Why? To save power and memory for the instruments that actually mattered for the interstellar mission—things like the Magnetometer and the Cosmic Ray Subsystem. The cameras are still there, sitting cold and dark, as the spacecraft drifts further into the Great Unknown.

What most people get wrong about the photo

A common misconception is that this is the "Blue Marble" photo. It’s not. The Blue Marble was taken by Apollo 17 astronauts in 1972 from a much closer distance. In that one, you can see Africa and the Antarctic ice cap.

📖 Related: Maya How to Mirror: What Most People Get Wrong

The image of earth from voyager is different because it’s about scale, not detail.

Another weird myth is that you can see the moon in the Pale Blue Dot photo. You can’t. While Voyager did take photos where Earth and the Moon were both visible earlier in its mission (specifically in 1977), by the time it reached 3.7 billion miles away, the Moon was too faint and too close to the Earth to be distinguished as a separate object in that specific frame.

Is it still relevant in 2026?

Actually, it’s more relevant than ever. With the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) showing us galaxies from the beginning of time, and the Artemis missions preparing to put boots back on the Moon, we are seeing more of space than ever. But seeing "more" often makes us feel bigger. Voyager’s photo does the opposite. It reminds us that for all our technological

might, we are still tied to this one tiny, fragile rock.

We haven't found another "dot" yet that can support us.

Actionable insights: How to experience the perspective

If you find the image of earth from voyager as moving as most space enthusiasts do, there are a few ways to really "get" the scale without needing a billion-dollar probe:

- View the 2020 Remaster: Don’t just look at the grainy 1990 version. Look for the Kevin Gill remaster on NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) website. The clarity of the sunbeam makes the isolation of Earth feel much more visceral.

- Use a Scale Model: If you want to understand the distance, take a peppercorn (representing Earth) and walk 300 yards away. Look back. That is roughly the perspective Voyager had.

- Track Voyager 1 in Real-Time: NASA has a "Eyes on the Solar System" web tool. You can see exactly how far Voyager 1 is from Earth right now. As of 2026, it’s over 15 billion miles away—far beyond where it was when it took the famous photo.

- Read "Pale Blue Dot" by Carl Sagan: The book goes far deeper than the quote. It explores the future of human spaceflight and why that tiny image remains the ultimate argument against human tribalism.

The image of earth from voyager wasn't just a photo. It was a mirror. It showed us that in the vastness of the cosmos, the only thing that protects us from the vacuum is our own ability to get along and take care of the only home we’ve ever known.