You’ve probably seen the neon. You might have even stood in the circle of wood at the Opry House near the mall. But if you want to understand the original Grand Ole Opry, you have to stop thinking about a fancy concert hall and start thinking about a life insurance building. It sounds weird. It is weird.

In 1925, Nashville wasn’t "Music City." It was a quiet, southern banking town. Then George D. Hay showed up. He was a former newspaper reporter who called himself the "Solemn Old Judge," and he had this crazy idea for a radio show on WSM (which stood for "We Shield Millions," the slogan of the National Life and Accident Insurance Company). He brought in an 77-year-old fiddle player named Uncle Jimmy Thompson, and they just... played. For an hour. People went nuts.

That was the spark. It wasn’t a polished production. It was loud, chaotic, and felt like a barn dance because, well, that’s exactly what it was.

The original Grand Ole Opry wasn't even called that at first

Back in the early days, it was just the "WSM Barn Dance." The name change was a total accident. In 1927, George Hay was following a broadcast of classical music from the NBC network. He famously quipped, "For the past hour, we have been listening to music taken largely from Grand Opera, but from now on we will present 'The Grand Ole Opry'."

The name stuck. It was a jab at the high-brow culture of the time. It told the working class that their "hillbilly" music was just as valid as anything coming out of a symphony hall in New York.

This wasn't just about songs. It was about identity. If you were a farmer in 1930s Tennessee, the original Grand Ole Opry was your connection to the world. You’d gather the family around the battery-powered radio—the big wooden kind that looked like a piece of furniture—and wait for the signal to drift in through the static.

Why the venue kept changing (It was too popular)

People think the Ryman Auditorium was the first home. It wasn't. The show moved like a nomad because it kept outgrowing its skin.

📖 Related: Isaiah Washington Movies and Shows: Why the Star Still Matters

First, it was a tiny studio at the National Life building. Then, they built "Studio C," an auditorium that could hold 500 people. It wasn't enough. Fans were literally banging on the doors. So they moved to the Hillsboro Theatre in 1934. Then the Dixie Tabernacle in 1936, which was basically a dirt-floor shed with rustic benches. Then the Ridely Broadway-South Nashville Theater.

Each move was a sign of a growing cultural monster.

Finally, in 1943, they landed at the Ryman. That’s the "Mother Church." But remember, the Ryman was originally the Union Gospel Tabernacle. It was built for fire-and-brimstone preaching, not steel guitars. The acoustics were incredible because the room was designed to carry a human voice to the back row without a microphone. When you hear old recordings of the original Grand Ole Opry stars like Roy Acuff or Minnie Pearl, you’re hearing that room’s natural reverb. It’s haunting.

The "Hillbilly" vs. "Country" Conflict

There’s a misconception that the Opry was always this proud bastion of country music. Honestly, the management was kind of embarrassed by it early on. The insurance executives at National Life wanted to be seen as prestigious. They didn't necessarily want their brand associated with "fiddlin' tunes" and "jug bands."

But the numbers didn't lie. The show sold insurance. It sold flour (Martha White). It sold Goo Goo Clusters.

George Hay was a genius at branding, though. He made the performers dress up in overalls and straw hats, even if they usually wore suits in real life. He wanted that "authentic" rural look. DeFord Bailey, the show's first African American star and a harmonica wizard, was a massive part of this era. He was a pioneer who often had to deal with the harsh realities of Jim Crow while being the most popular act on the air. That’s a layer of the original Grand Ole Opry history that doesn't get enough daylight in the glossy brochures.

👉 See also: Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett: Why Fans Are Still Divided Over the Daimyo of Tatooine

DeFord Bailey and the Pan-American Blues

If you haven't listened to "Pan-American Blues," go find it on YouTube right now. It's just a guy and a harmonica. But he makes that tiny instrument sound like a literal steam engine. DeFord Bailey was the first person to ever record in Nashville. Think about that. The entire Nashville recording industry started because of a Black harmonica player on the Opry.

His exit from the show in 1941 is a point of contention among historians. Some say it was a licensing dispute with BMI/ASCAP. Others point to the underlying racism of the era. Regardless, the original Grand Ole Opry wouldn't have survived its infancy without his talent. He provided the rhythm that defined the show's early sound.

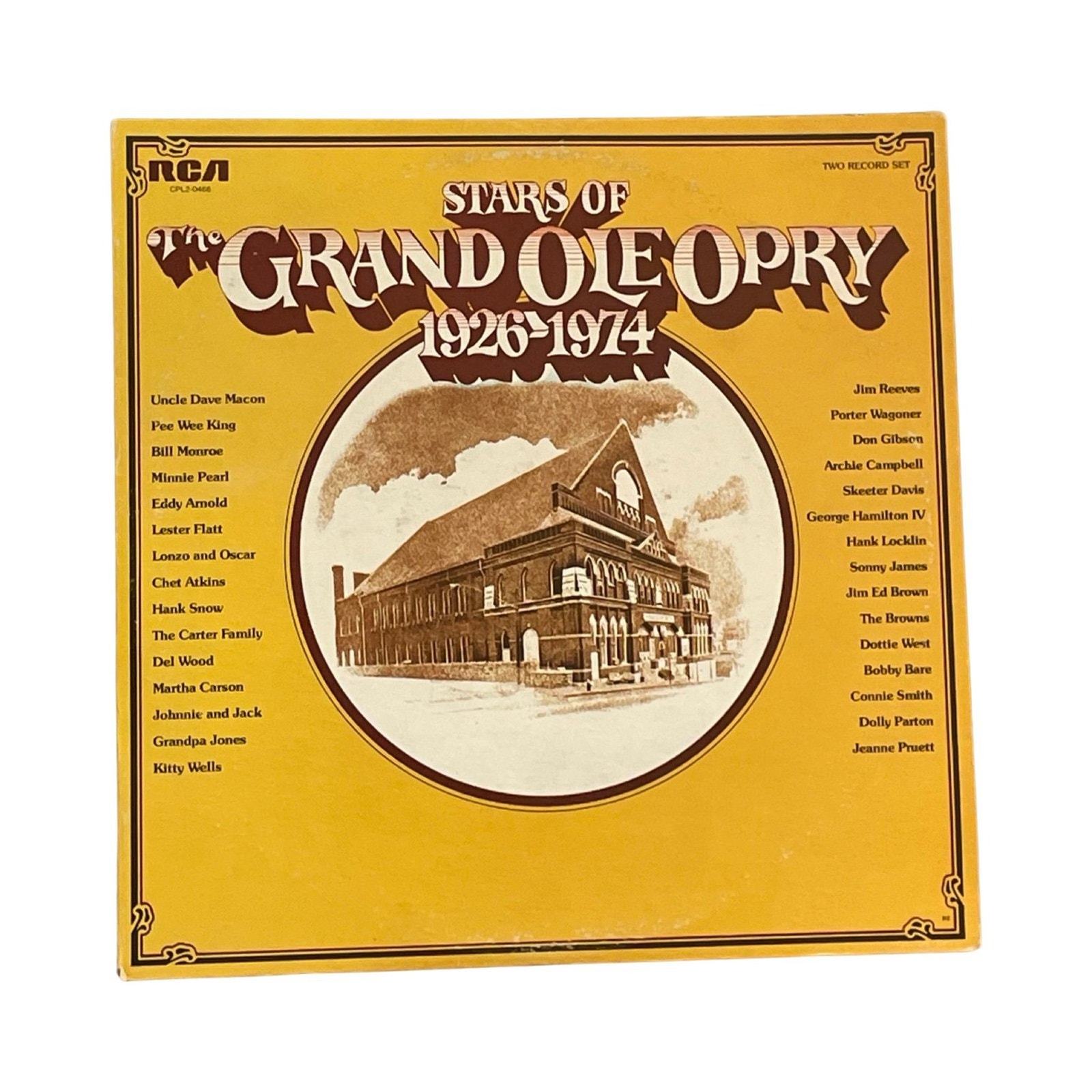

The Ryman Years: 1943 to 1974

This is the era most people romanticize. It was hot. There was no air conditioning. The performers would hang out at Tootsie’s Orchid Lounge across the alley because the Ryman didn't have dressing rooms. They’d run across the alley, grab a drink, and then sprint back through the "stage door" to perform for millions of listeners.

It was raw.

Hank Williams debuted here in 1949 and got six encores for "Lovesick Blues." They had to tell him to stop so the show could continue. But the Opry was also strict. They fired Hank in 1952 because of his drinking and unreliability. They had rules. You had to show up. You had to respect the "family" atmosphere, even if the music was about heartache and cheating.

What actually makes the "Original" sound?

It wasn't just the instruments. It was the "clear channel" signal. WSM was a 50,000-watt station. On a clear night, you could hear the original Grand Ole Opry in Canada. You could hear it in Mexico.

✨ Don't miss: Why Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy Actors Still Define the Modern Spy Thriller

This created a unified culture. A kid in Kansas was hearing the same song as a mechanic in Alabama. This is how "Country and Western" became a national genre instead of just a regional curiosity.

- The Fiddle: The backbone. It had to be loud enough to cut through the static.

- The Banjo: Uncle Dave Macon brought the showmanship. He’d twirl the banjo, kick his feet, and holler.

- The Comedy: It wasn't just music. Rod Brasfield and Minnie Pearl provided "rural" humor that made the show feel like a variety act.

- The Commercials: "Martha White, the finest flour you can buy!" The jingles were as famous as the songs.

The Move to Opryland: Why some fans never forgave it

In 1974, the show moved to the suburbs. They built a massive theme park and a custom-built theater. To bridge the gap, they cut a six-foot circle out of the Ryman’s stage floor and inlaid it into the new stage.

Is it the same? Technically, yes. The show has never missed a broadcast. Through floods, through the move, through everything. But the original Grand Ole Opry—the one that smelled like floor wax and old wood and sweat—that lives at 5th and Broadway.

When people visit Nashville today, they often skip the museum tours and just go to the new house. That’s a mistake. You can’t understand why Dolly Parton or Garth Brooks care so much about that stage unless you see where the show fought to survive during the Depression.

Actionable Steps for the True History Buff

If you really want to experience the spirit of the original Grand Ole Opry, don't just buy a ticket to a random Saturday night show.

- Visit the Ryman on a Tuesday morning. Stand in the balcony (the "Confederate Gallery"). Feel how the floorboards creak. That’s the sound of the 1940s.

- Listen to the 650 AM WSM signal at night. If you’re within a few hundred miles of Tennessee, try to catch the signal on an actual AM radio. The crackle and pop make the music sound like it did in 1925.

- Research the "Session A" players. Look up the musicians who weren't the "stars" but played on every broadcast. Men like Grady Martin and Hargus "Pig" Robbins. They are the ones who actually built the "Nashville Sound."

- Check the DeFord Bailey Tribute. Visit his exhibit at the Country Music Hall of Fame. It’s a necessary correction to the often whitewashed version of country history.

The Opry isn't just a show. It's a survivor. It outlasted Vaudeville, it outlasted the death of AM radio, and it outlasted the rise of television. It stayed because it was built on something real: the need for people to hear their own lives reflected in a song.

Stop by the Ernest Tubb Record Shop while you’re downtown. It’s right near the Ryman. They used to do the "Midnite Frolic" there right after the Opry ended. It’s one of the few places left that still feels like 1947. Grab a vinyl, talk to the guy behind the counter, and realize that Nashville isn't just a party town. It’s a city built on a radio signal.