If you close your eyes and think of Les Misérables, you probably hear Colm Wilkinson’s soaring falsetto or see Patti LuPone’s desperate, tear-streaked face. It’s weird to think there was a time when these songs weren't icons. Before the billion-dollar movie and the endless school productions, there was just a weird French concept album that almost didn't make it to London. The original cast for Les Miserables wasn't just a group of actors; they were essentially the lab rats for a massive theatrical experiment that changed how we watch musicals forever.

Cameron Mackintosh basically gambled his entire reputation on this.

When the show moved from the Palais des Sports in Paris to the Barbican Centre in London in 1985, the stakes were stupidly high. The critics actually hated it at first. Can you imagine? They called it "Victorian Melodrama." They thought it was too long. But the audience didn't care. They saw something in that first lineup that the "experts" missed.

The Man Who Was Valjean

Colm Wilkinson didn't just play Jean Valjean; he was Valjean. It’s honestly hard to find another actor who has owned a role so completely from day one. Trevor Nunn and John Caird, the directors, knew they needed someone who could sound like a rough convict but also hit those impossible high notes in "Bring Him Home."

Wilkinson had this gravelly, rock-influenced texture to his voice. It wasn't "pretty" in the traditional Broadway sense. It was raw. When he sang the "Soliloquy," he wasn't just performing; he was breaking down. He set a template that every Valjean since has had to follow, for better or worse. Most modern actors still try to mimic that specific "Wilkinson warble," though few can actually pull it off without sounding like they’re having a medical emergency.

He was so essential that Mackintosh insisted he move with the show to Broadway in 1987. Without Colm, the show might have just been another forgotten West End import. He brought a sense of holiness to a character that could have easily been a boring archetype.

The Power of Patti and the London Core

Then there's Patti LuPone.

Before she was a Broadway legend who stops shows to yell at people for using their phones, she was the first English-language Fantine. Her "I Dreamed a Dream" is arguably the definitive version because it isn't a ballad. It’s an angry, jagged protest. LuPone has talked openly about how miserable (pun intended) she was during the London run, mostly because she was lonely and the show was exhausting. But that exhaustion translated into a Fantine that felt genuinely on the brink of death.

🔗 Read more: Emmys 2025 Nominees List: What Most People Get Wrong

She didn't stick around for the Broadway transfer, which is why Randy Graff took over the role in New York. But that 1985 London recording? That's all Patti.

The Supporting Players Who Stole the Show

- Roger Allam as Javert: People forget that the original Javert wasn't a booming baritone in the style of Norm Lewis. Allam played him with a cold, intellectual precision. He wasn't a villain; he was a bureaucrat with a soul made of stone.

- Frances Ruffelle as Eponine: She won a Tony for the role later, and for good reason. She had this "waif" energy that felt very 80s but also perfectly 1832. Her voice had a nasal, contemporary edge that cut through the orchestral swell.

- Michael Ball as Marius: He was basically a kid back then. This role launched his career. He brought a "boy next door" charm to a character who is, let’s be honest, kind of a dimbulb for not noticing Eponine is in love with him.

- Alun Armstrong and Susan Jane Tanner: They were the Thénardiers. They brought a vaudevillian grossness to the show that kept it from becoming too self-serious.

Why the 1985 Lineup is Controversial (Sorta)

There’s always a debate among theater nerds. Is the 1985 London cast better than the 1987 Broadway cast? Or does the 10th Anniversary "Dream Cast" at the Royal Albert Hall take the crown?

Honestly, it depends on what you value. The London cast has a certain "grime" to it. It sounds like a show that is still being figured out. By the time it hit Broadway, things were polished. The tempos were faster. The "Broadway sheen" had been applied. If you want the raw, revolutionary spirit, you go to the original London recording.

The original cast for Les Miserables also included names you might not expect. Look closely at the ensemble of the early days and you'll find people like Anthony Crivello or David Burt, who would go on to have massive careers. The ensemble in this show is notoriously difficult because everyone has to be a powerhouse soloist. There are no "background" singers in the barricade.

The Broadway Shift and the "Dream Cast" Myth

When the show jumped the pond to the Broadway Theatre in March 1987, some things changed. Colm Wilkinson and Frances Ruffelle stayed, but we got new faces like Terrence Mann as Javert.

Mann’s Javert was a different beast entirely—more aggressive, more physically imposing than Allam. This version of the original cast for Les Miserables (the Broadway version) is often what American fans think of as the "real" one. It's the one that swept the Tonys. It’s the one that made Les Mis a household name in the States.

But then 1995 happened.

The 10th Anniversary Concert basically cherry-picked the best people from all the various casts. You had Colm (obviously), Philip Quast as Javert (who many consider the GOAT), and Lea Salonga as Eponine. Because that concert was filmed and blasted onto PBS every three months for a decade, people often mistake it for the "original" cast. It’s not. It’s a "Best Of" compilation.

The Reality of the Revolution

Working in that first cast was a nightmare of logistics. The revolve—the rotating stage—was famous for breaking down. Actors were constantly getting injured. The costumes were heavy, the stage was covered in literal dirt, and the rehearsals were grueling because the script was being rewritten on the fly.

Herbert Kretzmer, who wrote the English lyrics, was often changing lines right before the actors went on. Imagine trying to memorize "One Day More" while the guy who wrote it is still scribbling on a napkin in the wings.

That’s the magic of it, though. That's why the original cast for Les Miserables feels so alive on those old tapes. They weren't performing a "classic." They were trying to survive a three-hour epic that everyone told them was going to fail.

Getting the Full Story Yourself

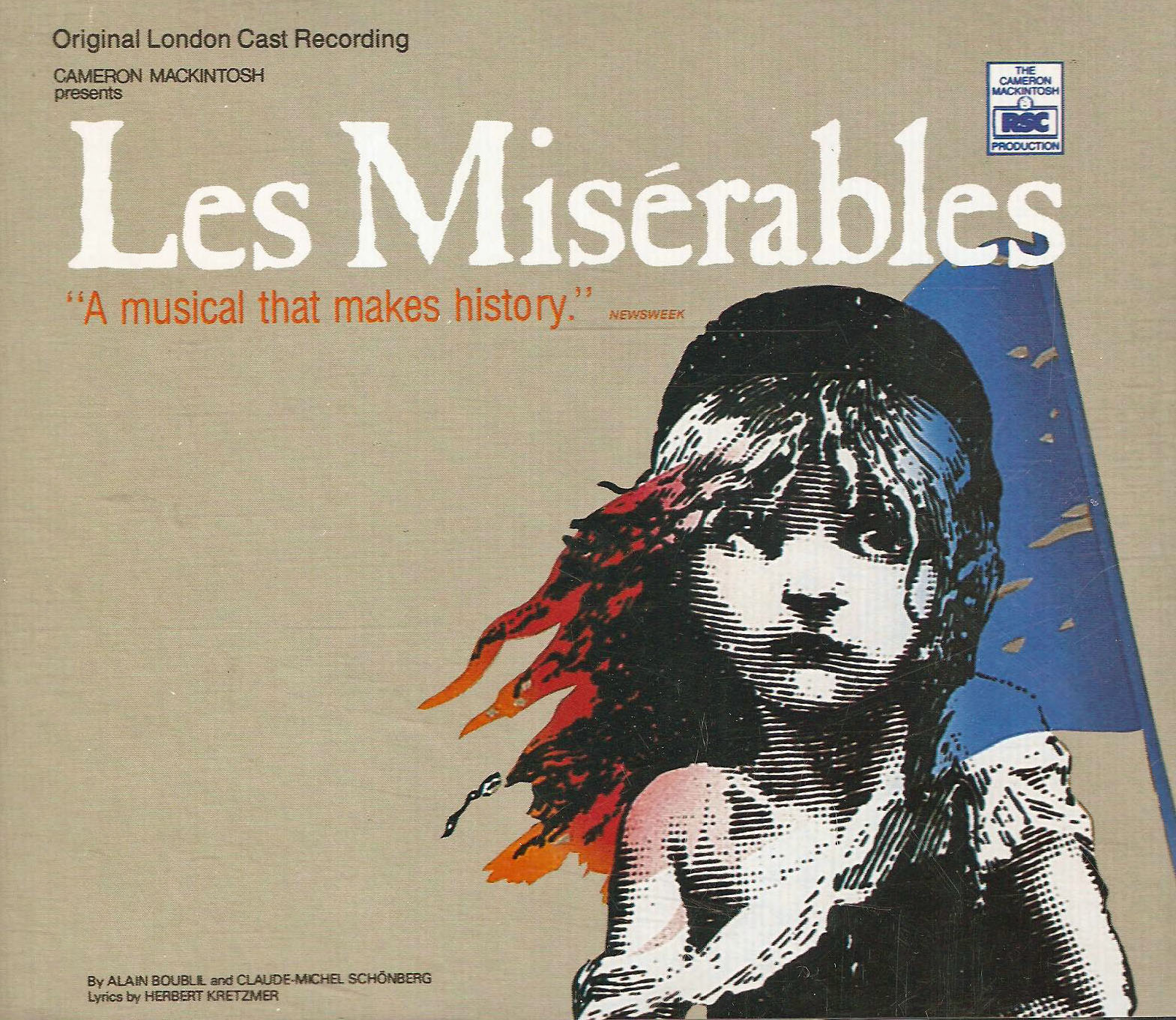

If you really want to understand the DNA of this show, don't just watch the Hugh Jackman movie. No offense to Hugh, but it’s a different vibe. To get close to the original magic, you need to track down the "Original London Cast Recording" (the one with the orange cover) and compare it to the "Complete Symphonic Recording."

You can hear the subtle shifts in how the characters were interpreted. You can hear where the actors breathed. You can hear the lack of digital pitch correction. It’s human.

Actionable Steps for Fans and Researchers:

- Listen to the 1980 Concept Album: If you can find the original French version (Version Originale Française), do it. It’s wild to hear "I Dreamed a Dream" as "J'avais rêvé d'une autre vie" with a 70s disco-pop beat.

- Track Down the Barbican Program: Collectors often sell original 1985 programs on eBay. They contain rehearsal notes and cast lists that show just how many people it takes to build a barricade.

- Watch the "Stage by Stage" Documentary: This is a 1985 documentary that actually shows the original cast in rehearsals. Seeing a young Michael Ball and a stressed-out Cameron Mackintosh is a masterclass in theater history.

- Check the Credits: Always look for the names Claude-Michel Schönberg and Alain Boublil. While the actors get the glory, the specific way they wrote for these specific voices is why the show works. They didn't write for a generic tenor; they wrote for Colm Wilkinson's range.

The legacy of the original cast for Les Miserables isn't just in the awards they won. It's in the fact that, forty years later, we still use them as the benchmark. Every time a new Valjean climbs those stairs or a new Fantine weeps over a locket, they are chasing the ghosts of 1985. It was a lightning-in-a-bottle moment that proved musical theater could be gritty, operatic, and commercially massive all at once.

You can't manufacture that kind of chemistry. You just have to put the right people in a room, give them a rotating floor, and hope for the best.