If you’ve ever walked into a gym, a dojo, or your grandmother’s spare bedroom, you know that smell. It’s heavy. It’s medicinal. It’s that sharp, cooling punch of camphor and menthol that clears your sinuses before it even touches your skin. We're talking about the origin of tiger balm, a story that doesn't actually involve any tigers, despite what the old playground rumors might have told you.

It’s actually a saga of survival.

Most people think of it as a generic drugstore staple, something you grab for a stiff neck or a mosquito bite. But the reality is much more interesting than a simple plastic tub. It’s a multi-generational business epic that started in the 1870s with a Chinese herbalist who was basically just trying to make life a little less painful for his neighbors.

The Kitchen Where It All Began

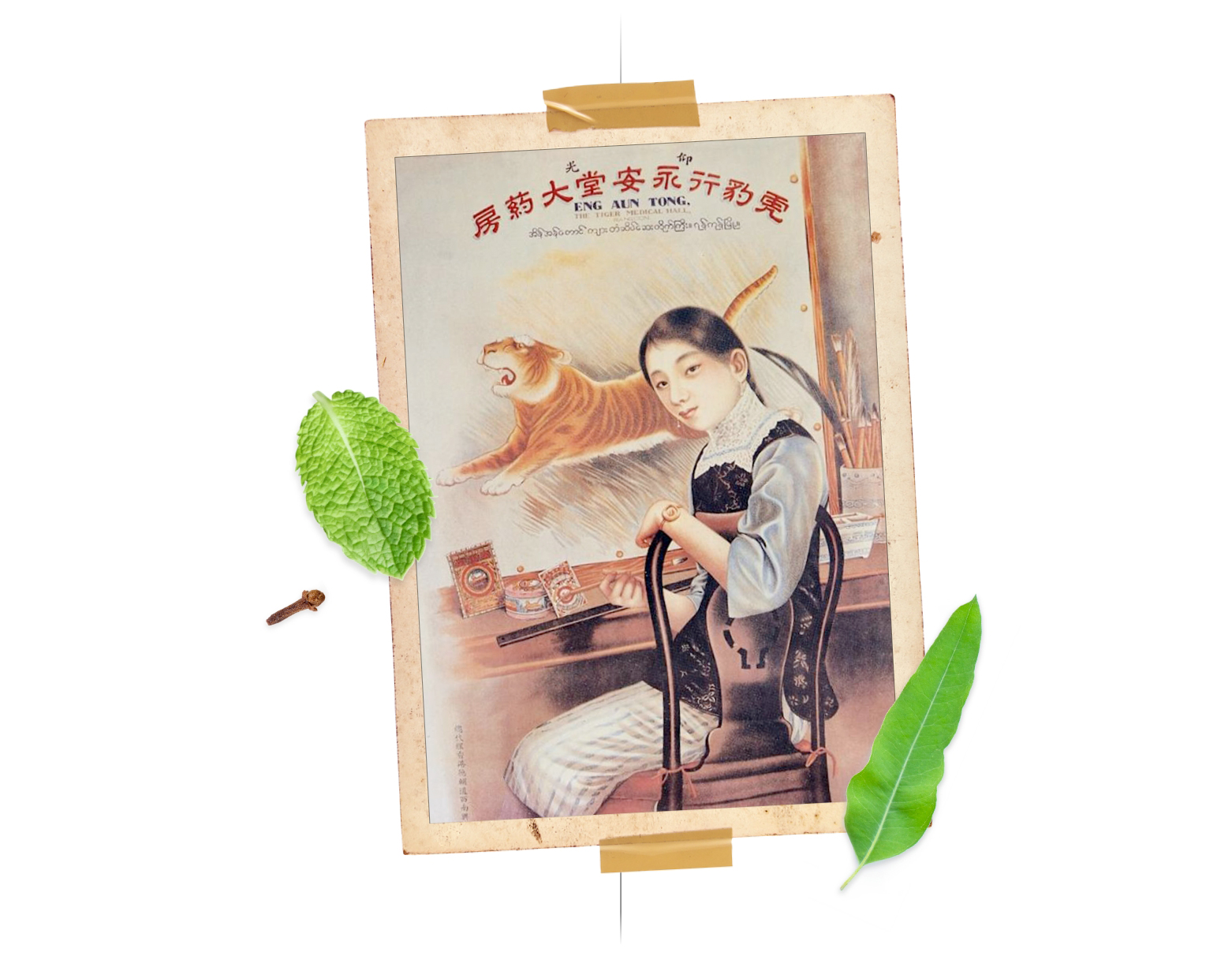

Aw Chu Kin was the man. He was an herbalist living in Rangoon (now Yangon), Myanmar, which was then under British colonial rule. He wasn't some corporate executive or a scientist in a lab; he worked in the Emperor’s court in China before migrating. He spent his days grinding herbs and experimenting with different oils to create a "Ban Kim Ee" or "Ten Thousand Golden Oils."

Basically, he wanted a catch-all.

The origin of tiger balm wasn't a "eureka" moment in a high-tech facility. It was a slow process of trial and error using things like cajuput oil, clove, and menthol. When Chu Kin died in 1908, he left the business to his two sons, Aw Boon Haw and Aw Boon Par. Their names literally translate to "Gentle Tiger" and "Gentle Leopard."

That’s where the name comes from.

It wasn't because there were tiger bones in the paste. It was branding. Boon Haw was the marketing genius of the family. He realized that "Ten Thousand Golden Oils" was a bit of a mouthful for the average person. He renamed it Tiger Balm after himself, and honestly, it’s one of the smartest branding moves in history. Who wants a "leopard" balm when you can have the strength of a tiger?

✨ Don't miss: Bed and Breakfast Wedding Venues: Why Smaller Might Actually Be Better

From Rangoon to Singapore: Scaling a Legend

The brothers didn't stay in Burma. They moved the operation to Singapore in the 1920s, and that’s when things got wild.

Boon Haw was basically the P.T. Barnum of Southeast Asia. He drove around in a custom car that was literally shaped like a tiger’s head, complete with headlights for eyes and a horn that roared. You couldn't miss him. This wasn't just about selling a topical ointment; it was about creating a lifestyle. He built "Tiger Balm Gardens" (now Haw Par Villa) in Singapore and Hong Kong, which are these bizarre, surrealist theme parks filled with statues illustrating Chinese folklore and the "Ten Stages of Hell."

He wanted the brand to be inescapable.

While the marketing was flashy, the formula remained surprisingly consistent. The origin of tiger balm is rooted in the "heat-clearing" principles of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). It’s designed to improve blood flow—the "Qi"—to the area where it's applied.

- Menthol and camphor act as counter-irritants.

- They trick your brain.

- You feel cold, then you feel hot.

- Your brain gets distracted from the deep ache in your muscle because it's too busy processing the intense sensation on the surface of your skin.

The Science of the "Sting"

We should probably talk about why it actually works, because it’s not just placebo or "ancient magic."

The ingredients in the original formula—the white and red versions—rely heavily on methyl salicylate (in some versions) and cajuput oil. Cajuput is a relative of the tea tree, and it’s a natural antiseptic and analgesic. When you rub it in, you’re causing vasodilation. That’s a fancy way of saying your blood vessels open up.

Interestingly, there’s a big difference between the Red and White versions that many people miss. The origin of tiger balm red includes cinnamon oil. That’s what gives it that deep, warming sensation. It’s better for deep muscle aches. The white version is heavy on the menthol and cajuput, making it cooler and better for headaches or stuffy noses.

🔗 Read more: Virgo Love Horoscope for Today and Tomorrow: Why You Need to Stop Fixing People

Don't put the red one on your face. Seriously. You’ll regret it within about thirty seconds.

Navigating the Myths and Misconceptions

One of the biggest hurdles the brand faced during the mid-20th century was the rumor about tiger parts. Because the name was so effective, people genuinely believed it contained ground-up tiger bone, which was a common (and devastating) ingredient in some ancient medicinal practices.

The company had to spend decades clarifying that no tigers are harmed.

It is entirely vegan. It’s wax-based, usually using paraffin or beeswax, which keeps the oils stable so they don't just evaporate the second you open the jar. This stability was crucial for the origin of tiger balm as a global product. In the early 1900s, most medicinal oils were liquids that leaked in your bag or spoiled in the heat. Making it a salve changed everything.

Why It Still Dominates the Market Today

It’s rare for a product to look almost exactly the same as it did 100 years ago and still be a top seller. Think about it. We have advanced lidocaine patches, NSAID gels, and high-tech vibrating massage guns. Yet, Tiger Balm is still in everyone’s medicine cabinet.

Part of it is nostalgia, sure. But mostly, it’s because the cost-to-efficacy ratio is through the roof.

It’s cheap. It lasts forever. It works.

💡 You might also like: Lo que nadie te dice sobre la moda verano 2025 mujer y por qué tu armario va a cambiar por completo

The Aw family eventually saw the business go public and go through various corporate restructurings, but the core identity never shifted. Haw Par Corporation now manages the brand, and they've expanded into patches, neck rubs, and even sprays. But the little hexagonal glass jar is still the icon.

How to Use It Like a Pro

If you really want to get the most out of it, stop just slapping it on.

- The Layering Trick: Apply a thin layer of the Red balm to a sore muscle. Don't rub it all the way in yet. Let it sit for a minute. Then, use a firm, circular motion to massage it deep into the tissue. The friction creates more heat, which activates the cinnamon and camphor more intensely.

- The Headache Hack: Use the White balm. Put a tiny—and I mean tiny—amount on your temples. Keep it far away from your eyes. The cooling effect helps constrict the blood vessels in your head, which can take the edge off a tension headache.

- The Pre-Workout Prep: Some athletes use it before they train. It "wakes up" the muscles and increases local circulation. Just be careful about the "heat" if you're going to be sweating a lot, as sweat can make the sensation feel significantly more intense.

Real World Cautionary Tales

Look, it’s safe, but it’s powerful.

I once knew a guy who applied the Red balm liberally to his lower back and then hopped into a hot shower. Don't do that. The hot water opens your pores and the "warming" effect of the cinnamon oil turns into a "burning" effect that feels like you've been dropped into a volcano.

Also, wash your hands. Twice. If you touch your eyes or any other sensitive bits after handling Tiger Balm, you’re going to have a very long, very uncomfortable afternoon.

Actionable Next Steps for Better Recovery

If you're dealing with chronic pain or just occasional stiffness, understanding the origin of tiger balm helps you appreciate why it’s a tool and not just a lotion.

- Identify your pain type: Use "White" for sharp, surface-level pain, congestion, or itching. Use "Red" for deep, throbbing muscle aches and joint stiffness.

- Check the ingredients: If you have sensitive skin, test a small patch first. The high concentration of essential oils can be irritating for some people.

- Storage matters: Keep the lid tight. The active ingredients are volatile oils. If you leave the jar open, the "magic" literally evaporates into the air, leaving you with a jar of useless wax.

- Beyond the rub: If you find the scent too strong for the office, look for the "Ultra" or "Soft" versions which are formulated to be slightly more discreet while maintaining the same active profile.

The legacy of Aw Chu Kin lives on because he solved a basic human problem: we all hurt sometimes. Whether you’re a pro athlete or someone who sat at a desk too long today, that little jar of history is still one of the most reliable ways to find a bit of relief. Just remember—no tigers, just a lot of very smart botany.