You've probably heard the story. It’s the one everyone tells at dinner parties or on playground benches to sound a little bit edgy. You know, the "fact" that the origin of Ring Around the Rosie nursery rhyme is actually a gruesome recount of the Black Death. People say the "rosie" is the rash, the "posies" were herbs to mask the smell of rotting bodies, and "ashes, ashes" refers to cremation.

It’s a great story. Honestly, it’s a perfect urban legend. But here’s the thing: it’s almost certainly complete nonsense.

Historical experts and folklorists have been trying to debunk the Great Plague connection for decades, yet the myth is stickier than a toddler’s hands. Why? Because we love the idea that something innocent hides a dark, macabre secret. But if we actually look at the timeline, the linguistic shifts, and the way children play, the real story of this rhyme is much more about Victorian social habits than medieval mass graves.

Why the Plague Theory Doesn't Hold Water

The Black Death ravaged Europe in 1347. The Great Plague of London happened in 1665. If the origin of Ring Around the Rosie nursery rhyme was actually a contemporary observation of these events, you'd expect to find some record of it from that time.

You won't.

There is zero evidence of the rhyme existing before the mid-19th century. Think about that for a second. We’re talking about a gap of nearly 200 years. If people were singing this while hauling bodies to pits, they somehow forgot to write it down, mention it in a diary, or include it in any collection of folk songs for two centuries. The first printed version doesn't appear until 1881 in Kate Greenaway’s Mother Goose.

Even then, the lyrics were different.

Folklore scholar Iona Opie, who spent her life documenting the secret history of children’s games, pointed out that the symptoms described in the rhyme don't even match the plague. The "rosie" rash? Plague buboes were black, purple, or puss-filled swellings in the groin and armpits, not cute little pink rings. The "sneezing" (often substituted for "ashes") wasn't a primary symptom of the bubonic plague either. It just doesn't fit.

🔗 Read more: Monroe Central High School Ohio: What Local Families Actually Need to Know

The Evolution of the Lyrics

One of the funniest things about the origin of Ring Around the Rosie nursery rhyme is that the "ashes, ashes" part—which people claim refers to burning bodies—is a relatively recent American addition.

If you go to Great Britain, kids don't say "ashes, ashes." They usually say "A-tishoo! A-tishoo!" mimicking a sneeze. In some 19th-century versions, the lyrics were:

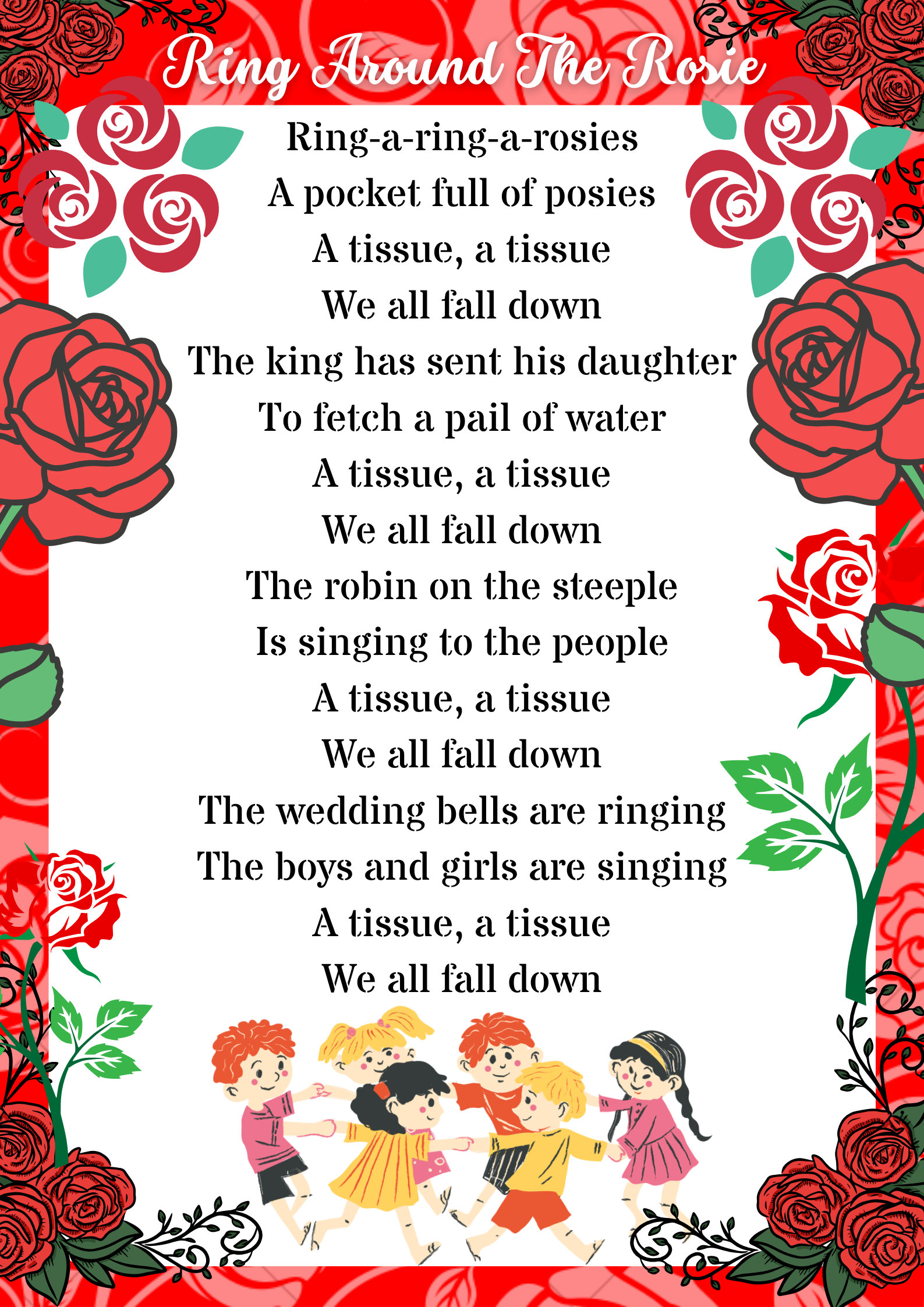

Ring-a-ring-a-roses,

A pocket full of posies,

One for Jack, and one for Jim,

And one for little Moses.

A-tishoo! A-tishoo! We all fall down.

Wait, little Moses? If this was about the plague, why are we bringing Moses into it?

The truth is that nursery rhymes are fluid. They change based on what sounds good or what’s funny to a five-year-old. The American "ashes" likely evolved from the German "Hushas," or was simply a phonetic corruption of the sneezing sound. It wasn't a commentary on the 1665 London fires or cremation practices. In fact, during the Great Plague, victims were buried in mass pits, not cremated. Cremation wasn't a standard practice in England during those outbreaks for religious reasons.

So, What Is the Real Story?

If it's not the plague, what is it? Basically, it’s a "sneezing game."

In the late 1800s, many religious groups (like the Quakers or certain Baptist sects) banned dancing. They thought it was sinful. But kids being kids, they found a loophole: "play-parties." These were games where you moved in a circle and sang, but because there was no "music" (instruments) and you were "playing" rather than "dancing," it was technically allowed.

💡 You might also like: What Does a Stoner Mean? Why the Answer Is Changing in 2026

The origin of Ring Around the Rosie nursery rhyme likely lies in these Victorian circle games. The goal was simple: move in a circle, perform a silly action (sneezing or curtsying), and then everyone falls down. The "falling down" was the punchline. It’s the same physical comedy that makes "London Bridge is Falling Down" or "Duck Duck Goose" popular. It’s about the sudden, chaotic end to a repetitive motion.

The "posies" weren't to ward off the "miasma" of disease. In the 1800s, carrying flowers or wearing them was just a common part of May Day festivals and courting rituals.

The Power of the Macabre Myth

So why does the plague theory persist? James Brunvand, a famous researcher of urban legends, notes that we have a psychological need to attach deep, dark meanings to simple things. It makes us feel "in the know."

When someone says, "Did you know that's actually about dead bodies?" they are asserting a kind of intellectual dominance over the "naive" version of the rhyme. It’s the same reason people think "Mary, Mary, Quite Contrary" is about Mary I of England torturing Protestants. (Spoiler: It’s probably just about a garden).

There's also the "Post-War Effect." The plague interpretation didn't actually become popular until after World War II. After the horrors of the Holocaust and the Blitz, society was primed to see death and destruction in everything, even in the nursery. It was during the late 1940s and 50s that the plague explanation started appearing in newspapers and books as "fact."

Basically, we projected our own trauma onto a 19th-century children's game.

Regional Variations You Never Knew

If you travel around, the "true" version of the rhyme disappears. It’s a shapeshifter.

📖 Related: Am I Gay Buzzfeed Quizzes and the Quest for Identity Online

- In Germany: The version "Ringelreihen" involves sitting under an elderberry bush.

- In Italy: "Giro Giro Tondo" talks about a world falling down and a wolf eating a lamb.

- In Switzerland: It’s often about "falling into the grass."

None of these versions mention disease. Most focus on the physical act of turning and the eventual "crash" at the end. If the Black Death were the source, you’d expect a consistent "medical" thread across all European versions. You just don't find it.

Instead, you find references to flowers, birds, and simple rhythmic nonsense. It’s the linguistic equivalent of a fidget spinner. It doesn’t have to mean anything; it just has to be fun to do.

Why Accuracy Matters for History

It might seem harmless to believe the plague story. Who cares, right?

Well, historians like Peter and Iona Opie cared because when we invent meanings for folk traditions, we lose the actual history of how people lived. The origin of Ring Around the Rosie nursery rhyme tells us a lot about 19th-century play, the Victorian obsession with floral imagery, and how children’s games migrated across the Atlantic.

When we overwrite that with a fake plague story, we’re essentially deleting the real history of childhood to make room for a "cool" ghost story.

The next time you see a group of kids spinning in a circle until they get dizzy and collapse in the grass, don't think about 17th-century morgues. Think about the fact that for at least 150 years, children have found joy in the exact same simple, dizzying loop. That’s a much more interesting—and human—connection than a mass grave could ever be.

How to Evaluate Nursery Rhyme Origins Yourself

If you’re curious about other rhymes like "London Bridge" or "Humpty Dumpty," keep these tips in mind to avoid falling for "folk etymology":

- Check the Date: If the rhyme supposedly refers to an event in 1500 but wasn't written down until 1850, be very skeptical.

- Look for Multiple Versions: Does the rhyme stay the same in other languages? If the "dark" part only exists in the American version, it’s probably a later addition.

- Consult Real Folklorists: Look for names like Iona Opie, Peter Opie, or the American Folklore Society. They spend their lives digging through archives to find the first recorded instances of these songs.

- Consider the Gameplay: Most nursery rhymes are tied to a physical action (bouncing on a knee, clapping, or spinning). The lyrics often serve the rhythm of the game, not the other way around.

The reality of history is often less "spooky" than the myths, but it's far more grounded in how our ancestors actually lived, played, and survived. The "Rosie" isn't a rash—it's just a flower. And sometimes, a sneeze is just a sneeze.