Let’s be honest. Accounting is basically a foreign language that nobody actually wants to learn until they’re staring at a spreadsheet at 2:00 AM wondering why their balance sheet looks like a crime scene. Most people hear "debit" and "credit" and think of their bank account. That’s the first mistake. If you’re trying to run a business or pass a CPA exam, you have to unlearn everything your banking app taught you.

It’s confusing. I get it.

When the bank says they "credited" your account, you see more money. In the world of double-entry bookkeeping, a credit could mean you have less money, more debt, or more revenue. It depends entirely on what you’re looking at. This debit and credit cheat sheet is going to strip away the academic fluff and give you the mechanical reality of how money moves through a ledger.

Why Your Brain Struggles With This

The term "debit" comes from the Latin debere, meaning "to owe." "Credit" comes from credere, meaning "to entrust." Back in the day of Luca Pacioli—the 15th-century friar who basically invented this system—these terms made perfect sense in a specific context of social obligation. Fast forward 500 years and we’re using the same words to track SaaS subscriptions and crypto trades.

The biggest hurdle is the "left and right" rule.

Forget "good and bad." Forget "plus and minus." In accounting, debit means left and credit means right. Period. Every single transaction you make has to touch at least two accounts. If you buy a new laptop for your office for $1,200, one account goes up and another goes down (usually). The total amount on the left must always, without exception, equal the total amount on the right. If they don't, you’ve messed up.

The Core Framework: DEALER

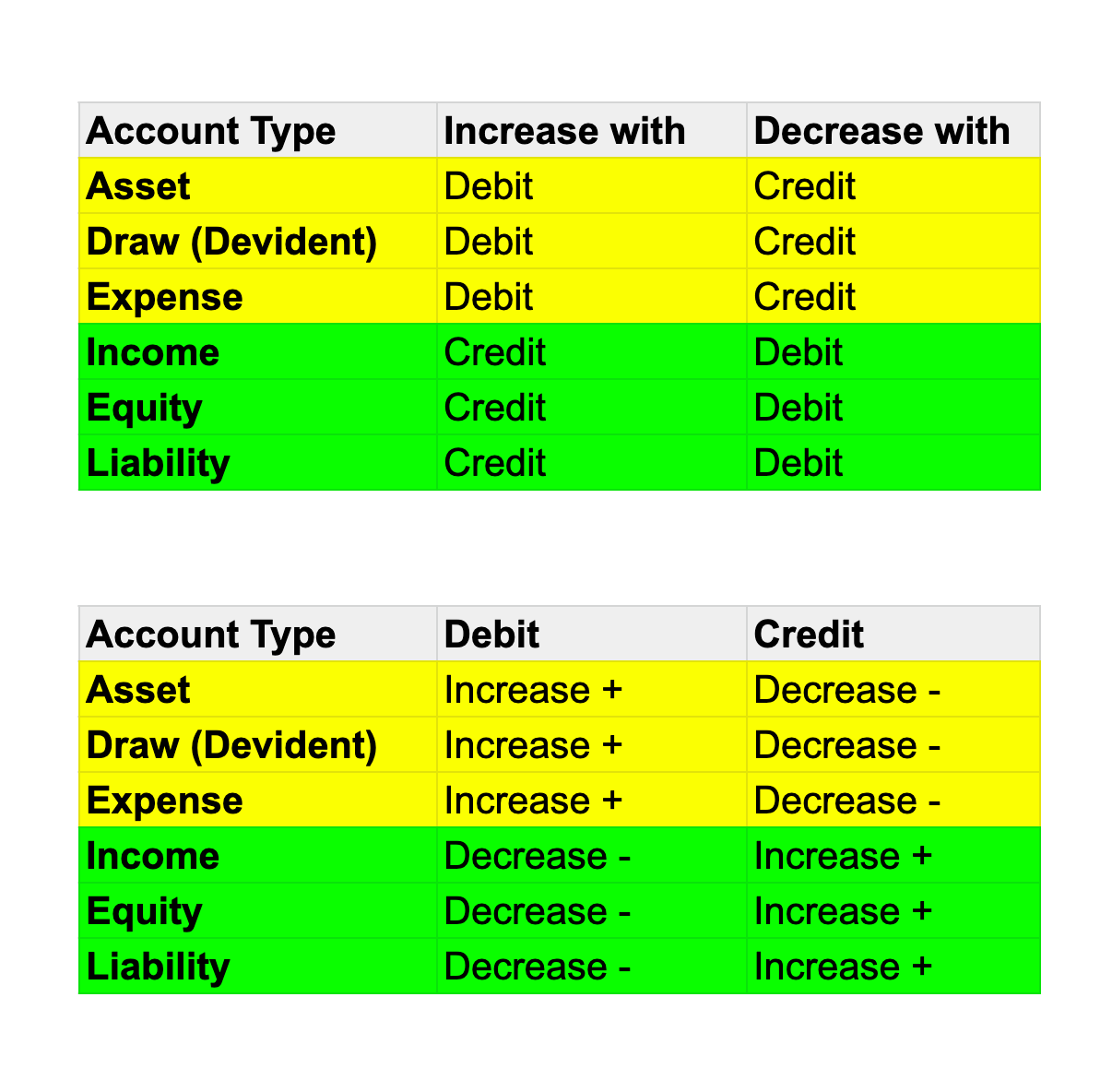

If you want a debit and credit cheat sheet you can actually memorize, use the DEALER acronym. It’s the industry standard for a reason. It splits all your accounts into two groups.

The first group is DEA: Dividends, Expenses, and Assets. For these three, a debit increases the balance. If you buy a building (Asset), you debit that account. If you pay your rent (Expense), you debit that account.

The second group is LER: Liabilities, Equity, and Revenue. For these, a credit increases the balance. If you take out a loan (Liability), you credit that account. If you sell a product (Revenue), you credit that account.

It feels backwards, right?

You’d think making a sale is a "positive" thing, so it should be a debit. But it’s not. Revenue increases your equity, and equity increases on the right side. It’s just how the math was built.

The Asset Paradox

Let's look at Assets. This is usually where the bank-account-confusion ruins people. Your cash is an asset. When you spend cash to buy supplies, your "Cash" account decreases. Since Assets increase with a debit, they decrease with a credit. So, spending money involves a credit to your cash account.

Most people feel like a "credit" should mean more money. Nope. Not here.

The Liability Reality

Now look at Liabilities. These are things you owe. Credit cards, bank loans, accounts payable to vendors. Because these are on the "LER" side of the house, they increase with a credit. If you charge $500 to a business credit card, you credit the Liability account. You are literally adding to your debt by "crediting" it.

Real World Examples (Not the Textbook Stuff)

Let's say you’re running a small consulting firm. You just sent an invoice for $5,000 to a client. They haven't paid you yet, but you use accrual accounting.

You’re going to debit Accounts Receivable (an Asset) for $5,000.

You’re going to credit Service Revenue (Revenue) for $5,000.

Both sides increased. The Asset side (left) went up because someone owes you money. The Revenue side (right) went up because you earned it. The scale is balanced.

Two weeks later, the client pays. Now what?

You debit Cash for $5,000 because your bank balance (an Asset) is going up.

You credit Accounts Receivable for $5,000.

Why credit the AR? Because that asset—the "promise to pay"—no longer exists. It’s been converted to cash. You’re essentially "zeroing out" the IOUs.

📖 Related: Thomas Friedman: Why the Author of The World Is Flat is Still Making People Mad

What About Payroll?

Payroll is a nightmare for beginners. It’s usually a mix of several accounts. You have Salary Expense (an Expense), which you debit because expenses increase on the left. But then you have various credits: Cash (for the net pay leaving your bank), and various Payable accounts for taxes you’ve withheld but haven't sent to the government yet.

It’s a dance. A very specific, rigid dance.

The Impact of Errors

If you swap a debit for a credit, you don’t just miss the mark by the amount of the transaction. You miss it by double. If you accidentally debit an account for $1,000 when you should have credited it, your books will be off by $2,000.

This is why the debit and credit cheat sheet is so vital for the month-end close.

Most modern software like QuickBooks or Xero tries to hide this from you. They use "Spend Money" or "Receive Money" buttons. But the software is still doing the double-entry work in the background. If you don't understand the underlying mechanics, you won't know how to fix a "reconciliation error" when the software inevitably gets confused by a weird bank feed.

Nuance: Contra Accounts

Just when you think you have it, accounting throws a curveball: Contra accounts. These are accounts that behave the opposite of their category.

Take "Accumulated Depreciation." It’s technically an Asset account (it lives with the assets on the balance sheet), but it has a credit balance. It exists specifically to reduce the value of another asset. Or "Sales Returns." It’s a Revenue account, but it carries a debit balance because it reduces your total sales.

These aren't "mistakes" in the system. They are "adjustments" that allow you to keep the original numbers clean while showing the net reality.

Practical Steps to Master Your Ledger

Don't try to memorize every possible transaction. Instead, follow a mental checklist every time you enter data.

📖 Related: Why the Wicked for Good Logo Actually Works for Brand Strategy

- Identify the accounts. What is actually happening? Did cash move? Did a debt increase? Did you "use up" something like insurance or rent?

- Classify them. Is it an Asset, Liability, Equity, Revenue, or Expense?

- Check the direction. Is the account increasing or decreasing?

- Apply the DEALER rule. - Increase DEA? Debit.

- Decrease DEA? Credit.

- Increase LER? Credit.

- Decrease LER? Debit.

If you’re still stuck, look at the Balance Sheet Equation: Assets = Liabilities + Equity.

This equation is the literal foundation of the entire financial world. Everything on the left side (Assets) naturally wants to be a debit. Everything on the right side (Liabilities and Equity) naturally wants to be a credit. Expenses and Dividends are essentially "temporary" accounts that eventually get sucked into Equity at the end of the year, which is why they have their own specific rules during the month.

Actionable Setup for Your Business

Stop guessing. If you’re managing your own books, print out a small card that says:

LEFT: Debits (Assets, Expenses, Dividends)

RIGHT: Credits (Liabilities, Equity, Revenue)

Tape it to your monitor. When you’re looking at a transaction, ask: "Which side of the equation is this hitting?"

Next, perform a trial balance every single month. Don't wait for tax season. A trial balance is just a report that lists all your accounts and their balances. If the total of the debits doesn't equal the total of the credits, you have a "broken" ledger. Finding a $50 mistake in thirty transactions is easy. Finding it in three thousand transactions in April is a nightmare that will cost you thousands in accounting fees.

Invest in a basic "Chart of Accounts" review. Most business owners have too many categories. Keep it simple. The more complex your accounts, the more likely you are to flip a debit and credit. Clean books start with a clean structure. Once you have the DEALER logic down, the rest of accounting is just learning where the specific pieces of paper go.